Republican leaders are pre-emptively attacking Saturday’s “No Kings” national protests before they happen. Speaker Mike Johnson called them “hate-America rallies” that will draw “pro-Hamas” Democrats and “antifa people.” House Republican Whip Tom Emmer warned of widespread “hate for America.” Senator Roger Marshall suggested the National Guard might be necessary and claimed protesters were being paid.

Michael Steele, the former Republican National Committee chairman, responded by calling the coordinated talking points “ridiculous” and urging Republicans to recognize protest as fundamentally American. His commentary raises uncomfortable questions about what protest means in contemporary America – and who gets to decide whether dissent qualifies as patriotism or betrayal.

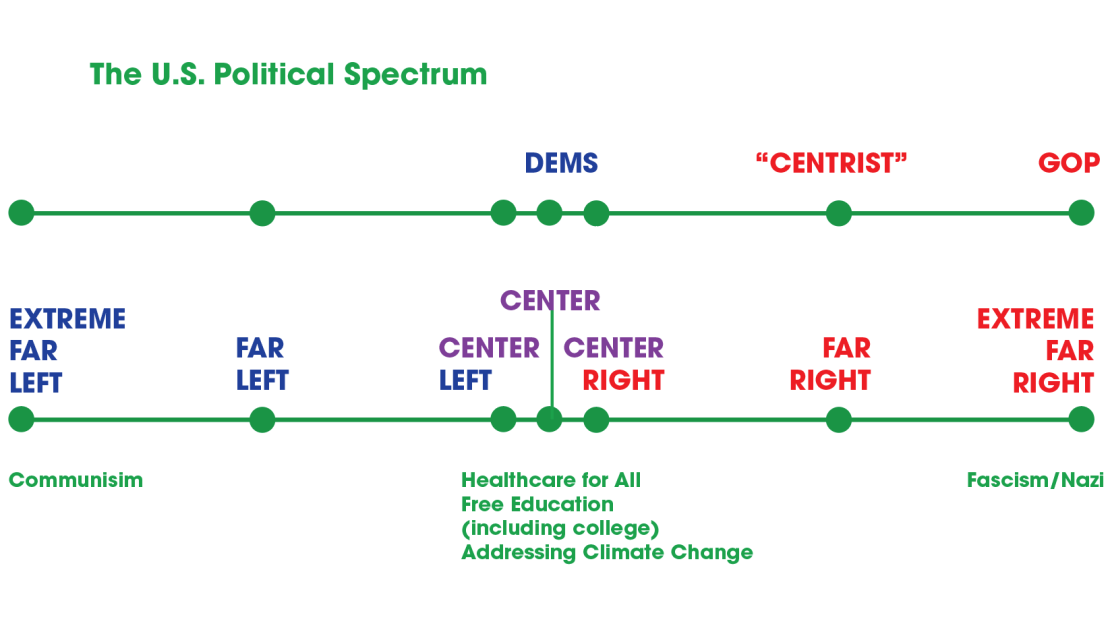

The tension reveals something deeper than disagreement about Trump administration policies. It exposes competing definitions of what it means to be patriotic, what constitutes legitimate dissent, and whether opposing government can be fundamentally American or inherently anti-American.

The Coordinated Message Strategy

Steele’s confession about Republican messaging discipline is revealing. He describes how RNC leadership carefully crafted talking points to keep party members “on message” and prevent anyone from “upending the party message by saying something unhinged.”

He notes that this time, “the unhinged comments are the message.” Republican leaders aren’t accidentally using inflammatory rhetoric – they’re deliberately coordinating it. The language was planned, distributed, and intentionally deployed to frame protests as dangerous, unpatriotic, and potentially treasonous before they occur.

This raises a question about political communication that transcends partisan dispute: When leaders deliberately coordinate inflammatory rhetoric about citizens exercising First Amendment rights, what are they actually accomplishing? Are they engaging in legitimate political opposition, or are they attempting to delegitimize dissent itself?

The pre-emptive attack on protests hasn’t occurred yet represents an attempt to shape how Americans interpret the demonstrations before they happen. By labeling them “hate-America” and associating them with “pro-Hamas” movements and “antifa,” Republican leaders try to poison perception before citizens can observe protests and draw independent conclusions.

What the “No Kings” Message Actually Says

The protest organizers’ message is straightforward: America is a democracy, not a dictatorship. The name itself references the Founders’ rejection of monarchy and establishment of democratic governance. It’s a direct assertion that democratic principles require limits on executive power and that concentrated authority in a single leader constitutes betrayal of constitutional design.

