Thirteen House Republicans defied their party leadership Wednesday night to advance a bill reversing President Trump’s executive order that stripped collective bargaining rights from federal worker unions.

The vote wasn’t supposed to happen. House Speaker Mike Johnson didn’t schedule it. Republican leadership opposed it. But Rep. Jared Golden, a Maine Democrat, forced the vote anyway using a procedural mechanism called a discharge petition – a rarely successful maneuver that bypasses leadership entirely if it gets majority support.

It worked. The motion to proceed passed 222-200, with all 209 voting Democrats joined by 13 Republicans. The bill now heads to a final House vote Thursday, where it could become one of the few discharge petitions in recent history to actually pass both procedural hurdles and reach the President’s desk.

The Republicans who voted yes weren’t random defectors. Most represent competitive districts in blue states where union support matters. Several have received union endorsements in previous campaigns. All of them are calculating that defying Trump on this issue is less dangerous than facing union-backed challengers in 2026.

The question is whether 13 Republicans breaking ranks signals a genuine institutional check on executive power, or just electoral self-preservation dressed up as principle.

What Trump’s Order Actually Did

In March 2025, Trump signed an executive order blocking collective bargaining rights for federal workers at multiple agencies – Defense, State, Veterans Affairs, Justice, Energy, Homeland Security, Treasury, Health and Human Services, Interior, and Agriculture.

The order didn’t eliminate federal unions entirely. It stripped their ability to negotiate over working conditions, grievance procedures, and workplace policies. Federal workers could still join unions, but those unions couldn’t bargain collectively on their behalf.

Trump framed the move as eliminating bureaucratic inefficiency and restoring management control. Federal employee unions called it union-busting through executive fiat. The legal authority came from the President’s broad power to direct executive branch operations and interpret federal labor law.

Golden’s bill – the Protect America’s Workforce Act – would reverse the order entirely, restoring collective bargaining rights that federal workers held before March. It’s a direct legislative override of presidential action, which is exactly what Congress is supposed to do when it disagrees with how the executive branch exercises delegated authority.

The constitutional design assumes Congress will check presidential overreach. What’s unusual here is that it’s happening with the President’s own party controlling the House.

Why Discharge Petitions Almost Never Work

Discharge petitions are designed to force votes on legislation that leadership refuses to schedule. They require 218 signatures – an absolute majority of the House – to succeed. Once you hit that threshold, the bill automatically comes to the floor regardless of what the Speaker wants.

The mechanism exists specifically to prevent leadership from indefinitely blocking legislation with broad support. But it almost never succeeds because most majority-party members won’t openly defy their own leadership. Signing a discharge petition is a public declaration that you trust your colleagues’ judgment more than your party leaders’.

Golden got five Republicans to sign the petition alongside 213 Democrats: Brian Fitzpatrick of Pennsylvania, Rob Bresnahan of Pennsylvania, Don Bacon of Nebraska, Mike Lawler of New York, and Nick LaLota of New York. That brought the total to 218 – exactly enough to force the vote.

When the actual vote happened Wednesday, eight more Republicans joined them. Jeff Van Drew of New Jersey, Nicole Malliotakis of New York, Tom Kean of New Jersey, Ryan Mackenzie of Pennsylvania, Zach Nunn of Iowa, Chris Smith of New Jersey, Pete Stauber of Minnesota, and Mike Turner of Ohio all voted to advance the bill despite not signing the discharge petition.

The pattern is clear: most of these districts are competitive, located in blue or purple states, or represent areas with significant union presence. These aren’t ideological moderates making a stand on principle. They’re vulnerable incumbents making a political calculation about which constituency matters more in 2026 – Trump’s base or union voters.

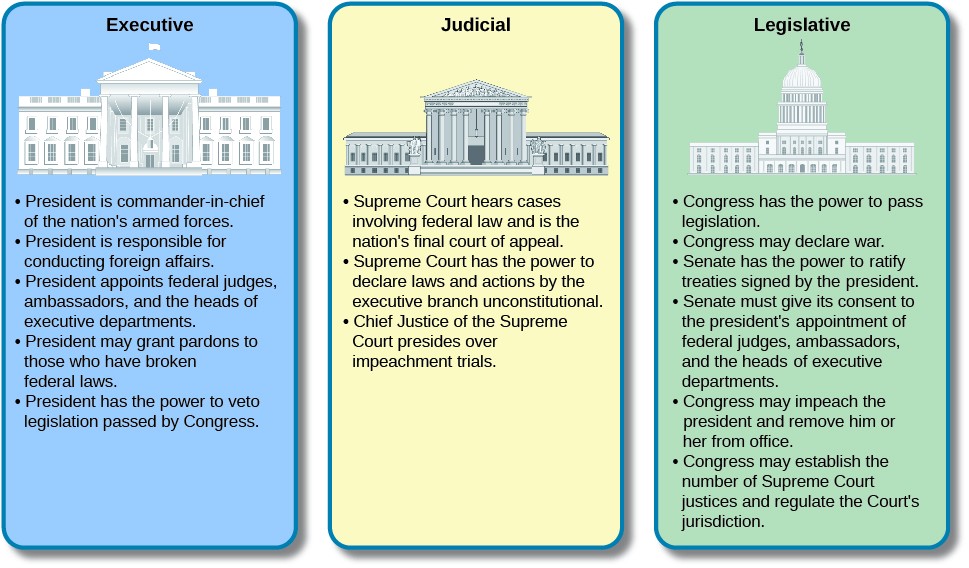

The Separation of Powers Question

Article I gives Congress the power to make laws. Article II gives the President the power to execute them. When Congress passes legislation governing federal labor relations, the President must enforce it. When the President uses executive authority to reshape federal labor policy, Congress can override that action through legislation.

