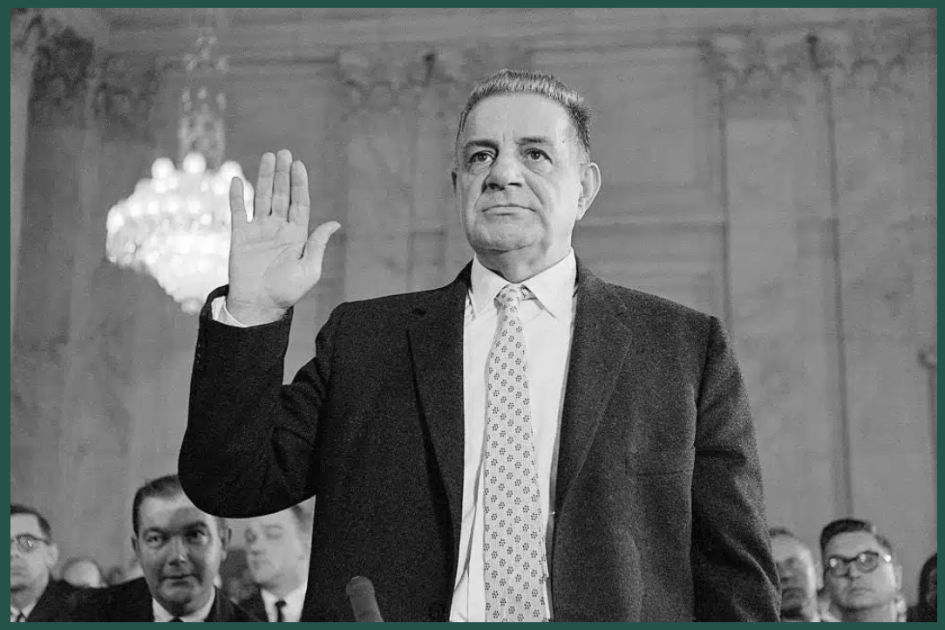

Frank Costello’s hands filled the television screen. The rest of him was off-camera—a compromise between his lawyers and the Kefauver Committee. But those hands, fidgeting and gesturing as he invoked the Fifth Amendment dozens of times, became one of the most unsettling images in early television history.

The year was 1951. Millions of Americans watched a mob boss legally refuse to answer questions about organized crime. The Fifth Amendment was doing exactly what the Framers intended—protecting someone from government-compelled self-incrimination. The public reaction was visceral: if he’s innocent, why won’t he talk?

That tension—between constitutional protection and public perception—has defined the Fifth Amendment’s most controversial moments for seventy years.

#10: The Hollywood Ten and the Blacklist Era

The Fifth Amendment was written to prevent tyranny. In 1947, it couldn’t prevent careers from being destroyed.

Ten screenwriters and directors faced the House Un-American Activities Committee investigating Communist infiltration in Hollywood. Some refused to answer any questions on First Amendment grounds. Others invoked the Fifth to avoid self-incrimination about political affiliations.

All ten were cited for contempt. Most served prison time. All were blacklisted—unemployable in Hollywood for years. Their invoking constitutional rights became evidence of guilt in the court of public opinion.

The contradiction was stark: you have the right to remain silent, but exercising it may cost you everything. Dalton Trumbo wrote Oscar-winning screenplays under pseudonyms for a decade. Ring Lardner Jr. didn’t work openly in Hollywood again until 1965.

The tension: Does a constitutional right mean anything if using it destroys your livelihood?

#9: Paul Robeson’s Political Defiance

Paul Robeson wasn’t a criminal. He was a civil rights icon, acclaimed actor, and activist who spoke out against racism and imperialism. When he appeared before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956, he used the Fifth Amendment not to hide crimes but to resist political persecution.

The hearing devolved into confrontation. Robeson challenged the committee’s authority and legitimacy while invoking his Fifth Amendment rights. His passport had already been revoked. His career was effectively over in the United States.

His case demonstrated something the Framers understood but modern audiences forget: the Fifth Amendment protects political dissent as much as it protects the accused. Robeson wasn’t hiding guilt—he was refusing to participate in what he considered an illegitimate inquisition.

The tension: When does the Fifth Amendment protect conscience rather than crime?

#8: Enron Executives and the Corporate Shield

Jeffrey Skilling and Andrew Fastow watched Enron collapse in 2001, taking $74 billion in shareholder value and thousands of employees’ retirement savings with it. When congressional hearings began, senior executives pleaded the Fifth en masse.

