President Trump signed a Columbus Day proclamation Thursday, and his Cabinet spontaneously broke into applause as he declared “We’re back, Italians.” It was a small moment with big symbolic weight – Trump explicitly rejecting the progressive shift toward Indigenous Peoples’ Day and reasserting federal recognition of the Italian explorer who sailed across the Atlantic in 1492.

The applause itself became part of the story, with Trump joking that even the press corps clapped, though he was likely referring to White House staff. But underneath the ceremony and the culture war theatrics lies an actual constitutional question: what power do presidential proclamations have, and can a president simply overrule previous administrations’ decisions about what federal holidays mean?

At a Glance

- Trump signed a Columbus Day proclamation Thursday ahead of the federal holiday Monday, October 13

- Cabinet members and White House staff applauded as Trump declared “We’re back, Italians”

- Columbus Day has been a federal holiday since 1971, but recent administrations also recognized Indigenous Peoples’ Day

- Trump also signed a proclamation honoring Viking explorer Leif Erikson, credited as the first European to reach North America

- At stake: whether presidential proclamations can settle culture war debates about American history

The Proclamation Ceremony

White House Staff Secretary Will Scharf set up the moment by explaining Columbus’s historical significance: “Columbus, obviously, discovered the new world in 1492. He was a great Italian explorer. He sailed his three ships, the Nina, the Pinto and Santa Maria, across the Atlantic Ocean, and landed in what’s today the Caribbean.”

Scharf emphasized that “this is a particularly important holiday for Italian Americans who celebrate the legacy of Christopher Columbus, and the innovation and explorer zeal that he represented.”

When Trump added “In other words, we’re calling it Columbus Day,” the room erupted in applause. Trump continued: “We’re back, Italians,” drawing more applause before quipping that even the press broke out in applause – “I’ve never seen that happen.”

“Columbus Day. We’re back. Columbus Day. We’re back, Italians. We love the Italians.” – President Donald Trump

The ceremony was clearly designed as a culture war statement, explicitly rejecting the progressive push to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day. But it also represents something more fundamental about presidential power and symbolism.

The Constitutional Authority Behind Proclamations

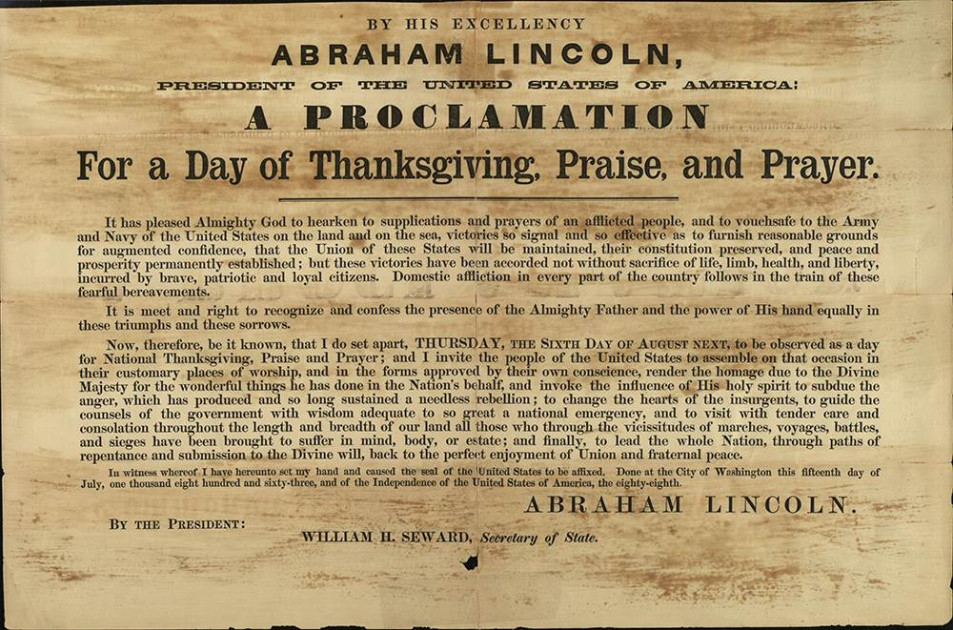

Presidential proclamations are interesting constitutional creatures. They’re official statements issued by the President, but they don’t have the force of law unless Congress has granted specific statutory authority. Columbus Day became a federal holiday through an act of Congress in 1971, following decades of Italian American advocacy and previous presidential proclamations recognizing the holiday.