That’s exactly what’s happening here. Trump used his executive power to restrict collective bargaining. Congress is now using its legislative power to restore it. If the bill passes both chambers and Trump vetoes it, Congress could override the veto with a two-thirds vote.

This is separation of powers functioning as designed – competing branches checking each other through their respective constitutional authorities. The Framers built the system precisely so that executive actions couldn’t go unchecked if Congress disagreed strongly enough to act.

The complication is that Congress is controlled by the President’s own party, which creates internal political pressure not to challenge executive actions even when they exceed what many members think is appropriate. The discharge petition mechanism forces the issue by allowing a cross-party majority to act even when party leadership would prefer to protect the President.

What Happens If This Actually Passes

If Golden’s bill survives Thursday’s rule vote and passes the full House, it goes to the Senate. Senate Republicans hold a narrow majority, which means Democrats would need several Republican votes to pass it there too.

The same electoral math applies: Republican senators in blue or purple states with union constituencies have to decide whether bucking Trump is worth the risk. Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Susan Collins of Maine, and potentially a few others could provide the necessary votes if they calculate that union support matters more than presidential loyalty.

If it passes the Senate, Trump would almost certainly veto it. He’s not going to sign legislation reversing his own executive order. That forces Congress to decide whether they can muster a two-thirds supermajority in both chambers to override the veto.

That’s unlikely. Overriding a presidential veto requires 67 Senate votes and 290 House votes. Even if every Democrat votes yes, you’d need 20 Senate Republicans and 72 House Republicans to break with Trump. The 13 House Republicans who voted to advance the bill represent less than 6% of the Republican caucus. Getting 72 would require a full-scale party revolt.

So the most likely outcome is that the bill passes the House, dies in the Senate or survives there but can’t override Trump’s veto, and federal workers lose their collective bargaining rights anyway. But the political message gets sent: there are Republicans willing to break with Trump on labor issues when their electoral survival depends on it.

The Broader Context on Executive Authority

Trump’s executive order is part of a larger pattern of presidents using unilateral authority to reshape policy when Congress won’t cooperate. Executive orders on immigration, environmental regulation, labor policy, and national security have become the default tool for accomplishing goals that can’t pass through legislation.

The Constitution doesn’t explicitly authorize executive orders. They derive from the President’s Article II power to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” and his role as chief executive. But that authority is supposed to be constrained by the laws Congress passes – the President executes the law, he doesn’t make it.

When presidents use executive orders to effectively rewrite policy Congress has already addressed through legislation, they’re testing the boundaries of executive power. Congress can push back through legislation overriding the order, funding restrictions, or judicial challenges arguing the order exceeds statutory authority.

The discharge petition forcing a vote on Golden’s bill is Congress asserting its legislative authority against executive policymaking. Whether it ultimately succeeds matters less than the fact that a bipartisan majority forced the vote at all.

What the Vote Reveals About Republican Unity

The GOP’s razor-thin House majority – they can only lose two votes on party-line measures – has made every controversial issue a potential defection opportunity. When 13 Republicans break ranks on a high-profile vote, it signals that party discipline is breaking down on issues where members face conflicting pressure from Trump’s base and their home districts.

Federal worker unions aren’t a major Republican constituency. But several of the Republicans who voted yes represent districts with significant federal employment – defense contractors, VA facilities, DHS personnel. Stripping those workers’ collective bargaining rights creates local political problems that abstract conservative principles about limiting union power don’t solve.

The vote also reveals which Republicans think they’re vulnerable enough in 2026 that they need to build cross-party coalitions now. Lawler, LaLota, and Malliotakis all represent New York districts that Biden won in 2020. Fitzpatrick’s Pennsylvania district is competitive. These aren’t safe Republican seats where loyalty to Trump guarantees reelection.

The members who defied leadership are betting that their political survival depends on demonstrating independence from Trump on specific issues that matter locally. That calculation only works if voters actually reward moderation and bipartisanship, which isn’t guaranteed in an increasingly polarized electorate.

The Institutional Check That Might Not Matter

Discharge petitions exist specifically to prevent leadership from unilaterally controlling the House agenda. The fact that one succeeded here demonstrates that the mechanism can still work when enough members prioritize an issue over party loyalty.

But the practical impact is limited if the legislation dies in the Senate or gets vetoed and Congress can’t override. The constitutional system of checks and balances only functions if the checking actually constrains the behavior being checked.

If Trump’s executive order remains in effect despite a House vote repealing it, then Congress’s legislative power didn’t actually check executive authority – it just registered disagreement that the President ignored. The check only matters if it changes the outcome.

The Framers assumed that Congress would jealously guard its prerogatives and resist executive encroachment. What they didn’t fully anticipate was party loyalty creating situations where congressional majorities would defer to executive power when their own party controls the presidency.

Thirteen Republicans breaking ranks isn’t a systemic failure of that dynamic. It’s a reminder that electoral pressure can sometimes override partisan loyalty – but only when members think their political survival depends on it.

The discharge petition worked. Whether the constitutional check it represents actually constrains presidential power depends on what happens next in the Senate and whether Congress can override a veto. If it can’t, then the vote becomes a symbolic gesture rather than a meaningful institutional constraint.

But symbolic gestures matter too. They establish that some Republicans will break with Trump when the political cost of loyalty becomes too high. That’s not robust institutional independence. But in a system increasingly dominated by party discipline and executive unilateralism, even modest defection is worth noting.

The question is whether 13 Republicans voting to restore union rights represents a genuine check on executive overreach, or just 13 incumbents making the minimum political calculation necessary to survive their next election.

The answer probably depends on how many of them are still in Congress after 2026.