The pilgrims and Wampanoag shared a harvest meal in 1621. Nobody called it “Thanksgiving” for 220 years. The actual event was barely documented and quickly forgotten. The peace treaty they signed seven months earlier mattered far more historically – it lasted 50 years.

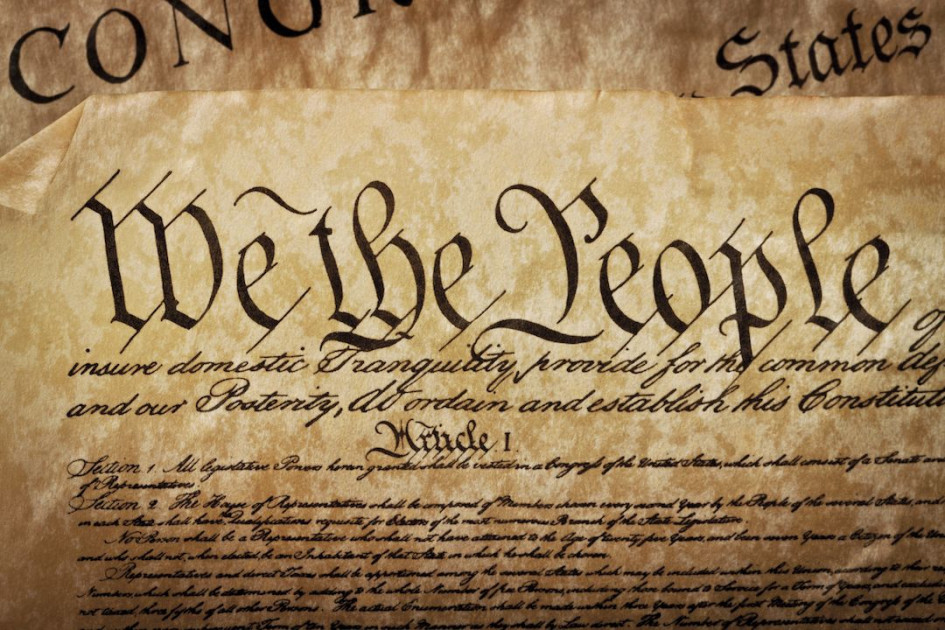

America’s Thanksgiving tradition didn’t come from Plymouth Rock in 1621. It came from George Washington in 1789, declaring gratitude not for a harvest but for the newly ratified Constitution and the end of the Revolutionary War.

The story most Americans learn in elementary school – pilgrims and Indians sharing turkey and establishing a tradition – is almost entirely mythology created centuries later. The real origin of Thanksgiving as a national holiday is a constitutional story, not a colonial one.

Here’s what actually happened, what we get wrong, and why it matters that Thanksgiving’s origin is about forming a republic rather than sharing a meal.

What Actually Happened In 1621 (And Why It Wasn’t “Thanksgiving”)

Edward Winslow, a Plymouth pilgrim, wrote a letter describing a harvest celebration in 1621. His account mentions that after the harvest, the governor sent four men hunting, and about 90 Wampanoag including their leader Massasoit joined them for three days of feasting.

That’s it. That’s the entire historical record of the “first Thanksgiving.” Winslow never called it Thanksgiving. The word appears nowhere in his letter.

In fact, among 17th-century pilgrims, “Thanksgiving” meant something completely different – a solemn period of prayer and fasting, not feasting. The 1621 event was just a routine English harvest celebration that happened to include Indigenous guests.

Nobody thought this meal was historically significant for over two centuries. It wasn’t mentioned in most colonial histories. It wasn’t celebrated annually. It was one harvest feast among many that happened throughout the colonies.

The term “first Thanksgiving” was invented in 1841 when publisher Alexander Young printed Winslow’s letter and added a footnote calling it the “first Thanksgiving.” The name stuck, and gradually the mythology built around it until it became the origin story Americans learn today.

The Context Nobody Teaches: Disease, Desperation, And Grave Robbing

The pilgrims arrived in Cape Cod in November 1620, six weeks before winter, with almost no food. They believed New England would be warmer than the Netherlands and southern England because it’s further south. They were catastrophically wrong.

