Nick Reiner, son of acclaimed director Rob Reiner, was arrested Sunday night on suspicion of murdering his parents. The 32-year-old is being held without bail after Rob and Michele Reiner were found dead with stab wounds in their Brentwood home.

The arrest came five hours after firefighters discovered the bodies. Nick wasn’t at the scene – police located him near USC’s campus and took him into custody around 9:15 p.m. He was scheduled to appear in court Tuesday, but his attorney said he wasn’t “medically cleared” to be transported.

The case has every element that turns a tragedy into a media spectacle: Hollywood royalty, alleged family violence, a history of addiction and rehab struggles, and witnesses claiming the suspect acted strangely at a celebrity Christmas party the night before. But beneath the tabloid angles sits a constitutional framework that will determine how this case unfolds – one that protects even accused murderers from government overreach while giving prosecutors enormous power to pursue charges.

The question isn’t whether Nick Reiner deserves those protections. It’s whether they’ll actually constrain the process or just provide procedural cover for an outcome everyone already expects.

What Due Process Guarantees in Murder Cases

The Fifth Amendment requires that no person “be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right to a speedy and public trial, an impartial jury, and the assistance of counsel.

Those protections apply regardless of how heinous the alleged crime or how famous the victims. They’re not conditional on whether the suspect seems guilty or whether public outrage demands swift justice. They’re structural requirements designed to prevent the government from railroading defendants through a criminal justice system that has every incentive to secure convictions.

Nick Reiner gets a lawyer – he’s already hired Alan Jackson, the high-profile attorney who represented Karen Read. He gets a presumption of innocence until the prosecution proves guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. He gets discovery of the evidence against him. He gets the right to confront witnesses and present a defense.

But those rights exist within a system where prosecutors control charging decisions, judges control bail determinations, and juries make credibility judgments about competing narratives. Due process guarantees the procedures will be followed. It doesn’t guarantee the procedures will produce accurate results.

The Bail Question and Pretrial Detention

Nick Reiner is being held without bail. That means he’ll remain in custody throughout the pretrial process unless a judge decides he’s not a flight risk or a danger to the community.

The Eighth Amendment prohibits “excessive bail,” which implies there’s a right to reasonable bail in most cases. But California law allows judges to deny bail entirely in capital cases or cases where the prosecution seeks life without parole. If prosecutors charge Nick with special circumstances murder – which can include murder for financial gain, murder involving torture, or multiple murders – they can argue he should be held without bail as a matter of law.

The constitutional question is whether pretrial detention violates due process when the defendant hasn’t been convicted yet. The Supreme Court has held that pretrial detention is permissible if it’s based on dangerousness and flight risk, not punishment. But the practical reality is that defendants held without bail face enormous pressure to accept plea deals rather than wait months or years in custody for trial.

That pressure exists regardless of guilt or innocence. If you’re innocent but can’t make bail, you might plead guilty to a lesser charge just to get a sentence that lets you go home sooner than trial would. If you’re guilty but have a weak case against you, pretrial detention gives prosecutors leverage to extract a plea rather than risk acquittal at trial.

The Eighth Amendment protects against excessive bail. It doesn’t protect against the coercive effects of any detention on a defendant’s strategic calculations about whether to fight charges or take a deal.

