For 217 years, the Second Amendment didn’t protect your right to own a gun for self-defense in your home.

Then in 2008, it suddenly did.

The Supreme Court’s decision in District of Columbia v. Heller declared for the first time in American history that the Constitution guarantees an individual right to possess firearms unconnected to militia service. The 5-4 ruling struck down Washington D.C.’s handgun ban and fundamentally rewrote how courts evaluate gun regulations.

Whether that decision restored the Framers’ original intent or invented a constitutional right that never existed is the most consequential interpretive dispute in modern Second Amendment law. The answer determines whether gun rights are being protected or whether they’re being created by judges imposing their policy preferences under the guise of constitutional interpretation.

The stakes go far beyond guns. If the Supreme Court can “discover” new rights in 217-year-old text that previous generations of judges somehow missed, then constitutional meaning becomes whatever five justices say it is.

What Courts Said Before 2008

Before Heller, federal courts overwhelmingly treated the Second Amendment as connected to militia service, not individual self-defense. Lower courts routinely upheld gun regulations with minimal constitutional scrutiny. The Supreme Court itself had barely touched the issue since United States v. Miller in 1939.

Miller involved a prosecution under the National Firearms Act for possessing a sawed-off shotgun. The Court upheld the conviction, noting that the weapon had no “reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.” The decision suggested the Second Amendment protected only weapons useful for militia purposes.

For nearly 70 years after Miller, that’s how courts interpreted the Amendment. The “well regulated Militia” language in the prefatory clause wasn’t decorative – it defined the scope of the right. State and federal governments could regulate firearms as long as regulations didn’t interfere with organized militia readiness.

This wasn’t a fringe interpretation. It was the dominant legal understanding taught in law schools, applied by circuit courts, and reflected in federal government briefs. Gun regulations proliferated without serious constitutional challenge. The Second Amendment was treated as one of the weakest rights in the Bill of Rights.

Then Heller arrived and declared that entire framework wrong.

The Textual Argument That Changed Everything

Justice Antonin Scalia’s majority opinion in Heller rested on a simple textual observation: the Second Amendment says “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

The phrase “the right of the people” appears in the First, Fourth, and Ninth Amendments. In every other instance, it refers to individual rights, not collective or governmental powers. The First Amendment protects “the right of the people peaceably to assemble.” The Fourth protects “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects.”

No one argues those amendments protect state governments rather than individuals. Scalia argued the Second Amendment should be read the same way – as protecting an individual right that exists independent of militia service.

The prefatory clause about a “well regulated Militia” announces a purpose but doesn’t limit the operative clause. It explains why the right exists, not who holds it. Colonial Americans needed firearms for self-defense and to serve in militias if called upon. The Amendment protects the underlying individual right that makes militia service possible.

This textual argument is straightforward and internally consistent. The problem is that it requires concluding that federal courts got the Second Amendment wrong for two centuries.

The Historical Sources That Support Individual Rights

Heller didn’t just rely on text. Scalia marshaled extensive historical evidence that the Founding generation understood firearm ownership as an individual right.

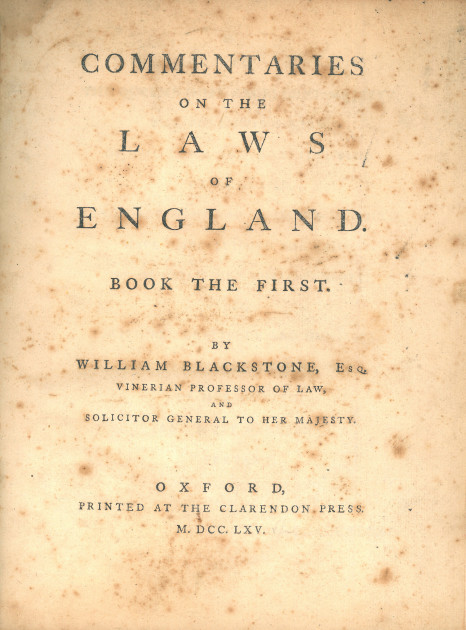

English common law recognized a right to arms for self-defense dating back to the 1689 English Bill of Rights. Blackstone’s Commentaries – the most influential legal text in early America – described the right to have arms as one of the “absolute rights of individuals.”

