President Trump fired Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook on January 21, his first full day back in office. The termination letter cited “poor performance” and “low intelligence.” Cook sued within hours, arguing the president has no constitutional authority to fire Fed governors.

Now the Supreme Court must answer a question that cuts to the core of presidential power: Can a president fire independent agency officials at will, or do congressional protections limiting removal survive constitutional scrutiny?

The answer determines whether the Federal Reserve, SEC, FTC, NLRB, and dozens of other independent agencies remain truly independent – or whether they become extensions of presidential control, fireable the moment they displease the White House.

Who Lisa Cook Is

Lisa Cook became the first Black woman to serve on the Federal Reserve Board of Governors when she was confirmed by the Senate in May 2022. She was nominated by President Biden and confirmed 51-50 with Vice President Kamala Harris breaking the tie.

Cook is an economist who taught at Michigan State University for over two decades. Her academic work focused on economic growth, innovation, and the relationship between violence and economic opportunity for African Americans in the early 20th century.

Her research documented how lynchings and racial violence destroyed Black wealth and innovation. One influential paper showed that patents by African American inventors declined sharply in regions with higher rates of racial violence.

She holds a PhD in economics from the University of California, Berkeley, bachelor’s degrees from Spelman College, and studied at Oxford University as a Marshall Scholar. Before joining the Fed, she served on the White House Council of Economic Advisers during the Obama administration.

Cook’s 14-year term as Fed governor was set to expire in 2036. Trump terminated her 13 years early.

The Termination Letter

Trump’s termination letter was brief and personal. It stated Cook was being removed for “poor performance” and “low intelligence” – language rarely seen in official presidential actions removing Senate-confirmed officials.

The letter provided no specific performance failures, no documentation of incompetence, no examples of decisions or analysis demonstrating the alleged low intelligence. Just the assertion that she performed poorly and lacked adequate intelligence for the position.

Cook’s lawsuit argues the language itself demonstrates the firing was pretextual – political disagreement disguised as performance-based removal. Fed governors serve staggered 14-year terms specifically to insulate them from political pressure and ensure monetary policy independence.

Trump has long criticized the Federal Reserve when it makes decisions he opposes. He attacked Chair Jerome Powell – whom Trump himself appointed – multiple times during his first term for not lowering interest rates fast enough. He called Powell an “enemy” at one point.

Cook has been more willing than some Fed governors to maintain higher interest rates to combat inflation. Whether that policy disagreement constitutes “poor performance” is now a constitutional question.

The Federal Reserve Act’s Removal Provision

The Federal Reserve Act, passed in 1913, allows the president to remove Fed governors only “for cause.”

The statute doesn’t define “cause,” but courts have generally interpreted it to mean misconduct, neglect of duty, or incapacity – not policy disagreement or presidential displeasure.

The “for cause” removal protection is central to Fed independence. Presidents appoint governors and the Senate confirms them, but once confirmed, governors serve 14-year terms protected from political removal.

This structure is supposed to prevent presidents from firing Fed governors who make monetary policy decisions the president opposes.

