Senator John Kennedy has a message for his own party: You’re wasting the majority you fought for.

The Louisiana Republican wants Congress to use budget reconciliation again – the brutal legislative process that consumed months of 2025 and nearly fractured the GOP coalition. Republicans used it once to pass Trump’s tax package. Kennedy says they should use it again to tackle the cost of living crisis that voters elected them to solve.

His own leadership won’t do it.

“I am at a loss to understand why our leadership will not agree to another reconciliation,” Kennedy told Fox News. He pointed out that Democrats would jump at the chance to pass their priorities without needing a single Republican vote. “If you went to Senator Schumer right now and said, ‘you have the chance to pass anything you want,’ what do you think Chuck would do? He’d take a dozen.”

The answer to Kennedy’s question reveals something uncomfortable about constitutional governance: having the power to act and choosing to use it are two different things. Republicans control both chambers of Congress and the White House. They have the procedural tools to advance their agenda without Democratic cooperation. And they’re choosing not to use them.

What Budget Reconciliation Actually Allows

Budget reconciliation is a special legislative process that bypasses the Senate’s 60-vote filibuster requirement. It only requires a simple majority – 51 votes in the Senate, 218 in the House. That means the party in power can pass major legislation without needing any support from the minority.

The Constitution doesn’t mention reconciliation. It’s a creature of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, which created expedited procedures for legislation affecting federal spending, revenue, and the debt limit. The theory is that budget matters are urgent enough to justify limiting debate and amendments.

But there’s a catch called the Byrd Rule, named after the late Senator Robert Byrd. It prohibits including provisions in reconciliation bills that don’t have a direct budgetary impact. You can’t just shove any policy you want into a reconciliation bill and call it budget-related. The Senate parliamentarian enforces the rule by determining what qualifies.

Kennedy acknowledges this constraint but argues it shouldn’t stop Republicans from trying. There are plenty of regulatory reforms, spending cuts, and tax changes that would survive Byrd Rule scrutiny while addressing affordability. The question isn’t whether reconciliation could work – it’s whether leadership wants to attempt it.

Why Trump’s First Reconciliation Nearly Broke the GOP

Republicans already used reconciliation once in 2025 to pass what Trump called his “one big, beautiful bill” – a massive tax package that tested party unity to its breaking point.

The process took months. Every faction demanded concessions. Moderates wanted spending offsets. Conservatives wanted deeper cuts. Members from high-tax states wanted SALT deduction relief. Rural members needed agriculture provisions. The bill survived by a handful of votes after leadership made deals that barely held the coalition together.

That experience left scars. Getting 218 House Republicans and 51 Senate Republicans to agree on anything requires extraordinary political capital. Leadership spent months negotiating, horse-trading, and pleading to pass one bill. The idea of immediately reopening that process makes most lawmakers queasy.

Kennedy’s response is essentially: so what? You have the majority. Use it or lose it.

“Yes, we passed the ‘one big, beautiful bill,’ that was July 1, five months ago, now, almost six months ago,” Kennedy said. “We need to act.”

The constitutional question isn’t whether Congress can use reconciliation multiple times – the Budget Act allows it. The question is whether the political will exists to endure another brutal negotiation that could fracture the coalition and produce little to show for the effort.