Early state constitutions protected gun rights in explicitly individual terms. Pennsylvania’s 1776 constitution declared “the people have a right to bear arms for the defence of themselves and the state.” Vermont, Massachusetts, and other states adopted similar language emphasizing personal self-defense alongside collective security.

Founding-era discussions of the Second Amendment in Congress and ratifying conventions referenced both militia service and individual protection. Madison’s original draft referred to “the right of the people to keep and bear arms” without limiting it to militia contexts. The language that became the Second Amendment preserved that individual phrasing.

If the Framers intended to protect only a collective militia right, this evidence suggests they chose remarkably poor language to express that intent. Every textual and historical marker points toward individual ownership, not governmental armories.

Why Critics Say This History Is Selective

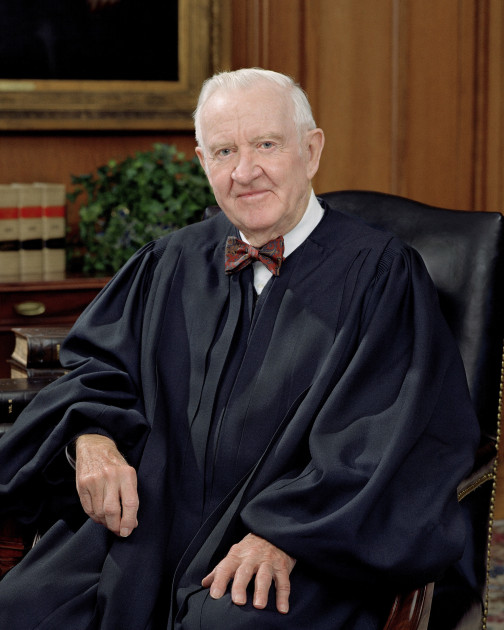

Justice Stevens’ dissent in Heller argued that Scalia’s history was cherry-picked to support a predetermined conclusion while ignoring contrary evidence.

The Amendment’s text doesn’t just mention “the people” – it specifically references “a well regulated Militia” as the purpose for the right. That prefatory clause isn’t decorative. It’s part of the constitutional text that must be given meaning.

Colonial-era gun ownership was universal not because of an individual self-defense right, but because all able-bodied men were expected to serve in militias and needed to bring their own weapons. The right protected personal ownership for militia purposes, not general self-defense divorced from collective security.

Early militia laws often required gun ownership, allowed inspections to ensure weapons were functional, and even mandated specific types of firearms. This regulatory framework is inconsistent with the robust individual right Heller recognized. If the Framers intended to prevent gun regulations, they wouldn’t have simultaneously enacted extensive regulations themselves.

Stevens pointed out that for 200 years, no federal court struck down a gun law based on the Second Amendment. During that entire period, states and the federal government heavily regulated firearms – banning concealed carry, restricting dangerous weapons, requiring licensing. If Heller’s interpretation was correct, those regulations should have triggered constitutional challenges. They didn’t, because no one thought the Second Amendment prohibited them.

The Precedent Problem

Heller didn’t just contradict academic consensus – it overturned how lower federal courts had been deciding Second Amendment cases for decades.

Multiple circuit courts had explicitly held that the Second Amendment protects only militia-related rights, not individual self-defense. The Ninth Circuit called it a “collective right.” The Seventh Circuit said it “protects only such acts of firearms possession as are reasonably related to the preservation of the militia.”

Those weren’t aberrations. They reflected the mainstream judicial understanding of Miller and Second Amendment history. When Heller declared that understanding wrong, it wasn’t clarifying ambiguous precedent – it was reversing settled law that had guided courts for generations.

Justice Stevens wrote that the majority was “rejecting a consensus view shared by every federal court of appeals.” That’s not interpretation. That’s rewriting.

Supporters respond that lower courts were simply wrong, and the Supreme Court corrected a longstanding error. But that response concedes the key point: Heller changed the law. The question is whether that change restored the Constitution’s original meaning or imposed a new one.

What Changed After Heller

Heller opened litigation floodgates. Suddenly, every gun regulation faced potential constitutional challenges under a newly enforceable individual right.