The Insanity Defense That Probably Won’t Work

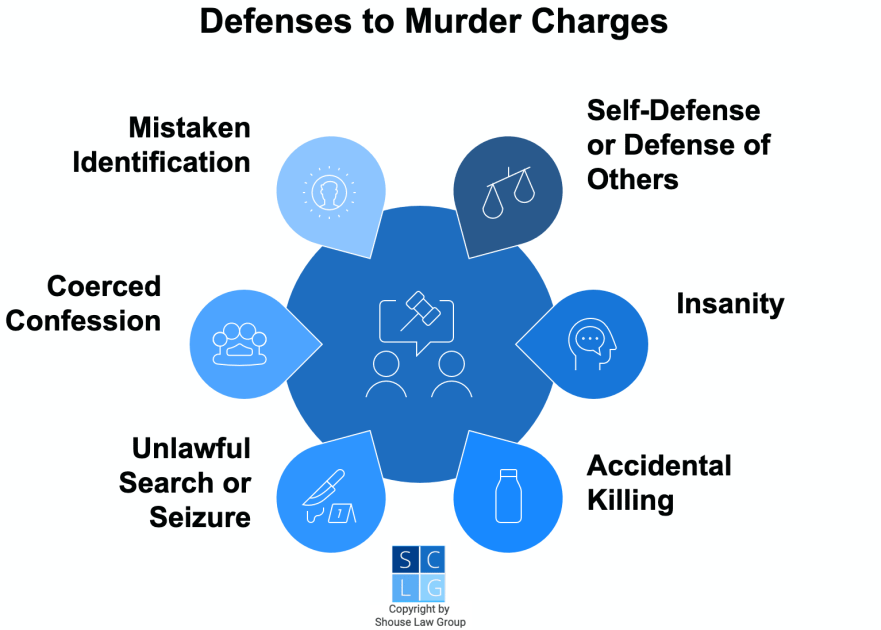

Legal experts are already discussing whether Nick’s defense might pursue an insanity plea. California law allows a not guilty by reason of insanity verdict if the defendant couldn’t understand the nature of their act or distinguish right from wrong due to mental disease or defect.

The standard is incredibly high. You can’t just be mentally ill. You have to be so impaired that you literally don’t know you’re committing a crime. Schizophrenia that makes you think your parents are aliens trying to harm you might qualify. Depression and drug addiction don’t.

Reports indicate Nick got into an argument with his parents at a Christmas party the night before they were found dead. Legal experts point out that having a coherent disagreement with someone – understanding what you’re arguing about and why you’re angry – is inconsistent with the level of psychosis required for an insanity defense.

If you’re capable of having an argument, you understand who you’re talking to and what’s happening. That’s the opposite of the delusional state insanity requires. The constitutional protection here is minimal – states can set their own insanity standards, and California’s is narrow by design.

Nick’s attorney could still pursue a psychiatric evaluation and raise mental health issues at sentencing if he’s convicted. But an outright insanity acquittal based on the reported facts would require proving a level of detachment from reality that seems inconsistent with the alleged premeditation.

Premeditation and the Degrees of Murder

California divides murder into degrees based on premeditation and special circumstances. First-degree murder requires proof that the killing was willful, deliberate, and premeditated. Second-degree murder covers intentional killings without that level of advance planning.

The distinction matters enormously for sentencing. First-degree murder can carry life without parole. Second-degree typically allows for eventual parole eligibility.

Prosecutors are reportedly focusing on Nick’s alleged argument with his parents Saturday night as evidence of premeditation. If he got into a fight, left the party, and returned the next day to kill them, that time gap demonstrates planning rather than a heat-of-passion reaction.

That theory faces constitutional scrutiny under the due process requirement that the government prove every element of the offense beyond a reasonable doubt. The defense will argue that an argument doesn’t prove premeditation – people fight with family members all the time without it leading to murder. Coming back the next day could just mean he was still angry, not that he planned the killing in advance.

But juries are allowed to draw inferences from circumstantial evidence. If Nick argued with his parents, left, wasn’t at the scene when their bodies were discovered, and was arrested hours later near a college campus, that pattern tells a story prosecutors can use to establish premeditation even without direct evidence of planning.

The Public Trial Right and Media Saturation

The Sixth Amendment guarantees a public trial, but it also guarantees an impartial jury. Those two rights can conflict in high-profile cases where media coverage makes it nearly impossible to find jurors who haven’t already formed opinions about guilt.

Rob Reiner was famous. His death is receiving extensive coverage. Details about Nick’s rehab history, his behavior at the Christmas party, and witness claims about what Michele allegedly said before dying in the ambulance are already public.

Defense attorneys can request a change of venue, arguing that pretrial publicity has poisoned the jury pool. But California courts generally deny those motions unless the defendant can show that extensive coverage has created a presumption of guilt that voir dire can’t cure. Courts assume jury instructions about presumption of innocence and reasonable doubt will overcome whatever jurors saw in the news.

That assumption is often wrong. Studies consistently show that pretrial publicity affects jury verdicts even when jurors say they can be impartial. But the constitutional protection is limited – you get a jury from the community where the crime occurred unless the publicity is so overwhelming that no fair trial is possible.

The Reiner case is getting attention, but it’s not approaching the saturation level of cases like O.J. Simpson or Casey Anthony. A change of venue motion will likely fail, and Nick will face a Los Angeles jury that’s heard about the case but hasn’t been completely consumed by it.

