Americans often worry about the stability of the next election. But our constitutional system has already been tested by electoral chaos four separate times in its history, pushing the nation to the very brink.

These are not just dusty stories from a history book. They are urgent lessons in how the Constitution’s guardrails have been used, and how they have sometimes bent – and nearly broken – under the immense pressure of a disputed transfer of power.

Each crisis reveals a deep truth about the resilience, and the profound fragility, of the American experiment.

At a Glance: Four Electoral Crises

- The Election of 1800: A flaw in the Constitution’s original design led to a tie between a presidential candidate and his own running mate, forcing a hostile House of Representatives to decide the winner.

- The Election of 1824: No candidate won an Electoral College majority, leading to a “Corrupt Bargain” in the House that many believed thwarted the will of the people.

- The Election of 1876: Widespread fraud and voter intimidation left the winner uncertain, forcing Congress to create a special commission that ultimately ended Reconstruction in a backroom political deal.

- The Election of 2000: For the first time, the Supreme Court directly intervened to halt a recount in a single state, effectively deciding the presidency.

The Election of 1800: A Constitutional Flaw and a Bloodless Revolution

The first great electoral crisis was a direct result of the Founders’ own miscalculation. The original Constitution did not distinguish between votes for President and Vice President. Each elector cast two votes, with the winner becoming President and the runner-up becoming Vice President.

The Crisis: In 1800, this led to a disaster. Democratic-Republican electors dutifully cast their two votes for their party’s ticket: Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. The result was a perfect tie, 73-73. The system had no way to determine who was intended for the top job.

The Constitutional Mechanism: As required by the Constitution, the tie was thrown to the House of Representatives for a contingent election. But there was a terrifying twist: the vote would be controlled by the lame-duck Federalist party, the very party Jefferson had just defeated. The Federalists were now in the position of choosing between the man they despised (Jefferson) and the man they viewed as an unprincipled opportunist (Burr).

The Resolution & Legacy: After 36 contentious ballots and fears of a potential civil war, the House finally elected Jefferson. The crisis was so severe that it led directly to the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804, which corrected the flaw by requiring electors to cast separate, distinct votes for President and Vice President – the system we still use today.

The Election of 1824: The “Corrupt Bargain”

Just two decades later, the 12th Amendment’s solution faced its own test.

The Crisis: A four-way race fractured the Electoral College. Andrew Jackson won the most popular votes and the most electoral votes, but he failed to secure the required absolute majority. The other contenders were John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay, and William Crawford.

The Constitutional Mechanism: The 12th Amendment was again invoked, sending the decision to the House of Representatives. Under the rules, the House could only choose from the top three candidates, eliminating Henry Clay.

The Resolution & Legacy: As Speaker of the House, the eliminated Henry Clay was now the kingmaker. He despised Jackson. He threw his support behind John Quincy Adams, who won the vote in the House. Days later, President-elect Adams nominated Henry Clay to be his Secretary of State. Jackson’s supporters were enraged, screaming that a “Corrupt Bargain” had stolen the election and thwarted the will of the people. The legacy was profound: the old political party system collapsed, and a furious wave of Jacksonian democracy swept the nation, carrying a vengeful Andrew Jackson to a landslide victory four years later.

“The ‘Corrupt Bargain’ of 1824 left a deep scar on the American psyche, creating a powerful and lasting suspicion that backroom deals in Washington can override the voice of the voter.”

The Election of 1876: The Compromise that Ended Reconstruction

This was arguably the most dangerous and consequential electoral crisis in American history, second only to the Civil War itself.

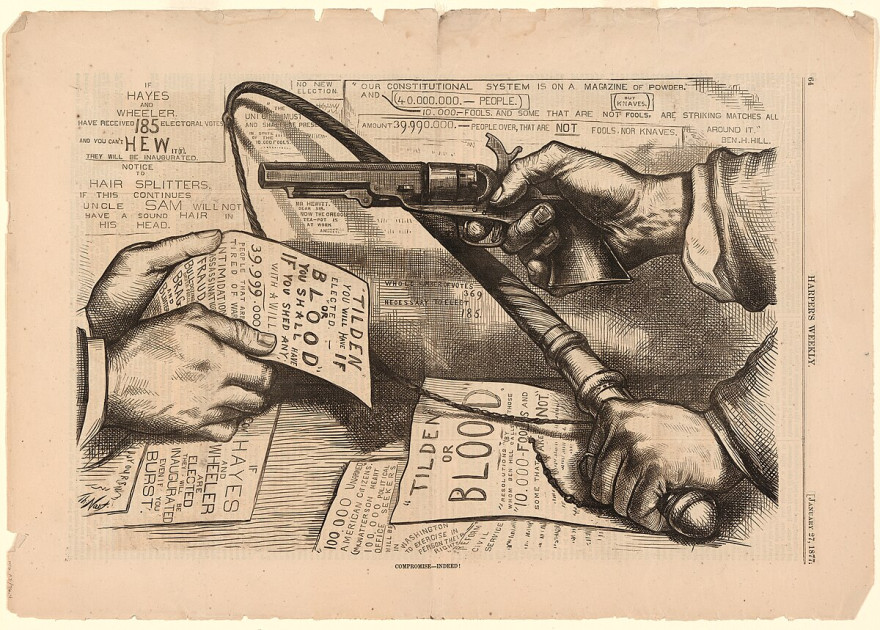

The Crisis: Democrat Samuel Tilden won the popular vote by a comfortable margin and was just one electoral vote shy of the presidency. However, the electoral votes from four states – Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Oregon – totaling 20, were disputed due to massive fraud, violence, and voter intimidation against Black Republican voters in the South.

The Constitutional Mechanism: The Constitution provided no clear path to resolve a dispute over competing slates of electors. With the nation on a knife’s edge, Congress created an ad-hoc, extra-constitutional Electoral Commission made up of five Senators, five House members, and five Supreme Court justices.

The Resolution & Legacy: The commission, which had an 8-7 Republican majority, voted along strict party lines to award every single disputed electoral vote to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, making him President by a single electoral vote. The political deal that allowed this to happen is known as the Compromise of 1877. In exchange for Democrats accepting the outcome, Republicans agreed to withdraw the last federal troops from the South. The legacy was tragic and immediate: the end of the Reconstruction era and the beginning of a century of Jim Crow oppression.

The Election of 2000: A Battle in the Courts

For a generation of Americans, this is the electoral crisis that defines all others.

The Crisis: The entire election between Republican George W. Bush and Democrat Al Gore came down to a few hundred votes in the state of Florida. The razor-thin margin triggered an automatic recount and a month-long, chaotic series of legal battles over recount procedures, ballot designs, and the infamous “hanging chads.”

The Constitutional Mechanism: For the first time in history, the U.S. Supreme Court became the final arbiter of a presidential election.

The Resolution & Legacy: In a deeply controversial 5-4 decision in Bush v. Gore, the Supreme Court halted the Florida recount, citing concerns that the lack of a uniform standard for counting votes violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The decision was a per curiam ruling, meaning it was not to be used as precedent, but its practical effect was to end the recount and hand the presidency to George W. Bush.

“The legacy of Bush v. Gore is a fierce and lasting debate over the proper role of the judiciary in resolving a political dispute, a question that continues to echo in our politics today.”

A Republic Tested

Each of these four crises pushed the American system of government to its limits. They reveal a system that is both remarkably resilient and dangerously fragile.

The Constitution provides mechanisms to resolve these disputes, but each time they have been used, they have left deep scars on the nation and fundamentally altered the course of American history. These events are a powerful reminder that the peaceful transfer of power is not automatic; it is a hard-won and deeply contested achievement.