Since Congress made Columbus Day a federal holiday, the President can’t unilaterally eliminate it. But presidents have broad discretion in how they characterize federal holidays through their annual proclamations. Recent administrations – particularly Obama and Biden – issued dual proclamations recognizing both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

Trump is exercising his authority to define how the federal government officially recognizes the holiday. His proclamation doesn’t change the legal status of Columbus Day as a federal holiday (that would require Congress), but it does signal the administration’s official position on what the day represents.

That symbolic power matters. Presidential proclamations shape public discourse, influence how federal agencies observe holidays, and send messages about what the administration values. Trump’s proclamation explicitly rejects the progressive narrative that Columbus represents colonialism and genocide, instead celebrating him as representing “innovation and explorer zeal.”

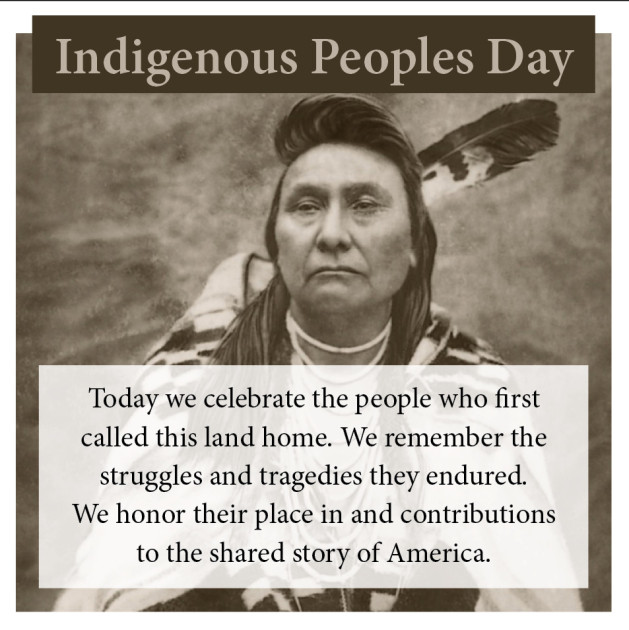

The Indigenous Peoples’ Day Movement

The push to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day gained momentum in recent years, driven by activists who argue Columbus’s arrival initiated centuries of violence, displacement, and disease that devastated Native American populations. Cities and states across the country have officially adopted Indigenous Peoples’ Day, and activists worked to remove Columbus statues – including toppling several during 2020 protests.

Vice President Kamala Harris was among political leaders who supported the shift. In 2021, she said: “Those explorers ushered in a wave of devastation for Tribal nations – perpetrating violence, stealing land and spreading disease. We must not shy away from this shameful past, and we must shed light on it and do everything we can to address the impact of the past on Native communities today.”

Biden’s proclamations recognized both Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day, attempting to honor Italian American heritage while acknowledging Native American history. Trump’s approach is different – he’s explicitly choosing Columbus over Indigenous Peoples’ Day, making it a binary choice rather than attempting to recognize both.

The debate over Columbus Day versus Indigenous Peoples’ Day is fundamentally about whose version of American history the federal government officially endorses.

The Leif Erikson Addition

Trump also signed a proclamation Thursday honoring Viking explorer Leif Erikson on October 9. Erikson is credited with discovering the coast of Newfoundland in Canada more than 1,000 years ago and is considered the first European to step foot on North America – roughly 500 years before Columbus.

The Erikson proclamation is less controversial because it doesn’t directly compete with Indigenous Peoples’ Day in the same way Columbus Day does. But it’s interesting that Trump chose to highlight Erikson’s earlier “discovery” while also celebrating Columbus. It suggests the administration is comfortable with a European-centric narrative of American history that emphasizes exploration and discovery rather than indigenous presence and colonization’s costs.

