As you fire up the grill this Labor Day and enjoy the last long weekend of summer, here’s a thought to go with your burger: where did your weekend actually come from?

It wasn’t a gift from a generous boss or a natural feature of the calendar. The American weekend, and the 40-hour workweek that defines it, was born from a brutal, decades-long constitutional battle that went all the way to the Supreme Court.

This is the surprising, patriotic, and often-forgotten story of how our legal system gave us the time to rest, recharge, and enjoy our lives. It’s a tale of overworked bakers, stubborn judges, and a president who changed the course of American history.

Test Your Labor Day Knowledge With Our

Special Edition Labor Day Trivia

Play HERE

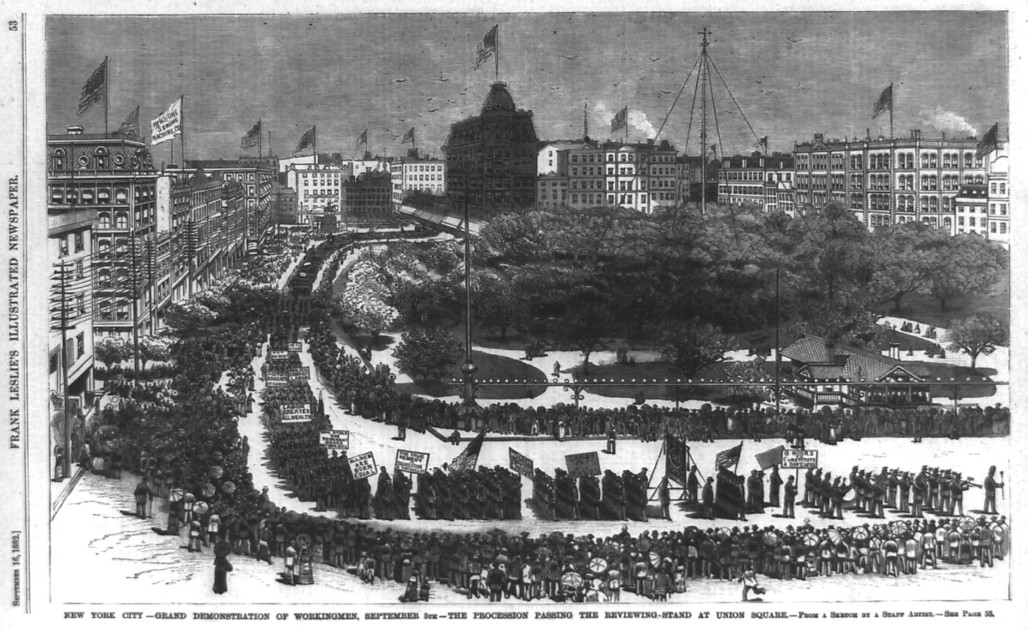

The Gilded Age Grind

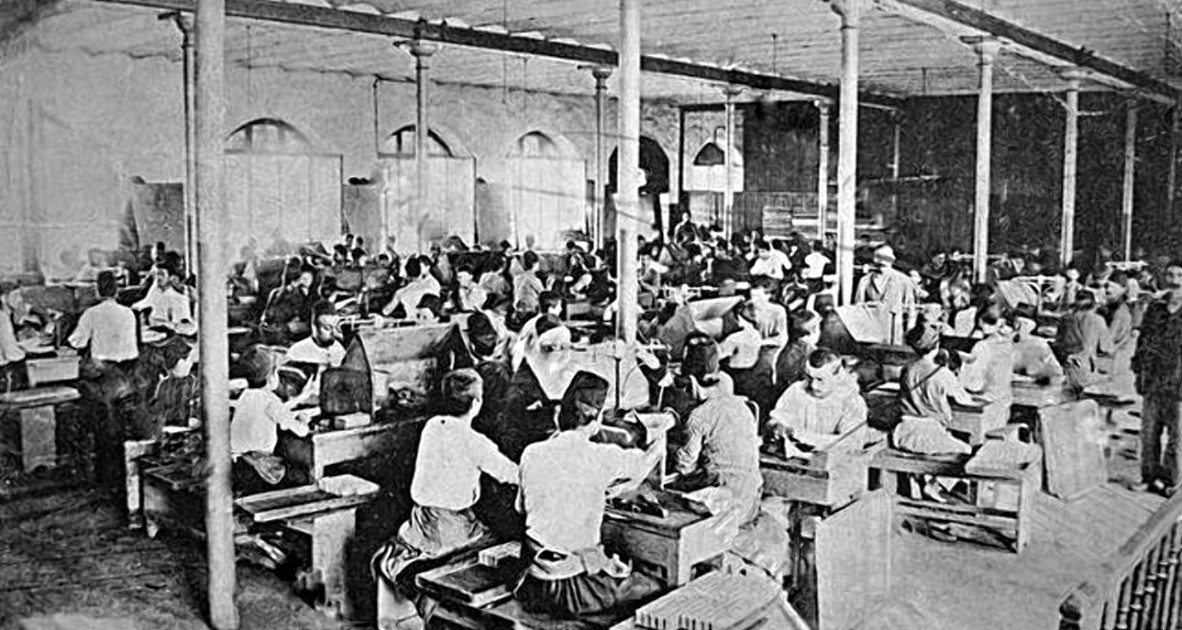

It’s hard to imagine today, but for most of our history, the concept of a “weekend” didn’t exist for the average worker. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the industrial grind was relentless: 10 to 12-hour workdays were common, and a six or even seven-day workweek was the norm for millions of Americans in factories, mines, and mills.

As the labor movement grew, states began to pass laws to protect workers, setting limits on work hours and establishing a minimum wage. But these new laws ran into a powerful and unexpected roadblock: the Supreme Court of the United States.

The Supreme Court Says “No”

In a series of cases during a period now known as the “Lochner Era,” the Supreme Court repeatedly struck down these labor protections. The Court’s reasoning was based on a constitutional theory called “liberty of contract.”

The justices believed that the Fourteenth Amendment protected a fundamental right for an employer and an employee to make any contract they wanted, and that the government had no business interfering. In the most famous case, Lochner v. New York (1905), the Court struck down a New York law that limited bakers to a 10-hour day and a 60-hour week. The Court essentially ruled that if a baker wanted to agree to work 80 hours a week, that was his liberty, and the Constitution protected it.