The legal strategy was sound—anything they said could be used in criminal prosecutions. The optics were catastrophic. Americans watched executives who’d profited from fraud invoke constitutional protections while their victims lost everything.

Skilling was eventually convicted and sentenced to 24 years (later reduced to 14). Fastow pleaded guilty and cooperated. But the image of wealthy executives hiding behind the Fifth Amendment while ordinary people suffered became a symbol of corporate impunity.

The tension: Do constitutional rights protect the powerful more effectively than the powerless?

#7: 2008 Financial Crisis CEOs

Banking executives appeared before Congress after the 2008 financial crisis that triggered the Great Recession. Some testified. Others invoked Fifth Amendment rights or declined to appear. Very few faced criminal prosecution.

The public watched financial industry leaders whose decisions had devastated the economy use constitutional protections to avoid accountability. Meanwhile, millions of Americans lost homes, jobs, and savings.

Legal scholars noted the difficulty of proving criminal intent in complex financial transactions. Critics argued that if ordinary people caused equivalent damage through fraud, prosecutors would find a way to charge them.

The Fifth Amendment worked exactly as designed—protecting individuals from compelled self-incrimination. It just happened to protect people whose actions had triggered economic catastrophe.

The tension: Does the Fifth Amendment create different outcomes for white-collar crime than street crime?

#6: Susan McDougal and Whitewater

Susan McDougal spent 18 months in jail for refusing to testify before a grand jury investigating Bill and Hillary Clinton’s Whitewater real estate investments. She invoked her Fifth Amendment rights and was held in civil contempt.

McDougal argued independent counsel Kenneth Starr was pursuing a political vendetta and that any testimony would be twisted against the Clintons. She chose jail over cooperation. Public reaction split sharply along partisan lines—heroic resistance or obstruction of justice, depending on your politics.

She was eventually acquitted of obstruction charges. President Clinton pardoned her on his last day in office for earlier Whitewater-related convictions. The case demonstrated how the Fifth Amendment becomes a weapon in political warfare—one side’s constitutional protection is the other side’s proof of conspiracy.

The tension: Is silence noble resistance or calculated obstruction?

#5: John Dean’s Strategic Silence

John Dean initially invoked the Fifth Amendment during Watergate investigations. As White House Counsel, he knew where all the bodies were buried—literally and figuratively.

Then he flipped. Dean became the prosecution’s star witness, testifying for days about President Nixon’s involvement in the cover-up. His testimony helped bring down a presidency.

The sequence matters: Dean used the Fifth Amendment as a strategic pause while deciding whether to cooperate. It wasn’t admission of guilt or permanent silence—it was legal maneuvering while his lawyers negotiated immunity.

His case demonstrates what lawyers know but the public often misses: pleading the Fifth can be the first move in cooperation, not the last move of the guilty.

The tension: The Fifth Amendment as tactic versus the Fifth Amendment as principle.

#4: Nixon Administration Officials En Masse

Multiple Nixon administration officials invoked the Fifth Amendment during Senate Watergate hearings. The pattern became obvious: high-ranking officials refusing to answer questions on live television about presidential corruption.

H.R. Haldeman, John Ehrlichman, and other senior aides all used Fifth Amendment protections at various points. The hearings were televised. Americans watched the executive branch hide behind constitutional rights while the presidency imploded.

The optics were devastating. Public trust in government cratered. The Fifth Amendment became synonymous with government secrecy and abuse of power—the opposite of what the Framers intended.

Nixon himself never invoked the Fifth. He resigned before impeachment. But his subordinates’ repeated invocations created the impression of systemic corruption protected by constitutional loopholes.

The tension: When constitutional protections enable cover-ups rather than prevent tyranny.

#3: Michael Flynn’s Partisan Lightning Rod

Former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn invoked the Fifth Amendment during congressional investigations into Russian interference in the 2016 election. The decision triggered immediate partisan warfare.

Critics noted Flynn had once said “when you are given immunity, that means you probably committed a crime.” Flynn’s lawyers argued he faced a “perjury trap” where any testimony could be used against him regardless of truthfulness.

Flynn eventually pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI about contacts with Russian officials, then withdrew the plea, then was pardoned by President Trump. The legal saga became entirely subsumed by partisan politics—each side interpreting the Fifth Amendment invocation as proof of their narrative.

The tension: Constitutional rights disappear into political tribalism.

#2: Trump’s “Only the Mob” Reversal

In 2016, Donald Trump said: “The mob takes the Fifth Amendment. If you’re innocent, why are you taking the Fifth Amendment?”