In their desperation, the pilgrims robbed corn from Native American graves and storehouses soon after arriving. Despite that stolen food, half of them died during their first winter.

The only reason they had space to settle at Plymouth was that thousands of Wampanoag and other coastal Native Americans had died from European diseases in the years immediately before 1620. The pilgrims were literally settling on top of a cemetery.

“The pilgrims didn’t know it, but they were moving into a cemetery,” historian Charles Mann notes. Europeans who’d sailed to New England just a few years earlier found flourishing coastal communities. By 1620, disease had devastated those populations, leaving abandoned villages the pilgrims could occupy.

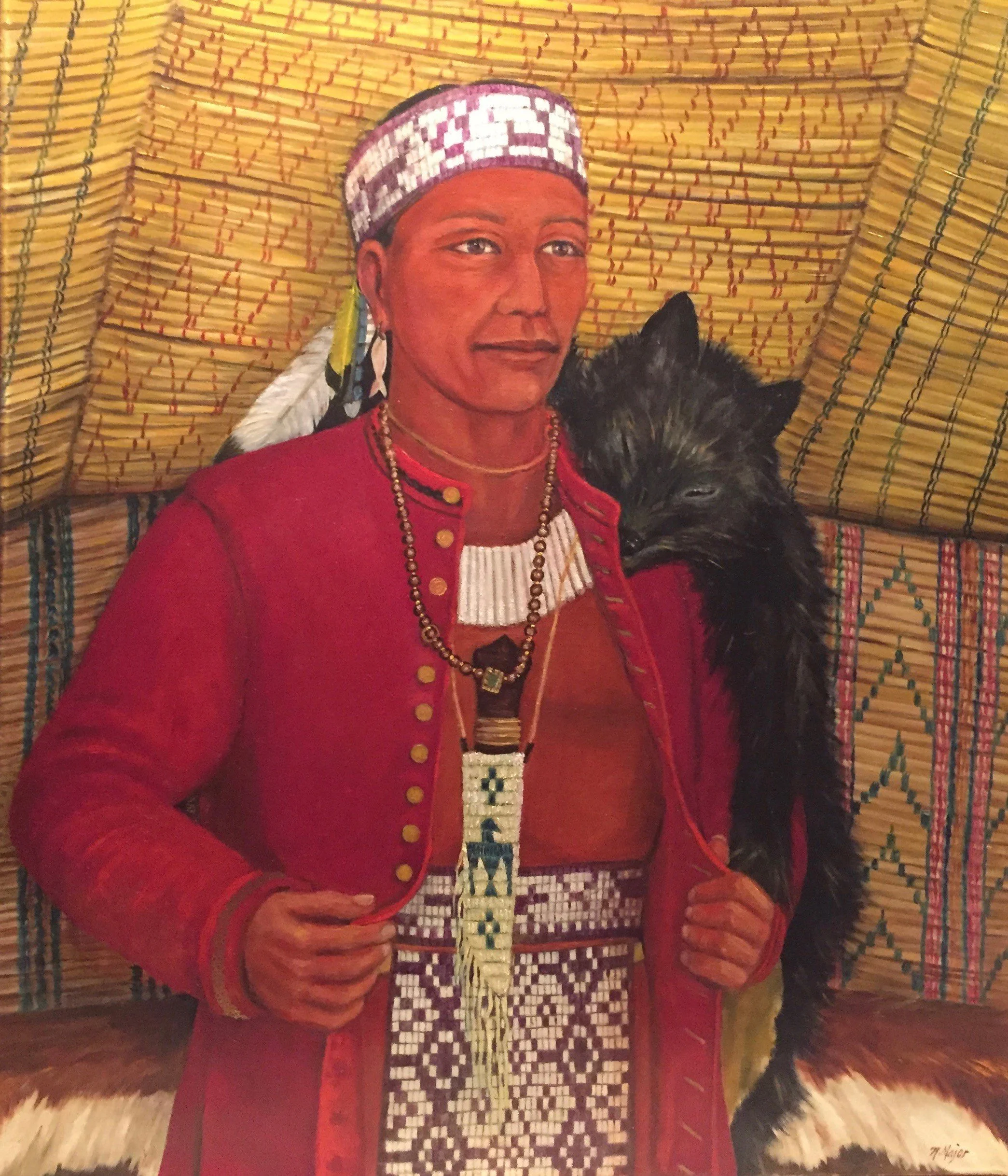

The 1621 harvest feast happened because Tisquantum (Squanto), an English-speaking Wampanoag, taught the surviving pilgrims how to farm sustainably. Without that help, there would have been no harvest to celebrate.