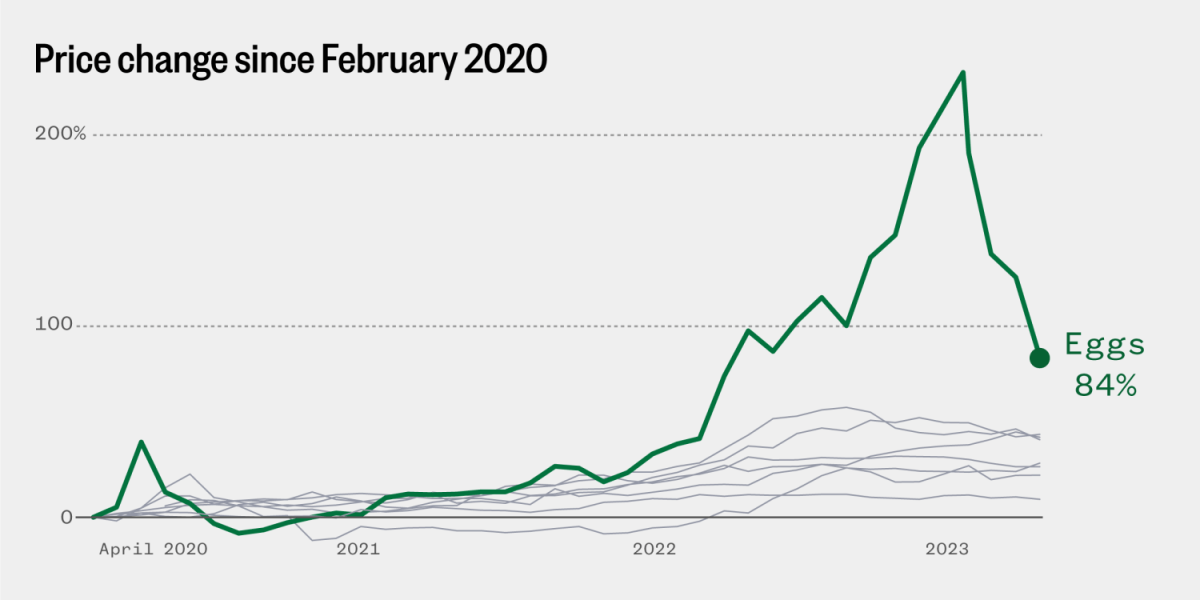

The Cost of Living Problem Republicans Promised to Solve

Trump campaigned on bringing down inflation and making life affordable again. Voters gave Republicans unified control specifically to deliver on that promise. Five months after passing the tax bill, prices are still high, and voters are still getting squeezed.

Kennedy wants to use reconciliation to address regulations that add roughly $2 trillion to the cost of goods and services. Federal rules governing everything from energy production to labor standards to environmental compliance increase costs that get passed to consumers. Rolling back those regulations would theoretically reduce prices.

The problem is that regulatory reform walks a constitutional tightrope. Congress can pass laws eliminating specific regulations. But many regulations come from executive agencies implementing statutes Congress already passed. Changing those requires either new legislation directing agencies differently or executive action under existing law.

Reconciliation could include provisions directing agencies to repeal costly rules, defunding enforcement mechanisms, or blocking specific regulations from taking effect. Whether those provisions survive the Byrd Rule depends on whether they have sufficient budgetary impact – which the parliamentarian would decide case-by-case.

Kennedy’s argument is that Republicans should at least try. Leadership’s calculus appears to be that the political cost of failure outweighs the benefit of attempting something that might not work.

The Obamacare Subsidy Fight That Just Collapsed

Kennedy’s push comes as Congress failed to address expiring Obamacare subsidies that will cause healthcare premiums to spike for millions of Americans. Both parties introduced proposals last week. Both failed. Now a bipartisan group led by Senators Susan Collins and Bernie Moreno is trying to find middle ground.

Senator Bill Cassidy, who helped craft the Republican healthcare proposal, admitted “the calendar precludes getting something done this week.” Translation: Congress is running out of time before subsidies expire, and there’s no agreement on how to prevent the premium increases voters will blame Republicans for.

This is exactly the kind of affordability crisis Kennedy wants reconciliation to address. Healthcare costs are rising. Republicans control Congress. And instead of using their procedural advantage to pass a fix without Democratic votes, they’re negotiating with Democrats and running out of time.

The constitutional framework gives the majority party tools to act unilaterally. The political reality is that using those tools requires unity the party doesn’t have and risks backlash if the effort fails.

What “Wasting the Majority” Actually Means

Kennedy’s criticism cuts to a fundamental tension in constitutional governance: voters elect majorities to accomplish things, but the Constitution makes accomplishing things extraordinarily difficult even when one party controls everything.

The House and Senate operate under different rules. Narrow majorities in both chambers mean every member has veto power. The Byrd Rule limits what reconciliation can include. And even when you have the votes, getting agreement on what to pass requires satisfying competing factions with incompatible demands.