Erikson Day has been recognized by presidents since the 1960s and has strong support from Norwegian American and Scandinavian American communities. Unlike Columbus Day, it hasn’t become a major culture war flashpoint, possibly because Erikson’s voyages didn’t lead to immediate colonization and large-scale contact with indigenous peoples.

The Italian American Dimension

Columbus Day became a federal holiday largely due to decades of advocacy by Italian American organizations who saw Columbus as a symbol of Italian contributions to American history. For many Italian Americans, especially those whose families immigrated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries facing discrimination, Columbus Day represented recognition and acceptance in American society.

When Trump says “We’re back, Italians,” he’s speaking to that constituency and signaling that his administration views Columbus Day through the lens of Italian American heritage rather than indigenous history. It’s identity politics – just not the kind progressives typically champion.

The irony is that Columbus himself never set foot in what’s now the United States, and he wasn’t trying to prove the Earth was round (educated people already knew that). His voyages were funded by Spain, not Italy, which didn’t exist as a unified nation until the 19th century. But symbols matter more than historical precision in these debates, and for Italian Americans, Columbus represents something important about their community’s place in American history.

What the Founders Would Say

The Founders didn’t create federal holidays or presidential proclamations about historical commemorations – those traditions developed later. But they did care deeply about how American history would be told and what values would be celebrated.

Jefferson would probably question why we’re celebrating any European explorer given his concerns about European influence on American development. He’d likely prefer focusing on American achievements rather than celebrating people who came before the nation’s founding.

Hamilton might see Columbus Day as useful civic mythology that helps bind diverse immigrant communities to American identity. He understood the value of symbols and stories in creating national cohesion.

Madison would probably argue that questions about federal holidays should be resolved by Congress, not presidential proclamations. He’d view Trump’s approach as another example of executive overreach into areas that should be legislative decisions.

But none of them would recognize the modern culture war where federal holiday proclamations become battlegrounds over competing narratives of American history. They assumed shared civic values and common understanding of American identity in ways that no longer exist.

The Limits of Presidential Symbolism

Trump’s Columbus Day proclamation can’t force states and cities to stop recognizing Indigenous Peoples’ Day. It can’t restore toppled Columbus statues or change school curricula that teach about colonization’s impacts on indigenous peoples. It can’t resolve the underlying historical debates about Columbus’s legacy.

What it can do is signal federal priorities, influence how federal agencies observe the holiday, and give political validation to those who support traditional Columbus Day celebrations. It’s symbolic politics – but symbols have power, especially when issued by the President.

Presidential proclamations don’t have the force of law, but they have the force of presidential authority – and in polarized times, that matters.

The Cabinet’s spontaneous applause reveals how charged these symbolic battles have become. A routine presidential proclamation about a federal holiday that’s existed since 1971 became a moment of celebration precisely because it rejected progressive narratives about American history.

That’s where we are constitutionally: presidential authority to issue proclamations about federal holidays has become a tool in culture war battles over whose version of history gets official government endorsement.

The Broader Context

Trump has consistently positioned himself against what he calls “woke” reinterpretations of American history. He’s fought against critical race theory in federal training, opposed the 1619 Project’s framing of American history, and recently said American history won’t be displayed “in a woke manner” at the Smithsonian.

The Columbus Day proclamation fits this pattern. It’s Trump asserting that the federal government under his leadership will celebrate traditional narratives of American history emphasizing exploration, discovery, and progress rather than focusing on colonization’s costs to indigenous peoples.

Whether you view this as defending important traditions or refusing to acknowledge historical harms probably depends on your broader views about American history and identity. But constitutionally, the question is straightforward: presidents have authority to issue proclamations characterizing federal holidays however they choose, within the bounds of what Congress has established.

Trump exercised that authority Thursday, his Cabinet applauded, and for at least the next few years, the federal government will officially celebrate Columbus Day as honoring “the innovation and explorer zeal” of an Italian explorer who sailed across the Atlantic in 1492.

The constitutional system allows this. Whether it’s wise policy or good history is a different question entirely – one that presidential proclamations can influence but never settle.