What Happens If the Evidence Is Weak

The reports so far describe circumstantial evidence: an argument the night before, Nick’s absence from the scene, his arrest near USC. If prosecutors have physical evidence – DNA, fingerprints, surveillance footage, witnesses who saw him at the house – they haven’t revealed it yet.

Due process requires the government to disclose exculpatory evidence to the defense. If there’s forensic evidence that contradicts the prosecution’s theory, or witnesses who place Nick elsewhere, prosecutors must turn it over. The Brady rule, established by the Supreme Court, makes it a due process violation to withhold evidence that’s favorable to the accused.

But Brady violations are hard to detect and harder to remedy. If prosecutors don’t disclose evidence and the defendant is convicted, you only find out about the violation later – often years later when appeals courts review the case. By that point, witnesses have disappeared, evidence has degraded, and the trial can’t be re-done with the complete record the defense should have had.

The constitutional protection exists on paper. In practice, it depends entirely on prosecutors’ willingness to comply and judges’ willingness to sanction violations when they’re discovered.

The Plea Bargain Shadow

Roughly 95% of criminal cases end in plea bargains rather than trials. That statistic holds even in murder cases, though the percentage is lower for high-profile defendants with resources to mount a defense.

Nick Reiner can afford Alan Jackson, which means he can fight the charges if he wants to. But the plea bargaining process will still shape every strategic decision his defense makes.

If prosecutors offer a deal – say, second-degree murder with parole eligibility after 20 years instead of first-degree murder with life without parole – Nick has to decide whether the risk of trial is worth the potential difference in outcome. That calculation happens under enormous pressure: he’s in custody, facing the possibility of dying in prison, making a decision about whether to accept a guaranteed bad outcome or gamble on a potentially worse one.

The Constitution doesn’t regulate plea bargaining beyond requiring that pleas be knowing and voluntary. Courts have held that prosecutors can threaten harsher charges to induce pleas, and that the vast disparity between trial sentences and plea offers doesn’t constitute unconstitutional coercion.

Due process guarantees Nick can’t be tortured into confessing or threatened into pleading guilty. It doesn’t protect him from the structural coercion built into a system where going to trial means risking exponentially worse consequences than taking a deal.

What the Constitution Doesn’t Protect Against

The constitutional framework surrounding criminal trials is designed to prevent specific abuses: coerced confessions, warrantless searches, denial of counsel, biased juries, insufficient evidence to convict.

It’s not designed to ensure accurate outcomes. Innocent people get convicted when juries believe prosecution witnesses over defense witnesses. Guilty people get acquitted when the evidence doesn’t meet the reasonable doubt standard. The process can be constitutionally sound and still produce wrong results.

Nick Reiner will get his day in court. He’ll get competent counsel and the right to present a defense. The prosecution will have to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Those protections matter – they prevent the worst abuses that criminal justice systems are capable of.

But they don’t prevent wrongful convictions based on circumstantial evidence and jury credibility determinations. They don’t stop prosecutors from overcharging to create plea pressure. They don’t eliminate the effects of pretrial detention on defendants’ strategic calculations.

The Constitution guarantees process, not justice. Whether Nick Reiner murdered his parents is a factual question that a jury will decide based on the evidence presented at trial – or that won’t reach a jury at all if he accepts a plea deal.

The constitutional protections he’s entitled to will shape how that decision gets made. But they won’t determine whether the outcome is correct. They’ll just ensure the procedures were followed while the system reached whatever conclusion it reaches.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Due Process

Rob and Michele Reiner are dead. Their son is accused of killing them. The public wants answers and accountability. The criminal justice system will provide both – a trial or a plea, a conviction or an acquittal, a sentence that either ends Nick’s life in prison or gives him a chance at eventual release.

The Constitution’s role in that process is narrower than most people assume. It prevents the government from using certain methods to secure convictions. It doesn’t prevent convictions based on weak evidence, emotional appeals, or jury mistakes.

Due process is a floor, not a ceiling. Nick Reiner gets a lawyer, a trial, and procedural protections. Whether those protections translate into a fair outcome depends on factors the Constitution doesn’t control: the quality of the evidence, the effectiveness of his attorney, the credibility judgments of twelve strangers, and the strategic decisions made under the enormous pressure of facing life in prison.

The Framers designed a system meant to prevent tyranny, not to guarantee accuracy. What happens to Nick Reiner will test whether that distinction matters when the stakes are this high and the public attention this intense.

The Constitution will guarantee him process. Whether that process produces justice is a different question entirely.