A president threatens to federalize a city’s police force. States legalize marijuana while federal law forbids it. Governors sue the administration over an environmental rule. Every day, the headlines are filled with stories that reveal a fundamental, deliberate, and often-fierce conflict at the heart of our government.

This is the perpetual tug-of-war between the states and the federal government in Washington, D.C. To understand these battles, and what they mean for you, you must first understand one of the most powerful and misunderstood concepts in the Constitution: federalism.

Division of Powers

The framers of the Constitution were deeply suspicious of concentrated power. Their solution was to create a system with two levels of government, each with its own defined responsibilities.

What are Federal Powers? Under Article I, Section 8, the federal government is given a list of specific, enumerated powers. These are things that affect the entire nation, such as the power to declare war, coin money, establish post offices, and regulate commerce between the states.

What are State Powers? The Tenth Amendment is the bedrock of state power. It says that any power not specifically given to the federal government is reserved to the states.

This gives states the authority to regulate the daily lives of their citizens – often called the “police power” – which includes running local schools, issuing driver’s licenses, setting traffic laws, and prosecuting most crimes.

The States’ Power: The 10th Amendment

The foundation of state power is the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution. It is a simple but powerful declaration that all powers not specifically delegated to the federal government, nor prohibited to the states, are “reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

This is the source of what is often called the states’ “police power” – the inherent authority to regulate the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of their citizens.

This is why states, not the federal government, have the primary authority over most criminal law, education, and public health.

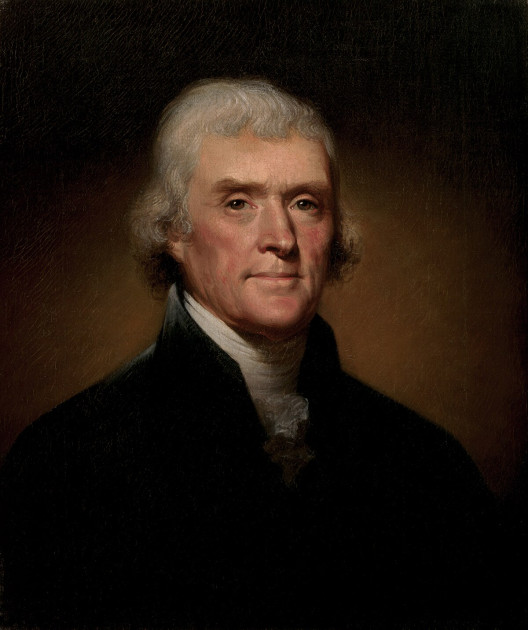

“I consider the foundation of the Constitution as laid on this ground that ‘all powers not delegated to the United States, by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states or to the people.’ To take a single step beyond the boundaries thus specially drawn around the powers of Congress, is to take possession of a boundless field of power, not longer susceptible of any definition.”

The Federal Power: The Supremacy and Commerce Clauses

The counterweight to the 10th Amendment is the power of the federal government. Article VI of the Constitution, the Supremacy Clause, states that the Constitution and the federal laws made in pursuance of it are the “supreme Law of the Land.”

The most significant source of federal power has been the Commerce Clause in Article I, which gives Congress the authority “To regulate Commerce… among the several States.”

Originally intended to prevent trade wars between the states, this clause has been interpreted over time – most famously in the 1942 case Wickard v. Filburn – to give the federal government vast authority to regulate almost any economic activity.

History’s Most Controversial Fringe Cases

This division of power seems clear on paper, but in reality, the line between state and federal authority has been the subject of some of the most intense and surprising legal battles in American history.

The Case of the Farmer’s Wheat: The most famous “fringe case” is Wickard v. Filburn (1942). The Supreme Court ruled that the federal government could fine a farmer for growing more wheat than was allowed on his own farm for his own personal use.

The Court’s logic was that by growing his own wheat, he wasn’t buying it, and if enough farmers did that, it would affect the national price of wheat. This single case represents the high-water mark of federal power under the Commerce Clause.

The Case of the Gun in School: For decades, it seemed there was no limit to federal power. Then came United States v. Lopez (1995). The Supreme Court struck down a federal law that banned guns in local school zones, ruling that carrying a gun was not an “economic activity” that Congress could regulate under the Commerce Clause.

It was the first time in nearly 60 years that the Court had placed a limit on this federal power.

The Case of the Right to Die: In Gonzales v. Oregon (2006), the state of Oregon had legalized physician-assisted suicide. The U.S. Attorney General tried to use the federal Controlled Substances Act to prosecute the doctors involved.

The Supreme Court sided with Oregon, ruling that the federal government could not use a national drug law to interfere with a state’s traditional power to regulate the practice of medicine.

The Referee: The Role of the Supreme Court

When the federal government’s power under the Commerce Clause collides with a state’s power under the 10th Amendment, the Supreme Court acts as the ultimate referee.

The balance of power in our republic has shifted back and forth throughout our history, depending on how the Court has interpreted these core constitutional provisions.

Federalism is not a settled historical doctrine. It is a dynamic, ongoing negotiation over power and sovereignty. This constant tension is not a flaw in our system; it is the system working exactly as the framers intended, as a crucial and permanent check on the concentration of power in any single level of government.