The “Switch in Time that Saved Nine”

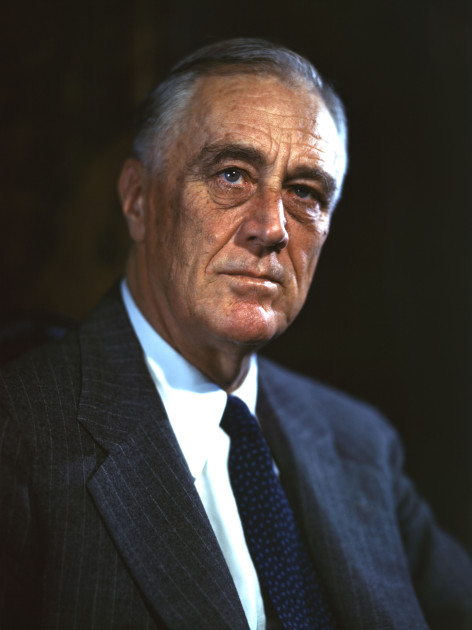

For decades, the Court’s “liberty of contract” doctrine stood as a great wall against labor reform. But everything changed with the Great Depression and the New Deal of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. After the Court struck down several of his key economic programs, a frustrated FDR proposed his famous “court-packing plan” to add new justices to the bench.

Facing this immense political pressure, the Court made a stunning reversal. In the 1937 case West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish, the Court, in a 5-4 decision, upheld a state minimum wage law, effectively killing the Lochner-era doctrine. This famous reversal is often called “the switch in time that saved nine,” as it is believed that one justice’s change of heart saved the Court from FDR’s political interference.

The Birth of the Modern Weekend

That single court decision opened the floodgates. With the constitutional path finally clear, Congress, using its power to regulate interstate commerce, was able to pass one of the most important pieces of legislation in American history: the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938.

This is the law that established the eight-hour day and the 40-hour workweek, created the right to overtime pay, and set a national minimum wage. It is the law that, for millions of Americans, created the modern weekend.

So as you enjoy this Labor Day, it’s worth remembering the long and difficult constitutional journey it took to get here. Your weekend is a testament to the fact that our Constitution is not a static document, but a living one, capable of evolving to meet the needs of its people. It’s a reminder that even our most basic comforts were once the subject of a great American legal battle – and that is a story worth celebrating.