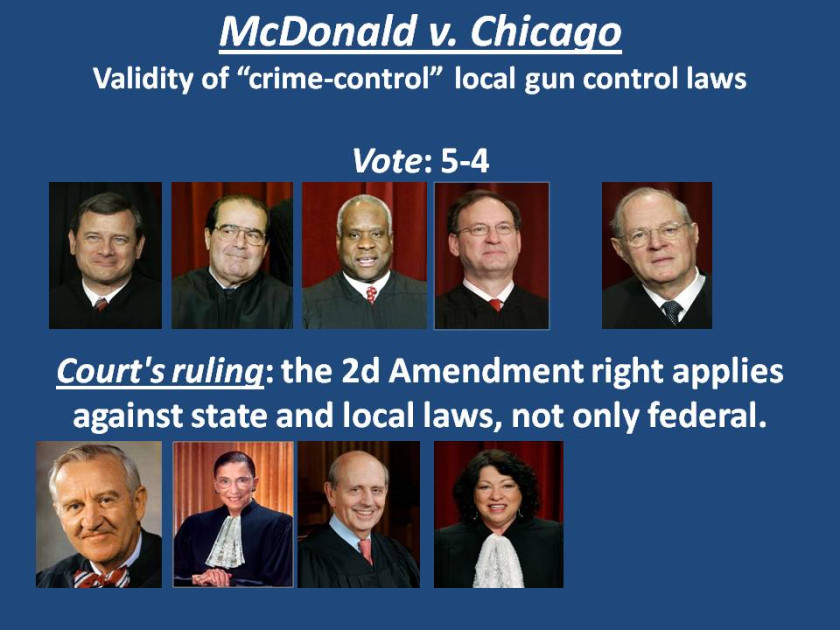

Two years later, McDonald v. Chicago (2010) incorporated the Second Amendment against state governments through the Fourteenth Amendment. That meant Heller’s individual right applied nationwide, not just in federal enclaves like Washington D.C.

Then New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022) went further, establishing that gun regulations must be “consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation” to survive constitutional scrutiny. Courts can’t just apply interest-balancing tests – they must find historical analogues showing the Founding generation would have permitted similar restrictions.

Bruen makes Heller’s historical methodology mandatory for all Second Amendment cases. If judges in 2008 “discovered” an individual right through historical analysis, judges in 2024 must discover the boundaries of that right through the same process.

The result is that modern gun policy gets filtered through 18th-century sources. Whether you can ban assault weapons depends on whether there’s a historical analogue from the 1790s. Whether you can require background checks depends on whether similar prerequisites existed in the Founding era.

The Broader Constitutional Question

Heller’s legitimacy problem isn’t unique to guns. It’s the central tension in originalist constitutional interpretation: If the original meaning is so clear, why did it take 200 years to enforce it?

One answer is that courts got it wrong for two centuries, and Heller finally corrected the mistake. That answer preserves originalism but requires accepting that multiple generations of judges, scholars, and legislators completely misunderstood a constitutional provision that’s only 27 words long.

The other answer is that Heller imposed a modern ideological preference disguised as historical interpretation. The historical sources are ambiguous enough to support multiple readings. Scalia chose the reading that aligned with conservative policy preferences about gun rights, then declared it the only legitimate interpretation.

This debate extends beyond the Second Amendment. If courts can “discover” that the Framers intended to protect individual gun rights despite 200 years of precedent saying otherwise, they can discover anything. Privacy rights that aren’t in the text. Marriage rights the Founders never contemplated. Or – as Dobbs demonstrated – the absence of rights that previous Courts thought they’d found.

The Constitution becomes whatever the current Court majority says the Framers would have meant if they’d been asked questions the Framers never considered.

What Heller Actually Says About Constitutional Interpretation

Heller explicitly acknowledged that gun rights aren’t unlimited. The Court said “longstanding prohibitions” on firearm possession by felons and the mentally ill remain constitutional. So do restrictions on carrying guns in “sensitive places” like schools and government buildings.

The decision tried to thread a needle: recognize an individual right while preserving reasonable regulations. But it didn’t explain how to distinguish constitutional regulations from unconstitutional ones beyond saying that total bans fail and modest regulations might survive.

