Can a president ignore a court order and still claim to uphold the rule of law? That question continues to intensify following new statements from the Trump White House, which forcefully rejected recent criticism over the deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia to El Salvador.

Responding to concerns raised by Senator Chris Van Hollen and public commentary on the case, the administration declared that Abrego Garcia—deported in violation of a federal court order—would “not be coming back” to the United States. The White House also attacked the framing of the case in national reporting, calling it misleading and politically motivated.

But beyond the headlines lies a growing constitutional crisis: how far can executive power go in rejecting judicial oversight, and what happens when two branches of government fundamentally disagree about the law?

The Executive Response

The administration’s firm stance followed criticism from lawmakers and legal observers who pointed to a recent court order directing the government to facilitate Abrego Garcia’s return. That order came after the Department of Homeland Security admitted he was removed despite a legal stay that should have protected him from deportation.

In private assurances, the White House reportedly told Senator Van Hollen that the individual in question—Abrego Garcia—would not be returned under any circumstances. In public statements, the administration argued that the deportation was both legally sound and justified on national security grounds.

The case has since become a lightning rod in the larger debate over immigration, executive discretion, and compliance with federal court rulings.

What the Courts Have Ordered

Federal judges have made clear that the deportation violated existing legal orders. Multiple court decisions have instructed the executive branch to act affirmatively to bring Abrego Garcia back to the United States, or at minimum demonstrate good-faith efforts to do so.

When those orders were met with resistance or silence, courts began to explore the possibility of contempt proceedings—potentially holding executive officials accountable for failing to follow binding judicial mandates.

In response, administration attorneys have argued that the courts lack authority to compel the president to conduct foreign policy, including negotiating with El Salvador for the return of a deportee. They also cite national security concerns and confidential investigative materials as justification for resisting compliance.

The Constitutional Clash

At its core, the dispute is about more than one individual—it’s a direct test of constitutional balance. The judiciary has long held the power to issue orders and enforce rights. But that authority relies on the executive branch’s cooperation. When the executive refuses to act, even under court instruction, it raises the specter of constitutional breakdown.

The Founders envisioned a government of checks and balances: the courts to interpret the law, the executive to enforce it. But when the enforcer decides a law—or a ruling—is optional, the entire structure is threatened.

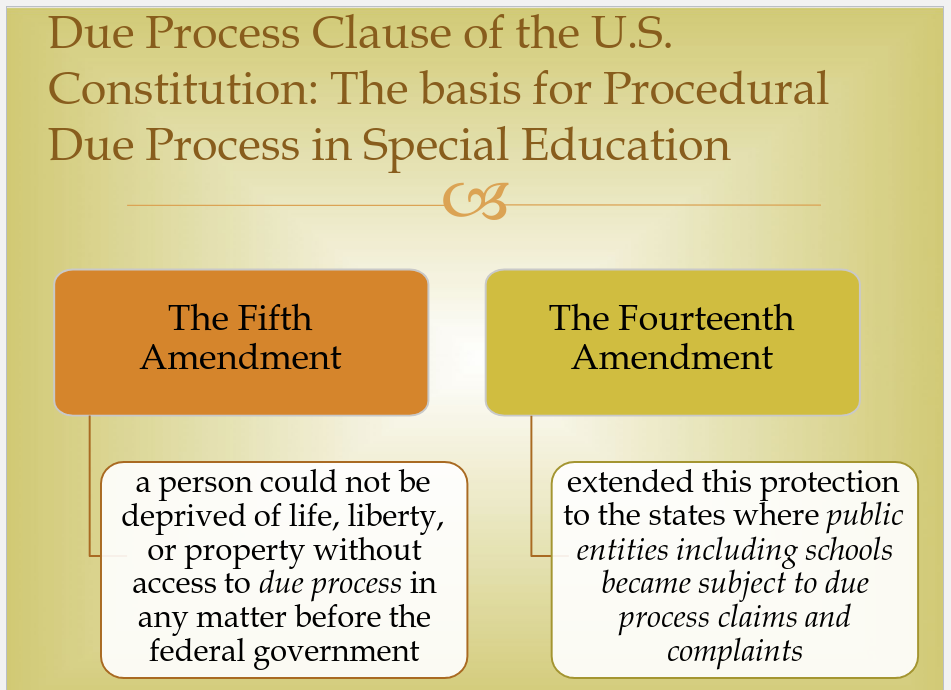

This case also engages the Fifth Amendment’s guarantee of due process. Abrego Garcia had legal protections that were stripped away through his removal. Whether the government can now refuse to remedy that violation—on its own terms—raises questions about whether constitutional rights are contingent on political will.

Diplomatic Complexity or Legal Evasion?

The administration argues that it cannot force a foreign government to release an individual, especially one now held in a high-security facility. That’s true. But courts have not ordered results—they’ve ordered effort: engagement, negotiation, and a demonstration that the executive takes the rule of law seriously.

Presidents have previously repatriated individuals wrongly deported, sometimes with the cooperation of foreign governments, sometimes without. The refusal to even attempt such efforts in this case has led critics to argue that the administration is stonewalling—not because it can’t comply, but because it won’t.

If allowed to stand, such a precedent could empower future administrations to ignore court rulings whenever they conflict with executive priorities, gutting the principle that no one—not even the president—is above the law.

Conclusion

The administration’s categorical rejection of judicial orders in the Abrego Garcia case, and its defiant messaging in response to criticism, has transformed a legal error into a constitutional standoff. The question now is not whether the government made a mistake—it has admitted as much—but whether it will take responsibility.

The courts have spoken. The president has replied. What remains is a fundamental test of the American system: Will one branch of government enforce the rights the other is determined to ignore?