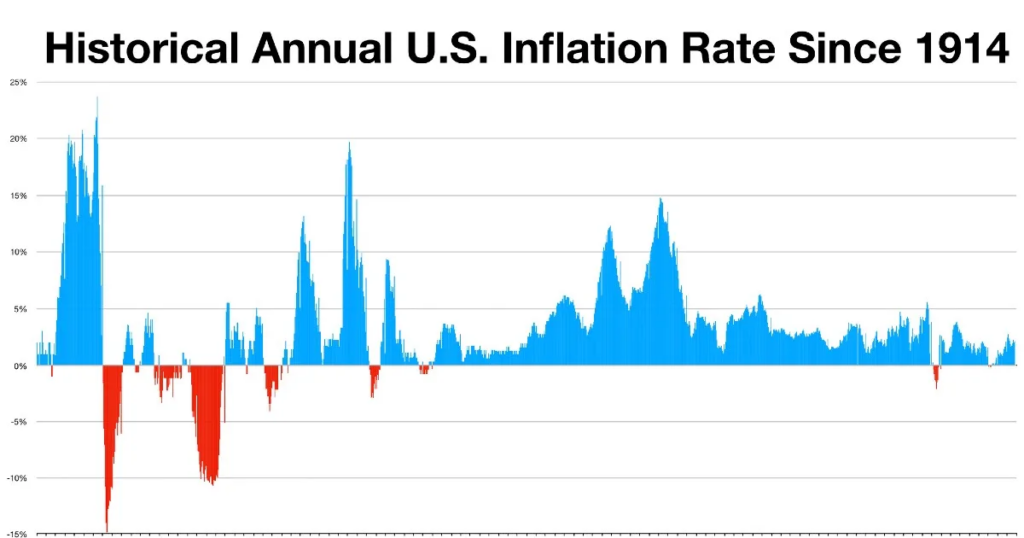

Controlling inflation sometimes requires raising interest rates, which slows economic growth and can hurt a president politically. The “for cause” protection allows governors to make economically necessary but politically unpopular decisions.

Trump’s position is that “for cause” removal restrictions are unconstitutional. He argues Article II vests all executive power in the president, which includes the power to remove executive branch officials. Congress cannot limit that removal power through statutes like the Federal Reserve Act.

Cook’s position is that the Fed is not a typical executive agency. It’s an independent agency Congress created with specific removal protections to ensure monetary policy independence from political pressure.

Those protections are constitutional exercises of Congress’s power to structure government.

The Supreme Court Precedent That Complicates Everything

The Supreme Court addressed presidential removal power in Humphrey’s Executor v. United States in 1935. The case involved President Franklin Roosevelt firing a Federal Trade Commissioner before his term expired. The FTC statute allowed removal only “for cause.”

The Court ruled that Congress can limit presidential removal power for officials in independent agencies performing quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial functions. The president can’t fire them at will – only for cause as defined by statute.

But the Court also decided Myers v. United States in 1926, holding that the president has unlimited power to remove purely executive officers. Congress can’t restrict removal of officials exercising core executive functions.

The tension between these cases has never been fully resolved. Which agencies are “independent” enough that Congress can protect their officials from at-will removal? Which officials are “executive” enough that presidential removal power cannot be restricted?

The Cook case forces the Supreme Court to clarify or potentially overturn this framework.

The Unitary Executive Theory

Trump’s legal argument relies on “unitary executive theory” – the view that Article II vests all executive power in the president, making him the sole head of the executive branch with complete control over everyone exercising executive power.

Under this theory, Congress cannot create independent agencies whose officials the president cannot fire at will. Any exercise of executive power must be subject to presidential control, including removal.

Unitary executive proponents argue this is what the Framers intended. Article II says “the executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America” – not in independent agencies, not in officials with job protection, but in the president personally.

If executive power is truly vested in one person, that person must have power to remove subordinates exercising that power. Otherwise, executive power is divided rather than unitary, violating the constitutional structure.

Conservative legal scholars and judges have embraced unitary executive theory for decades. The current Supreme Court’s conservative majority includes justices sympathetic to this view.

Why Fed Independence Exists

The Federal Reserve was deliberately structured as independent from presidential control because history showed central banks controlled by politicians make disastrous monetary policy decisions.

Politicians want low interest rates and easy money – it stimulates growth and helps them win elections. But keeping rates too low causes inflation. Controlling inflation requires raising rates, which slows growth and hurts politicians electorally.

If presidents could fire Fed governors for raising rates, monetary policy would become political.

Governors would keep rates low to avoid getting fired. Inflation would accelerate. Long-term economic stability would be sacrificed for short-term political gain.

The 14-year terms and “for cause” removal protection exist precisely to prevent this dynamic. Governors can make economically necessary but politically unpopular decisions without fear of being fired for disagreeing with the president.

That independence is why the Fed has credibility with markets. Investors and foreign governments trust that Fed decisions are based on economic analysis rather than political pressure. That trust is valuable – it keeps borrowing costs lower and financial markets more stable.

