An illegal immigrant from India was driving a commercial truck on Interstate 40 in Oklahoma carrying a New York state CDL with “NO NAME GIVEN” listed as his first name. ICE arrested Anmol Anmol during a routine truck scale inspection on September 23, discovering he entered the country illegally in 2023 after being released by the Biden administration.

The arrest was part of a three-day operation targeting illegal immigrant truck drivers that netted 120 arrests, with 91 operating commercial motor vehicles using licenses issued by sanctuary states. The enforcement action followed the high-profile Florida crash where illegal immigrant Harjinder Singh – driving with a California CDL despite failing English proficiency tests – killed three people in August.

DHS says sanctuary states are issuing commercial driver’s licenses to people who shouldn’t be operating 80,000-pound vehicles on American highways. New York officials say they followed federal guidelines and that having only one name isn’t uncommon for individuals from other countries.

Explaining How Someone Gets a License With “No Name Given”

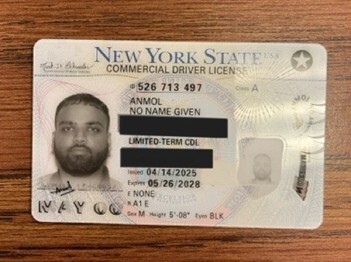

Anmol’s New York commercial driver’s license was issued in April 2025 and remains valid until May 2028. The redacted photo obtained by Fox News shows it’s a Class A CDL – the classification required for operating tractor-trailers and other large commercial vehicles. The license includes a star indicating it’s a REAL ID compliant document.

New York DMV officials told Fox News Digital that the license holder has lawful status through federal employment authorization issued in March. They said the license “was issued in accordance with all proper procedures, including verification of the individual’s identity through federally issued documentation.”

“It is not uncommon for individuals from other countries to have only one name,” the DMV official explained, adding that “procedures for that are clearly spelled out in the US Citizenship and Immigration Services policy manual” and that “federal documents also include a ‘no name given’ notation.”

DHS Assistant Secretary Tricia McLaughlin disputed that characterization: “The Biden Administration gave this illegal alien work authorization in 2023” but “work authorization does not give anyone lawful immigration status.”

That distinction matters legally. Work authorization allows someone to hold employment while their immigration case is pending, but it doesn’t confer lawful permanent resident status or citizenship. Someone with work authorization but no underlying legal status to remain in the country is still deportable once that authorization expires or gets revoked.

McLaughlin called it “insane that New York is issuing commercial drivers licenses to illegal aliens” and said the state needs “stricter standards for issuing commercial drivers licenses.”

When Fox News pressed further about Anmol’s immigration status, the New York DMV official responded: “Any questions about immigration documentation should be directed to the federal government.”

Understanding the Federal-State Conflict Over CDL Standards

The disagreement between DHS and New York DMV reflects broader tensions about sanctuary state policies and federal immigration enforcement. New York follows federal guidelines about who qualifies for driver’s licenses based on documentation applicants provide. If federal agencies issue work authorization, New York treats that as sufficient basis for licensing.

DHS argues that states should apply stricter standards than just accepting federal work authorization, particularly for commercial licenses that allow operating heavy trucks and transporting hazardous materials. They want states verifying immigration status beyond employment authorization.

Oklahoma Governor Kevin Stitt framed the issue bluntly: “If New York wants to hand out CDLs to illegal immigrants with ‘No Name Given,’ that’s on them. The moment they cross into Oklahoma, they answer to our laws.”

That statement reflects how interstate commerce complicates enforcement. Trucks licensed in one state operate nationwide, meaning New York’s licensing standards affect highway safety in Oklahoma, Florida, and every other state commercial vehicles travel through.

The 287(g) program that enabled Oklahoma Highway Patrol to work directly with ICE on these arrests allows state and local law enforcement to enforce federal immigration law. That partnership is what made the three-day operation possible, resulting in 120 arrests across multiple nationalities.

Measuring the Public Safety Concerns Behind the Enforcement

ICE Deputy Director Madison Sheahan said illegal immigrants “have no business operating 18-wheelers on America’s highways.” The statement reflects safety concerns about drivers who may lack proper training, English proficiency for reading signs and communicating with other drivers, or familiarity with American traffic laws.