The Political Alliance That Actually Mattered

The real historically significant event wasn’t the 1621 meal – it was the peace treaty signed seven months earlier between the pilgrims and Massasoit’s Wampanoag confederation.

That treaty lasted 50 years. It was driven not by harmony or shared values, but by political calculation on both sides.

The Wampanoag had been weakened by disease and faced rivalry with the more powerful Narragansett tribe. An alliance with the English provided both trade access (the English traded valuable steel tools for beaver pelts the Wampanoag considered nearly worthless) and deterrence against rivals.

The pilgrims needed the alliance because they were vulnerable, unprepared, and surrounded by Indigenous nations who’d already driven away previous English attempts at settlement.

“It’s a little like somebody comes to your door, and says I’ll give you gold if you give me a rock,” historian Mann explains. The Wampanoag saw strategic advantage in the arrangement, not friendship.

This political treaty shaped New England history far more than one harvest meal. But treaties don’t make heartwarming elementary school pageants, so we remember the feast and forget the diplomacy.

When Washington Actually Created Thanksgiving (1789)

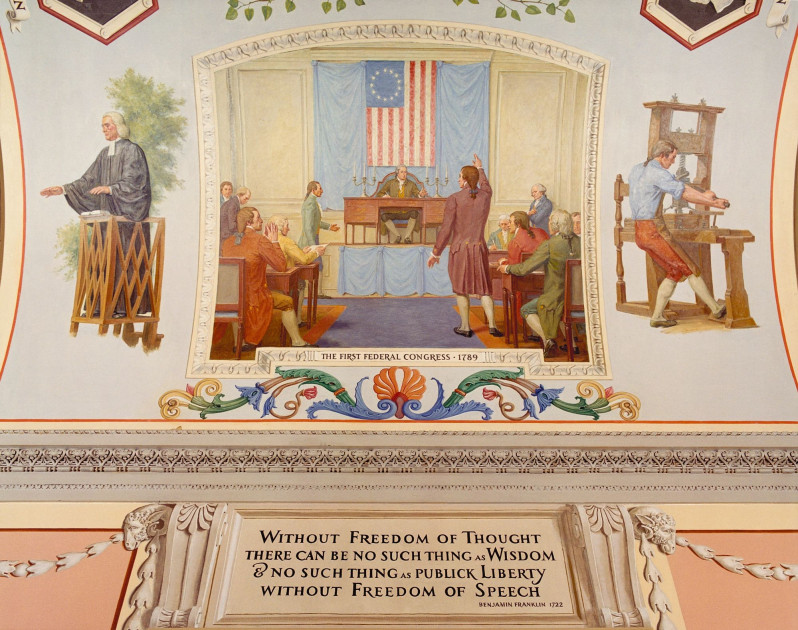

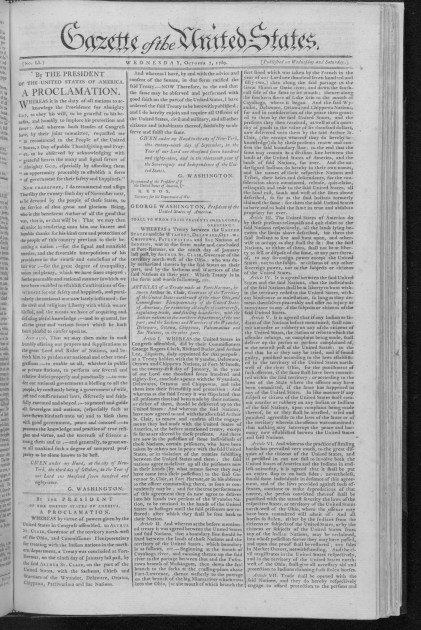

The first national Thanksgiving in American history occurred on November 26, 1789 – not because of pilgrims, but because Congress asked President Washington to declare a day of thanksgiving after ratifying the Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The Congressional resolution on September 25, 1789 came immediately after framing the Bill of Rights. Representative Elias Boudinot proposed “that a joint committee of both Houses be directed to wait upon the President of the United States to request that he would recommend to the people of the United States a Day of Public Thanksgiving and Prayer.”