That message doesn’t require agreement with all Trump administration policies to understand. One can support Trump’s immigration enforcement, tax cuts, or judicial appointments while still believing democratic accountability and constitutional limits on executive power matter fundamentally.

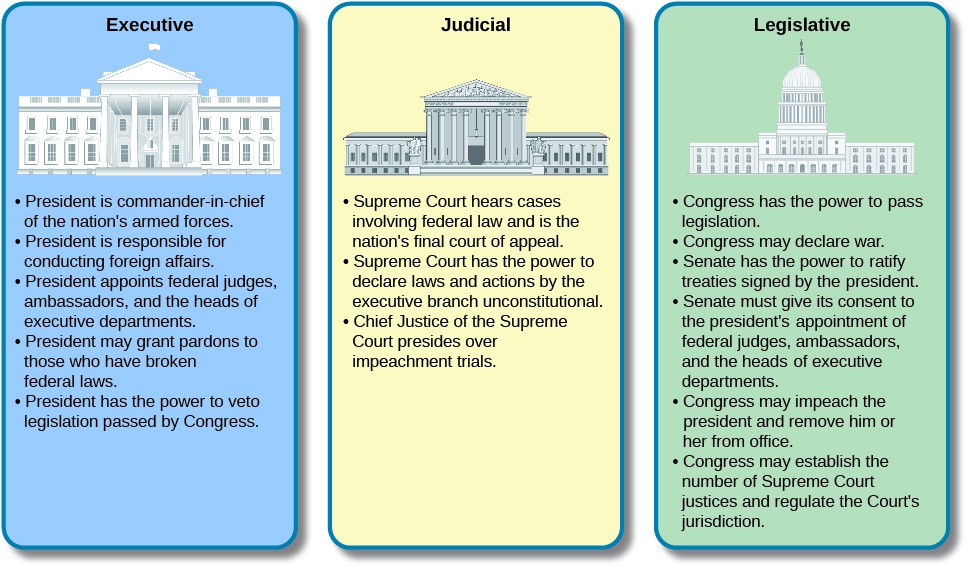

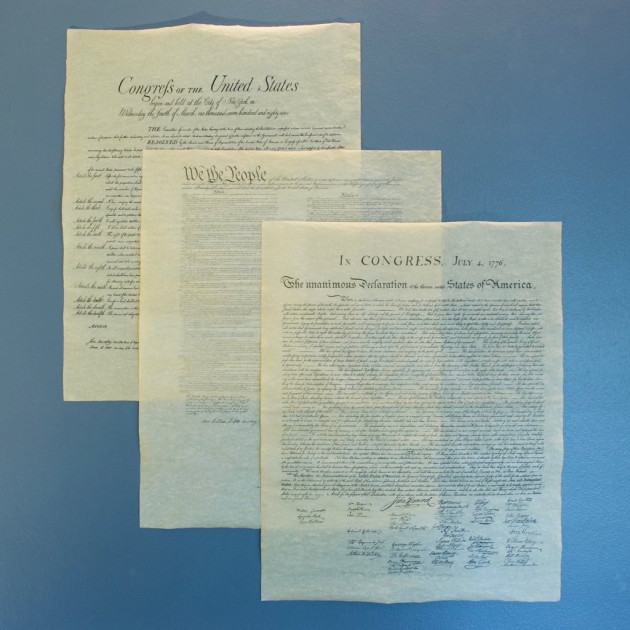

The “No Kings” framing invokes founding principles explicitly. The Declaration of Independence focused on grievances against King George III’s arbitrary authority. The Constitution distributed power across branches specifically to prevent concentration in one person or office. The Tenth Amendment reserved powers to states and people.

Whether contemporary executive power actually resembles “kings” depends on one’s constitutional interpretation. But the protest organizers are asserting an explicitly constitutional argument – not that Trump should be removed from office or that his policies are unjust, but that democracy requires institutional limits on executive power regardless of which party controls it.

Steele’s Uncomfortable Truth About Republican Messaging

Steele’s deeper criticism isn’t just about rhetoric – it’s about what coordinated talking points reveal about Republican strategy. He writes: “Trump-era Republicans do not want to govern for the American people anymore. They want a king.”

That’s a serious charge from a former party leader. He’s not claiming Republicans want a king in literal sense – he’s arguing the party has abandoned its historical commitment to limited government, individual liberty, and institutional checks on executive power in favor of loyalty to Trump personally.