That ambiguity has generated endless litigation. Every regulation now faces the question: Is this a “longstanding” exception Heller blessed, or an unconstitutional infringement on the individual right Heller recognized?

Bruen tried to answer that question by requiring historical analogues. But that just shifts the debate to which historical regulations count as analogues and how similar they must be to modern laws. Courts now argue about whether 18th-century gunpowder storage laws justify 21st-century ammunition regulations.

The textual and historical method Heller pioneered hasn’t produced clarity. It’s produced more litigation, more judicial discretion in selecting which historical sources matter, and more policy-making by judges claiming they’re just following the Framers’ intent.

Did the Court Invent a Right or Restore One?

The answer determines whether Heller represents constitutional interpretation or judicial activism masquerading as history.

If you believe constitutional meaning is fixed at ratification, and the Framers clearly intended to protect individual gun ownership, then Heller corrected 200 years of judicial error. The right always existed – courts just refused to enforce it until 2008.

If you believe constitutional meaning evolves through precedent and practice, and two centuries of gun regulations without constitutional resistance demonstrates what the Second Amendment actually permits, then Heller invented a new right by cherry-picking historical sources that support a predetermined conclusion.

Both sides claim fidelity to the Constitution. Both sides accuse the other of imposing ideological preferences through selective interpretation. Neither can prove their reading is objectively correct because constitutional text doesn’t come with an instruction manual.

The Framers wrote “the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” They didn’t specify whether that meant individuals or militias, self-defense or collective security, handguns in homes or muskets in armories. They left 27 words that have generated centuries of debate about what they were trying to protect.

Heller chose one answer and declared it definitive. Whether that answer reflects the Framers’ intent or Justice Scalia’s preference is the question that will define Second Amendment law for generations.

Why This Matters Beyond Guns

Constitutional rights that exist only because courts recently discovered them are vulnerable to being un-discovered by future courts with different interpretive commitments.

Heller demonstrated that 200 years of contrary precedent won’t prevent the Supreme Court from recognizing new rights if five justices believe the text and history support them. Dobbs demonstrated that 50 years of precedent won’t prevent the Court from eliminating rights if five justices believe they were wrongly decided.

The pattern is clear: constitutional rights depend less on what the text says or what precedent held than on how current justices interpret ambiguous historical sources. That makes every right contingent on judicial appointments and interpretive methodology.

If Heller invented a gun right in 2008, then Griswold invented a privacy right in 1965, Obergefell invented a same-sex marriage right in 2015, and Roe invented an abortion right in 1973 that Dobbs un-invented in 2022. Rights become whatever judges say they are, backed by whichever historical sources judges find persuasive.

The alternative is accepting that courts sometimes get constitutional meaning wrong for extended periods, and later Courts correct those errors through better interpretation. But that alternative requires explaining why Heller corrected an error while Dobbs created one, or vice versa, without just saying “I agree with the outcome I like.”

The Right That Didn’t Exist Until It Did

The Second Amendment was ratified in 1791. For 217 years, no federal court struck down a gun law based on an individual right to armed self-defense. Then in 2008, the Supreme Court said that right had existed all along – courts just hadn’t been enforcing it.

Whether Heller discovered or invented that right depends on questions that can’t be answered definitively: What did the Framers intend? How much does historical practice matter? Can courts correct longstanding errors, or are they just imposing new meanings?

The one indisputable fact is that gun rights in 2025 look nothing like they did in 2007. Regulations that were constitutional before Heller are now subject to rigorous scrutiny. Rights that weren’t enforceable are now fundamental. Courts that deferred to legislatures now second-guess policy choices through historical analysis.

That transformation happened because five Supreme Court justices read the Second Amendment differently than previous generations had. Whether that reading reflects the Constitution’s true meaning or just reflects how those five justices think constitutional law should work is the question that will haunt Second Amendment jurisprudence for as long as Heller remains good law.

The gun right that didn’t exist until 2008 is now one of the most protected rights in American constitutional law. Critics call that judicial invention. Supporters call it constitutional restoration.

Both sides agree the Supreme Court changed everything. They just can’t agree on whether the Court was interpreting the Constitution or rewriting it.