Roger Sherman defended the resolution by citing “precedents in Holy Writ,” arguing the practice was “worthy of a Christian imitation on the present occasion.”

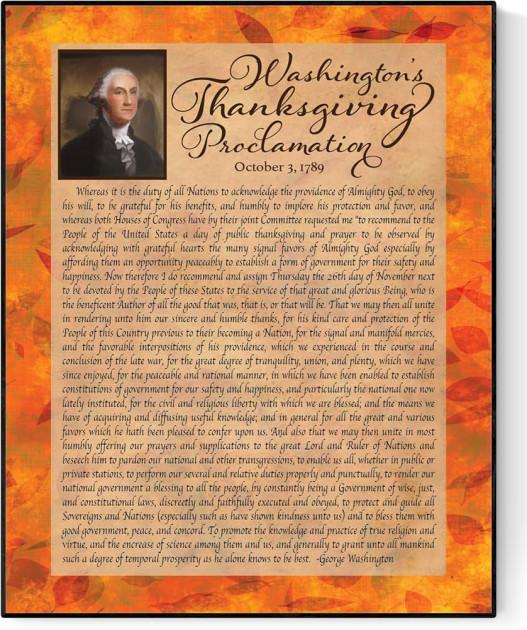

Washington’s October 3, 1789 proclamation established November 26 as a national day of thanks. His reasoning had nothing to do with pilgrims or harvests. He declared thanksgiving for:

- The end of the Revolutionary War

- Establishing “a form of government for their safety and happiness”

- The Constitution and Bill of Rights

- “Civil and religious liberty”

- Peace after years of conflict

This was constitutional thanksgiving, not colonial thanksgiving. Washington was celebrating that Americans had successfully created a republic, not that colonists once shared a meal.

What Washington Actually Said (And Why It Matters)

Washington’s proclamation is explicitly religious in ways that make modern constitutional scholars uncomfortable. He declared it was “the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits.”

He called for Americans to thank “that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be” for protection during the war, for enabling them to establish constitutional government, and for “civil and religious liberty.”

Then Washington asked Americans to pray that God would “pardon our national and other transgressions,” “render our national government a blessing to all the people,” and “promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue.”

This is the actual origin of Thanksgiving as a national holiday – a presidential proclamation explicitly grounded in religious thanksgiving for constitutional government and national survival after revolution.

Whether Washington’s overtly religious proclamation would be constitutional today under modern Establishment Clause interpretation is debatable. But in 1789, neither Washington nor Congress saw any tension between religious proclamation and constitutional governance.

The Sporadic Tradition Before Lincoln

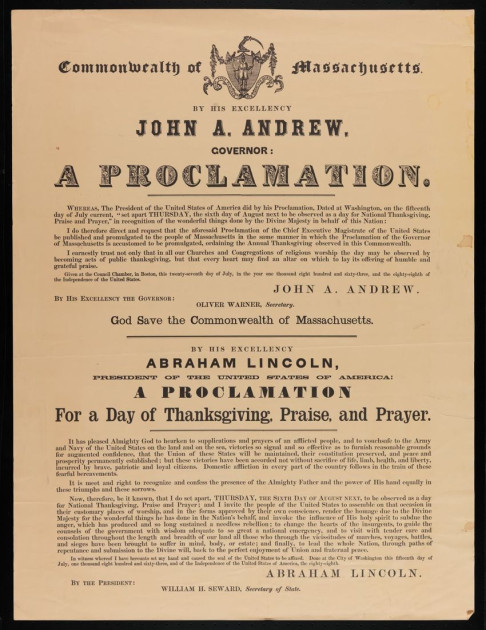

After Washington’s 1789 proclamation, national Thanksgiving declarations occurred only occasionally. Washington issued another in 1795. John Adams issued them in 1798 and 1799. James Madison issued them in 1814 and 1815 after the War of 1812.