Steele emphasizes the contradiction: “The same party that once celebrated individual liberty and limited government now demands loyalty to a single leader, punishes dissent and attacks the free press.”

This observation troubles the foundational question of American governance. If true, Steele identifies a fundamental shift in Republican ideology away from constitutional principles toward personality-based authoritarian loyalty. That’s distinct from normal political opposition – it suggests institutional transformation rather than policy disagreement.

But Steele’s analysis itself warrants scrutiny. Is he accurately describing Republican priorities, or is he projecting his own political opposition onto the party? Do coordinated talking points actually indicate desire for authoritarian leadership, or do they reflect normal political communication strategy that both parties employ?

The Protest as Patriotism Versus Betrayal Framing

Steele frames protest as quintessentially patriotic – “the most American way possible” to defend constitutional rights. Protesters “refuse to accept authoritarianism as the new normal” and “are choosing to push back” through “peaceful assembly.”

Republican leaders frame the same protests as “hate-America,” potentially dangerous, and associated with anti-patriotic movements. The same activity – protest – receives diametrically opposite characterizations depending on partisan perspective.

This raises the central interpretive question: Can both framings be partially true? Or does one side necessarily mischaracterize what’s happening?

Historically, dissent has served patriotic functions – abolitionists opposed slavery, civil rights activists challenged segregation, Vietnam War protesters questioned government authority. But dissent can also reflect legitimate disagreement about policy without suggesting the government itself is anti-democratic.

The “No Kings” protesters appear to assert the latter – not that all Trump administration policies are unjust, but that democracy requires institutional limits on executive power. That’s a constitutional argument about structure rather than policy critique.

Republican leaders’ response frames such structural argument as fundamentally un-American. That framing assumes that supporting current government leadership constitutes patriotism and that opposing executive power constitutes betrayal.

The Institutional Silence Question

Steele raises a provocative observation: Only Barack Obama has “spoken with clarity and courage about the danger of authoritarianism” among former presidents. Where, he asks, is George W. Bush? Where are Republican elder statesmen willing to defend constitutional principles against their own party?

The silence itself communicates something. If former conservative leaders believed Trump administration actually threatened constitutional democracy, wouldn’t they say so? Their failure to speak suggests either:

- They don’t believe the threat is as severe as “No Kings” protesters claim

- They do believe it but fear party repercussions more than constitutional concerns

- They disagree with how the threat is being characterized

Each possibility raises uncomfortable questions about institutional commitment to constitutional principles versus partisan loyalty.

Steele’s implicit argument is that Bush and others have moral obligation to speak out. But that argument assumes facts not necessarily established – that constitutional democracy actually faces existential threat requiring elder statesmen intervention. If Bush believes the Trump administration, while imperfect, operates within constitutional bounds, silence might reflect disagreement rather than cowardice.

The Dangerous Assumption in Steele’s Framing

Steele characterizes Trump as a “wannabe tyrant king” and “Mad King.” Those are serious characterizations implying that democracy itself faces threat and that normal political opposition is insufficient response.

But such language requires proof. What specific executive actions constitute attempted authoritarianism? What distinguishes Trump’s exercise of executive power from previous presidents’ assertions of executive authority? Where are the institutions actually breaking down?

Trump’s policies – immigration enforcement, personnel decisions, press restrictions – reflect different approach to executive power than Biden’s or Obama’s administrations. But different approach doesn’t automatically constitute authoritarianism.

Steele’s argument conflates policy disagreement with constitutional threat. That conflation risks normalizing serious charges of authoritarianism when applied to routine presidential decisions. Simultaneously, it may cause citizens to dismiss genuine constitutional concerns if they become routine partisan accusations.

The “Antifa” and “Pro-Hamas” Framing Question

Republican leaders assert that “No Kings” protests will include “antifa people” and “pro-Hamas” elements. These claims appear designed to associate protests with violence and anti-American causes regardless of the protests’ actual composition or message.

But such framing assumes facts not established. Do historical protest associations actually predict Saturday’s protests? Will “antifa” actually show up, or are Republicans pre-emptively delegitimizing by invoking threatening imagery?

This represents a different kind of dangerous assumption – that associating a movement with radical elements suffices to discredit it regardless of whether those elements actually participate or what the stated message actually is.