Trump’s firing of Cook tests whether that independence survives constitutional scrutiny.

The “Poor Performance” and “Low Intelligence” Language

Trump’s termination letter language is constitutionally significant. “Poor performance” and “low intelligence” could theoretically constitute “for cause”—if proven with documentation and evidence.

But Trump provided no evidence. No performance reviews showing failures. No examples of analytical errors demonstrating low intelligence. Just assertions.

Cook’s lawsuit argues this proves the firing was pretextual— – rump fired her for policy disagreement but dressed it as performance-based removal to claim compliance with “for cause” requirements.

If courts defer to presidential assertions of “poor performance” without requiring proof, the “for cause” protection becomes meaningless. Presidents could fire anyone by claiming poor performance, even when the real reason is policy disagreement.

If courts require presidents to document performance failures, the protection has teeth. Presidents must build cases for removal rather than firing officials at will.

The Supreme Court must decide how much deference presidents get when they claim “for cause” exists.

The Broader Implications Beyond the Fed

The Supreme Court’s ruling will affect dozens of independent agencies – not just the Federal Reserve.

The Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Trade Commission, National Labor Relations Board, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and many others have similar “for cause” removal protections.

If the Court rules those protections are unconstitutional, presidents gain power to fire commissioners and board members at will. Every independent agency becomes subject to direct presidential control.

The regulatory state transforms overnight. Agencies designed to be independent from political pressure become extensions of presidential power. Every agency head serves at presidential pleasure.

If the Court upholds removal protections, the current structure survives. Presidents must live with officials they cannot fire, even when those officials make decisions the president opposes.

The Conservative Legal Movement’s Goal

Conservative legal scholars have sought to dismantle independent agencies for decades.

They argue the administrative state has grown unconstitutionally, creating a “fourth branch” of government the Framers never intended.

The unitary executive theory provides the constitutional argument for presidential control over this administrative apparatus. If all executive power must be subject to presidential removal authority, independent agencies cannot exist in current form.

The Cook case gives the Supreme Court’s conservative majority an opportunity to implement this theory. Overruling Humphrey’s Executor and requiring at-will presidential removal for all agency officials would be the biggest structural change to the administrative state in nearly a century.

Oral arguments revealed the conservative justices are seriously considering exactly that outcome.

What Happened at Oral Arguments

The January 14 oral arguments showed a Court deeply divided along ideological lines, with conservative justices skeptical of removal protections and liberal justices warning of consequences.

Chief Justice Roberts questioned whether Humphrey’s Executor remains good law. He suggested the distinction between executive agencies and independent agencies is unworkable.

Justice Alito pressed Cook’s attorney on how much executive power can be placed beyond presidential control before the president becomes unable to execute the laws faithfully.

Justice Gorsuch explored whether any removal restrictions survive if executive power truly vests in the president alone.

Justice Kavanaugh asked whether the unitary executive theory is too absolute or whether some limited removal protections might be constitutional.

Justice Barrett questioned what happens to agency independence and expertise if all officials become politically vulnerable to firing.

The liberal justices – Sotomayor, Kagan, and Jackson – warned that eliminating removal protections would politicize technical agencies and destroy institutional expertise.

Justice Kagan noted the Fed was created precisely because monetary policy needed independence from political pressure. Removing that independence threatens economic stability.

Justice Sotomayor asked whether Trump’s vague “poor performance” claim demonstrates why protections matter – preventing pretextual firings disguising political disagreement.

The Financial Markets Are Watching

Markets reacted negatively when Trump fired Cook. The uncertainty about Fed independence and monetary policy created volatility.

If the Supreme Court upholds Trump’s removal power, markets will price in increased political control over Fed decisions. Interest rate expectations will factor in presidential preferences rather than just economic conditions.

That uncertainty increases borrowing costs for everyone—government, businesses, individuals. When markets doubt Fed independence, they demand higher interest rates to compensate for political risk.

The economic cost of destroying Fed independence could be enormous—trillions in higher borrowing costs over time.