Most Thanksgiving observances during this period occurred at the state level. By 1815, various state governments had issued approximately 1,400 official prayer proclamations – roughly half for thanksgiving and half for fasting and prayer.

State governors including Thomas Jefferson, John Hancock, and Samuel Adams all issued Thanksgiving proclamations. Jefferson’s 1779 Virginia proclamation asked citizens to thank God for “the Holy Scriptures which are able to enlighten and make us wise to eternal salvation.”

These proclamations were consistently religious in content and purpose. Thanksgiving was understood as a religious observance with civic dimensions, not a secular harvest celebration.

The tradition remained inconsistent and mostly regional until Abraham Lincoln nationalized it during the Civil War. Lincoln established Thanksgiving as an annual federal holiday in 1863, hoping to unite a divided nation through shared gratitude and religious observance.

How The Pilgrim Story Took Over

The 1621 feast remained obscure until the 19th century, when Americans began searching for founding mythology that wasn’t British. The Revolutionary generation celebrated independence from Britain – they needed different origin stories.

The pilgrim narrative served that need perfectly. It pushed American origins back to 1620 instead of 1776, before British control. It featured religious freedom and self-governance themes that resonated with 19th-century Americans. And it included Indigenous people, allowing the narrative to claim cross-cultural harmony (while conveniently ignoring what came after that 50-year peace treaty ended).

By the late 1800s, the pilgrim story had largely replaced the Constitutional story as Thanksgiving’s popular origin. Elementary schools taught the 1621 feast as “the first Thanksgiving.” The holiday became about pilgrims, not presidents.

This mythology persists because it’s more appealing than the actual history. A heartwarming story of people from different cultures sharing a meal is more comforting than a story about political alliances born of desperation, disease, and mutual strategic interest.

And a story about grateful colonists is more elementary-school-appropriate than a story about grave-robbing Europeans settling on land recently emptied by epidemic disease.

What Gets Lost When We Forget The Real Origin

Thanksgiving’s actual origin – Washington declaring national gratitude for constitutional government and surviving revolution – carries different lessons than the pilgrim mythology.

The Constitutional Thanksgiving teaches that Americans should be grateful for a functioning republic, for civil and religious liberty, for the peaceful resolution of political disputes through law rather than violence. These were radical achievements in 1789.

The pilgrim mythology teaches a simpler lesson about sharing and cross-cultural friendship that bears little resemblance to the actual complexity of colonial-Indigenous relations.

Washington’s proclamation also acknowledges national failings – he asked Americans to pray for pardon of “national and other transgressions.” The founding generation recognized their republic was imperfect and required divine assistance and human improvement.

The sanitized pilgrim story implies everything worked out fine from the beginning, erasing the conflict, disease, and eventual violence that characterized actual colonial history.

The Thanksgiving That Celebrates What, Exactly?

Modern Thanksgiving lacks clear meaning precisely because its origin story is mythological rather than historical. Are we celebrating:

- A harvest meal that happened once in 1621 and was never repeated?

- Generic gratitude without specific object?

- Family togetherness and abundant food?

- Constitutional government and republican survival (the actual origin)?

- Indigenous-colonial cooperation (which lasted 50 years then ended in violence)?

The holiday can be any of these because we’ve forgotten it was created specifically to celebrate the Constitution and the end of the Revolutionary War. Washington didn’t declare Thanksgiving for a harvest or a meal – he declared it for a republic.

Whether Americans should return to that original meaning, or whether the holiday has properly evolved into something more secular and personal, is a question worth debating. But the debate requires knowing what Thanksgiving actually commemorated originally.

The First Congress, the Bill of Rights, and a presidential proclamation thanking God for constitutional liberty – that’s the real origin. Pilgrims came into the story 220 years later when Americans needed mythology more appealing than constitutional history.

George Washington created Thanksgiving as we know it. Not in 1621, but in 1789. Not for a harvest feast, but for a Constitution. Not about pilgrims and Indians, but about surviving revolution and establishing a republic.

The mythology is more comfortable than the history. But the history is more relevant to understanding what Americans were actually grateful for when this holiday began – and what we might consider being grateful for now.