Both Steele and Republican leaders engage in interpretive framing that assumes their characterization rather than proving it. Steele assumes Trump represents authoritarian threat requiring constitutional defense. Republicans assume protests represent dangerous anti-American activity requiring preemptive delegitimization.

What Actually Constitutes Legitimate Dissent?

The underlying question both sides grapple with is: What distinguishes legitimate protest from dangerous radicalism? When can opposing government constitute patriotism versus betrayal?

Democratic theory assumes dissent operates within framework of accepting democratic legitimacy. Protest can oppose policies or even officials while still accepting democratic institutions and processes. Once dissent moves to questioning the government’s fundamental legitimacy or threatening democratic processes themselves, it potentially crosses into dangerous territory.

“No Kings” framing invokes constitutional principles but potentially questions the legitimacy of current leadership. That’s different from opposing specific policies while accepting electoral process and constitutional structure.

The question is whether such questioning constitutes legitimate democratic discourse or represents the kind of delegitimation that threatens democratic stability.

The Historical Parallels That Don’t Quite Work

Steele invokes founding era parallels: “We were once colonists, beholden to the whims and cunning of a Mad King. Today we are Americans, emboldened by our faith in ‘We the People.’”

The analogy suggests contemporary situation resembles colonial subjugation. But the parallel strains under scrutiny. Colonists lacked representation entirely. Americans have elections, divided government, free press, and multiple institutions constraining executive power. Those differences matter.

Invoking revolutionary rhetoric to describe contemporary elections and institutional opposition risks normalizing extreme language for normal democratic disagreement. But similarly, dismissing such comparisons entirely assumes the systems actually functioning as designed without examining whether power concentration has actually shifted.

The Coordinated Messaging Problem Both Sides Exhibit

Steele criticizes Republican coordination of inflammatory talking points. But Democratic and progressive organizations have similarly coordinated messaging about Trump’s threat to democracy. Both sides employ strategic framing to interpret events in ways supporting their political goals.

This doesn’t prove both sides are equally right or wrong. But it reveals that both rely on interpretive framing more than objective facts to characterize what’s happening and what it means.

What Actually Matters

The real constitutional question isn’t whether Republicans or Steele correctly characterize Trump’s threat level. It’s whether institutional checks on executive power – Congress, courts, press, elections – continue functioning to restrain executive authority regardless of partisan control.

Those institutions have produced outcomes Democrats oppose: Trump’s judicial appointments, immigration policies, personnel decisions. That opposition doesn’t indicate institutional failure – it indicates democracy functioning through institutions producing outcomes different constituencies dislike.

Constitutional threat would manifest as institutions failing to restrain executive power, not as institutions producing outcomes political opposition dislikes.

The Real Problem Steele Identifies

Beneath the partisan debate, Steele identifies something legitimate: If Republican Party has shifted from defending constitutional limits on power to defending presidential power regardless of limits, that represents institutional problem transcending any single president.

Party commitment to constitutional structure matters more than particular leaders. If commitment erodes based on partisan control, constitutional system degrades.

Similarly, if Democratic opposition to executive power evaporates when their party controls it, that erodes commitment to constitutional principles rather than defending them.

What Saturday’s Protests Might Reveal

The protests themselves will be revealing. Do they focus on constitutional structural concerns or simply policy opposition? Do demonstrators encompass diverse ideological perspectives united by constitutional concerns, or do they represent primarily partisan opposition?

Do Republican fears of violence materialize, or do they mischaracterize peaceful assembly? Do protest organizers maintain message discipline around constitutional concerns or allow association with more radical elements?

The actual events will provide evidence for assessing whether Steele and Republicans are accurately characterizing what’s happening or whether they’re interpreting normal democratic activity through partisan lenses.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The real problem neither Steele nor Republican leaders adequately address is this: Contemporary America doesn’t have agreed-upon standards for distinguishing legitimate constitutional concerns from partisan opposition. Both sides invoke constitutional principles. Both coordinate messaging. Both assume their interpretation of events is accurate while opponent’s is distorted.

That lack of shared interpretive framework makes healthy democratic disagreement harder. When citizens can’t agree on basic facts about whether government operates constitutionally, or whether opposition constitutes patriotism versus betrayal, institutional trust erodes regardless of which party’s characterization is more accurate.

Saturday’s protests won’t resolve that disagreement. They’ll illustrate it. And the question of whether peaceful assembly constituting dissent against government qualifies as patriotic exercise of constitutional rights or dangerous anti-American activity will remain contested.