Among the 120 arrested during the Oklahoma operation were individuals from India, Uzbekistan, China, Russia, Georgia, Turkey, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Mauritania. DHS said many posed public safety risks “by operating 80,000-pound commercial vehicles without proper verification.”

Beyond immigration violations, some arrestees had criminal histories including DUI convictions, money laundering, human smuggling, assault, conspiracy to distribute cocaine, controlled substance possession, and illegal re-entry. Guatemalan national Kevin Ivan Escobar-Dionicio had charges for human smuggling and money laundering. Cuban Adrian Betancourt Rodriguez had cocaine distribution convictions. Russian Firuz Khamidov faced forgery charges.

These criminal histories suggest the highway enforcement operations are identifying more than just immigration violations – they’re removing drivers with demonstrated disregard for law from operating commercial vehicles.

The enforcement comes after the August Florida crash where Harjinder Singh killed three people. Singh held a California CDL despite failing English language proficiency assessments and correctly identifying only one of four roadway signs during testing. That case raised questions about how California issued commercial licenses to someone who couldn’t read basic traffic signs.

Connecting Individual Cases to Systematic Policy Debates

The “NO NAME GIVEN” license serves as symbolic example in broader debate about sanctuary state policies. Critics argue it demonstrates absurdity of issuing commercial driver’s licenses without verifying full legal names or immigration status. Defenders argue it reflects federal guidance about accommodating naming conventions from other countries.

Both characterizations contain truth. Federal policy does account for individuals from cultures where single names are common. But issuing commercial licenses – which authorize operating vehicles that can kill multiple people if driven negligently – should involve higher verification standards than standard driver’s licenses.

The debate extends beyond just immigration enforcement to questions about state responsibility for public safety. When California issues a CDL to someone who fails English proficiency tests, and that driver kills people in Florida, which state bears responsibility? When New York issues licenses that Oklahoma determines create safety risks, who’s accountable when accidents occur?

These aren’t hypothetical questions. The Florida crash killed three people. The victims’ families want answers about how Singh obtained a license despite obvious disqualifications. Other states want assurances that sanctuary state licensing practices aren’t creating dangers on their highways.

Federal-state conflicts over immigration policy have existed throughout American history. But when those conflicts involve commercial vehicle licensing that affects interstate highway safety, the stakes extend beyond political disagreements to include very real risks of mass casualty accidents.

Forecasting Where Highway Enforcement Operations Lead

ICE has announced it’s working with the Department of Transportation and state law enforcement to identify and remove illegal immigrant truck drivers from American highways. The Oklahoma operation represents one example of that coordination, but similar operations will likely occur in other states with 287(g) partnerships.

The enforcement creates pressure on sanctuary states to tighten commercial licensing standards even if they maintain broader policies about issuing standard driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants. Public safety concerns about commercial vehicles are harder to dismiss than general immigration enforcement debates.

States like California and New York may revise their CDL verification procedures while maintaining sanctuary policies for other purposes. That would address the specific highway safety concerns while preserving broader political commitments to protecting undocumented immigrants from deportation.

Alternatively, they may resist any changes and argue that federal government should improve its own work authorization processes rather than demanding states impose additional verification beyond federal documentation. That positions the conflict as federal responsibility rather than state policy failure.

Either way, the Florida crash and subsequent enforcement operations have elevated commercial driver licensing into national political debate. The “NO NAME GIVEN” license provides a memorable example that will feature in those debates regardless of whether it actually represents systematic problems or just unusual edge case.

Anmol Anmol is now in removal proceedings. His New York CDL won’t authorize him to operate commercial vehicles after deportation. But the policy questions his case raised – about sanctuary state licensing standards, federal-state immigration conflicts, and highway safety regulations – will persist long after his individual case concludes.

DHS says sanctuary states are putting American drivers at risk by issuing commercial licenses without adequate verification. Sanctuary states say they’re following federal guidelines and that DHS should improve its own authorization processes. The debate will continue as more enforcement operations identify additional illegal immigrant commercial drivers operating on American highways with licenses issued by states applying different verification standards.