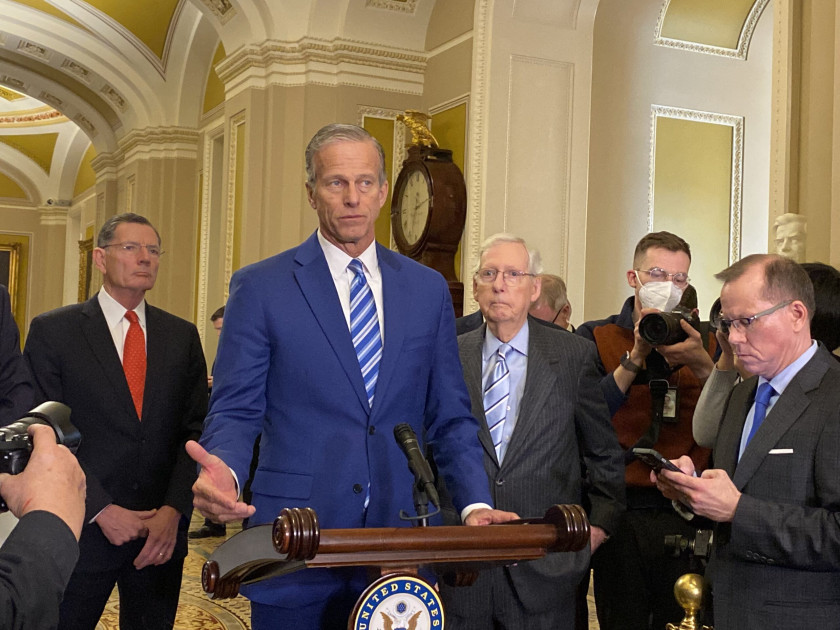

Senate Majority Leader John Thune, whom Kennedy pointedly called “a friend” while criticizing his reluctance to pursue another reconciliation bill, faces these constraints every day. He knows attempting reconciliation again could fail spectacularly, fracture the party, and consume months that could be spent on other priorities.

Kennedy’s counter-argument is that having a majority means nothing if you don’t use it. Voters didn’t elect Republicans to be cautious. They elected them to bring down costs. If leadership won’t use the tools available to deliver, what’s the point of having the majority?

This isn’t a constitutional question with a right answer. It’s a strategic judgment about risk tolerance and political capital. The Constitution gives Congress the power to legislate. It doesn’t tell leadership when to spend that power or whether preserving unity matters more than attempting ambitious policy.

The Byrd Rule as Constitutional Constraint

The Byrd Rule deserves special attention because it’s a self-imposed congressional constraint that functions almost like a constitutional provision in practice.

Congress could change or eliminate the Byrd Rule at any time – it’s just a Senate rule, not a statute or constitutional requirement. But doing so would fundamentally alter how reconciliation works and invite future majorities to cram non-budgetary policies into reconciliation bills without limit.

The rule exists to prevent exactly what Kennedy wants: using reconciliation as a general-purpose tool to pass any legislation the majority favors. Reconciliation was designed for budget matters. The Byrd Rule keeps it that way by excluding provisions without direct fiscal impact.

Kennedy argues that regulatory reform does have fiscal impact – reducing compliance costs, lowering prices, affecting federal revenue. But the parliamentarian decides what counts as “direct” impact, and many regulatory changes get ruled out because the budgetary effects are too indirect or speculative.

This creates a perverse outcome: the majority party has a procedural tool to bypass filibusters, but can only use it for a narrow category of legislation. Meanwhile, the broader policy agenda that voters elected them to enact remains subject to the 60-vote threshold they can’t reach.

Congress designed this system deliberately. The question is whether maintaining that design serves the constitutional function of checks and balances, or whether it just gives majorities an excuse not to deliver on campaign promises.

What Happens If Leadership Doesn’t Relent

Kennedy said he hopes Senator Thune “will relent and agree to another reconciliation bill that addresses the cost-of-living issue” after the holidays.

If Thune doesn’t relent, Republicans will spend 2026 facing voters who are still struggling with high prices while Democrats argue the GOP majority accomplished nothing beyond one tax bill that primarily benefited corporations and wealthy individuals.

That’s terrible politics for a party that won specifically on economic issues. But it might be better politics than attempting reconciliation, failing to pass anything because of internal divisions, and giving Democrats evidence that Republicans can’t govern even when they control everything.

Leadership is betting that inaction is less damaging than failed action. Kennedy is betting that voters will punish Republicans for having power and refusing to use it.

Both could be right. Voters might blame Republicans for not delivering on affordability. They might also blame Republicans if reconciliation produces a messy legislative fight that goes nowhere while healthcare premiums spike and other urgent issues go unaddressed.

The Constitutional Design That Makes Governing Hard

The Framers didn’t want government to act quickly or easily. They built a system where legislation requires cooperation across multiple institutions with different constituencies and election cycles. Bicameralism, presentment, and the executive veto all create friction that slows down lawmaking.

Modern procedural rules like the filibuster and the Byrd Rule add more friction. Whether those rules serve the Framers’ intent or subvert it is debatable. But the result is clear: having a majority doesn’t guarantee the ability to legislate even on your core priorities.

Kennedy’s frustration represents one view of how majorities should behave: use every procedural tool available, push the boundaries of what’s permitted, deliver for voters who gave you power. It’s an aggressive approach that treats narrow majorities as mandates to act.

Thune’s apparent caution represents another view: preserve party unity, avoid high-risk legislative gambits that could fail, focus on achievable wins rather than ambitious attempts that might fracture the coalition. It’s a conservative approach that treats narrow majorities as requiring consensus rather than enabling unilateral action.

Neither approach is constitutionally required. The Constitution gives Congress broad authority to make its own rules and determine its own priorities. How majorities exercise that authority is a political choice, not a legal mandate.