In 2022, he invoked the Fifth Amendment over 440 times during a New York civil deposition related to his business practices. His statement explaining the decision cited “unfair” prosecution and political bias.

The reversal was instant fodder for critics citing hypocrisy. Trump’s defenders argued he was correct about political prosecution and smart to use available protections. Legal scholars noted that civil depositions allow adverse inferences from Fifth Amendment invocations—unlike criminal trials.

The episode crystallized how the Fifth Amendment functions in modern American discourse: a constitutional right that everyone supports in theory until someone they dislike uses it, at which point it becomes evidence of guilt.

The tension: Principles versus partisanship in constitutional rights.

#1: Vito Genovese and the Mob’s Constitutional Strategy

Vito Genovese perfected what Frank Costello started—using the Fifth Amendment as standard operating procedure for organized crime. Throughout the 1950s, mafia figures invoked the Fifth so routinely it became part of mob culture.

Genovese and dozens of other organized crime figures appeared before congressional committees and refused to answer hundreds of questions. The hearings were public spectacles. Senators expressed outrage. Editorial writers condemned constitutional protections that seemed designed for criminals.

The public association became permanent: pleading the Fifth equals guilt. Innocent people don’t hide. If you have nothing to fear, you have nothing to hide. The mob’s enthusiastic embrace of the Fifth Amendment poisoned public perception for generations.

Legal scholars noted the bitter irony—the Fifth Amendment was working exactly as intended, protecting individuals from government overreach. It just happened to protect actual criminals, which made Americans question whether the protection should exist at all.

The tension: The Fifth Amendment may be most important when it’s most uncomfortable.

The Gap Between Law and Perception

The Fifth Amendment’s text is straightforward: “No person shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.” The Supreme Court has consistently held that invoking it cannot be used as evidence of guilt in criminal trials.

But constitutional law and human psychology operate differently. Study after study shows that most Americans assume Fifth Amendment invocations indicate guilt. Jurors in civil cases, where adverse inferences are permitted, almost universally interpret silence as admission.

The gap creates a constitutional paradox. You have the right to remain silent. Exercising it may destroy you anyway—not legally, but socially, professionally, reputationally.

Why the Powerful Use It More

The Fifth Amendment protects everyone equally under law. In practice, it protects the powerful more effectively.

Wealthy defendants can hire lawyers who know when to invoke it strategically. They can afford to fight contempt charges. They can withstand reputational damage better than ordinary people who need employment references and community standing.

Organized crime figures in the 1950s had nothing to lose—their reputations were already criminal. Corporate executives can invoke it and retire comfortably. Politicians can invoke it and fundraise off persecution narratives.

An ordinary person invoking the Fifth Amendment in a workplace investigation gets fired. A CEO invoking it before Congress gets a legal defense fund and a book deal. Same constitutional right, radically different outcomes.

Civil Versus Criminal: When Silence Speaks

The Fifth Amendment applies differently in civil and criminal contexts. Criminal juries cannot draw negative inferences from a defendant’s silence. Civil juries can.

That distinction matters enormously. In criminal cases, the protection works as designed. In civil cases, it becomes a calculated risk—invoke the Fifth and the jury assumes you’re hiding guilt, or testify and potentially provide ammunition for criminal prosecution.

Trump’s New York deposition illustrated the dilemma perfectly. Invoke the Fifth 440 times and face public ridicule and adverse civil judgments, or testify and create criminal exposure. There’s no good option—only less-bad choices.

The Framers designed the Fifth Amendment for criminal prosecutions. They couldn’t have anticipated modern civil litigation where the same conduct triggers parallel proceedings with different constitutional protections.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The Fifth Amendment was written to prevent torture, forced confessions, and tyrannical government power. The Framers witnessed English monarchs compelling self-incrimination through brutality. They created a constitutional barrier: the government must prove guilt without forcing the accused to help.

It’s one of America’s most important freedoms. It’s also most famous for protecting mobsters, corrupt officials, corporate executives, and politicians accused of wrongdoing.

That’s not a flaw—it’s the design. Constitutional rights must protect unpopular people in uncomfortable situations, or they’re not rights at all. The Fifth Amendment only matters when invoking it looks bad.

But history reveals the cost of that design. Every high-profile Fifth Amendment invocation strengthens public perception that silence equals guilt. Every mob boss who successfully stonewalls Congress convinces more Americans that constitutional protections benefit criminals.

The tension is inherent and unresolvable. We want constitutional rights that protect the innocent. We’re frustrated when they protect the guilty. The Fifth Amendment does both—and we can’t separate them.