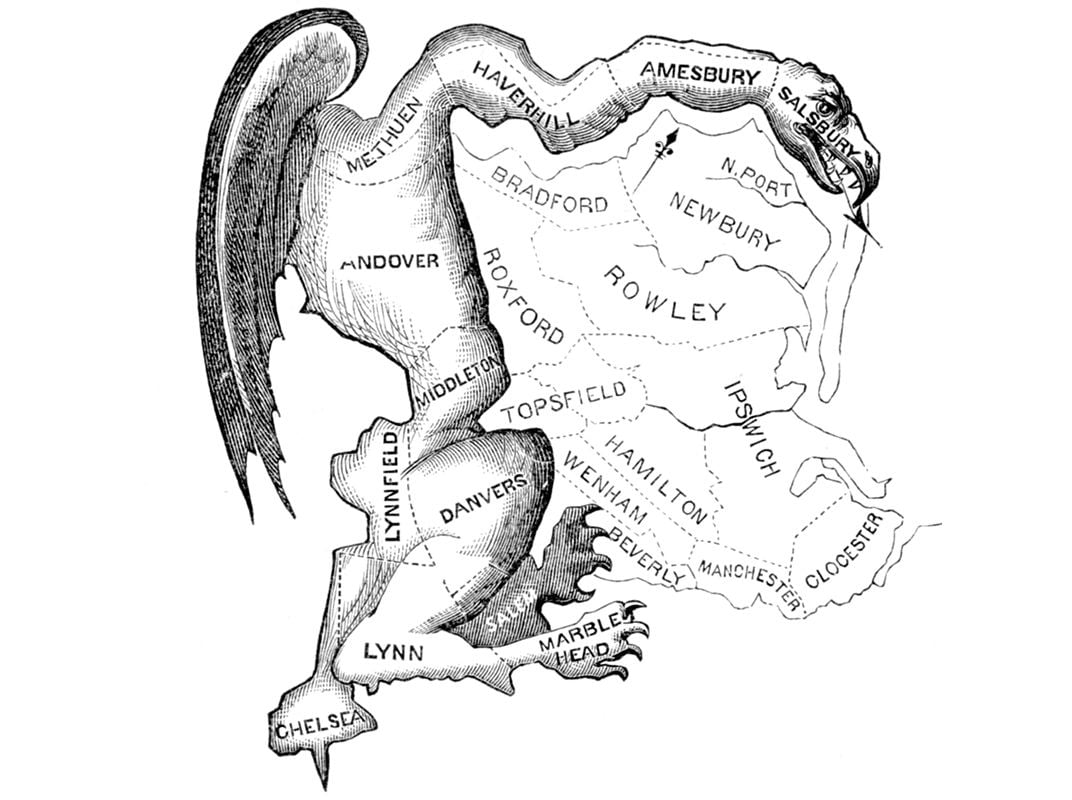

In 1812, Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry signed off on a new state senate district so bizarrely shaped that his opponents famously said it looked like a mythical salamander. A local newspaper cartoonist combined the two, and the “Gerry-mander” was born.

For over 200 years, this dark art of political map-making – the practice of drawing electoral districts to give one party an unfair advantage – has been a persistent and controversial feature of American democracy.

Understanding how it works, and why the Supreme Court has recently allowed it to flourish, is essential to understanding the brutal political battles, like the one currently raging in Texas, that define our era.

At a Glance: Gerrymandering Explained

- What it is: The practice of drawing electoral district lines to benefit one political party over another.

- How it works: The two main techniques are “cracking” (splitting a rival party’s voters into multiple districts to dilute their power) and “packing” (concentrating a rival party’s voters into a single district to waste their votes).

- The Law: Racial gerrymandering is illegal under the Voting Rights Act of 1965. However, the Supreme Court ruled in 2019 that partisan gerrymandering is a “political question” that federal courts cannot resolve.

- The Illinois Example: Both parties in Illinois have used gerrymandering when in power, but the current Democratic-drawn map is considered one of the most effective partisan gerrymanders in the nation.

The Dark Art of ‘Cracking’ and ‘Packing’

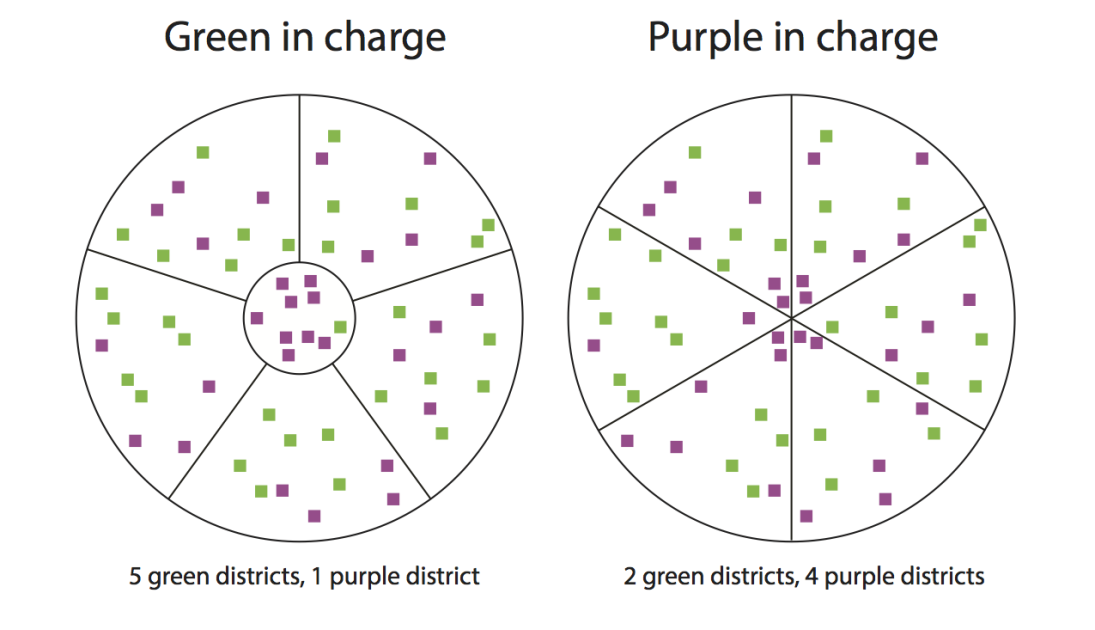

The goal of a partisan gerrymander is simple: to win the most seats, not necessarily the most overall votes. Map-drawers achieve this through two primary techniques.

“Cracking” involves taking a large, concentrated bloc of the opposing party’s voters and splitting them up into several surrounding districts. This dilutes their voting power, ensuring they are the minority in each new district and cannot elect their preferred candidate.

“Packing” is the opposite. It involves drawing a district to include as many of the opposing party’s voters as possible. This concedes one “sacrificial” district to the opposition with an overwhelming majority, but makes all the surrounding districts safer for the party in power by removing hostile voters.

Illinois: A Case Study in Bipartisan Abuse

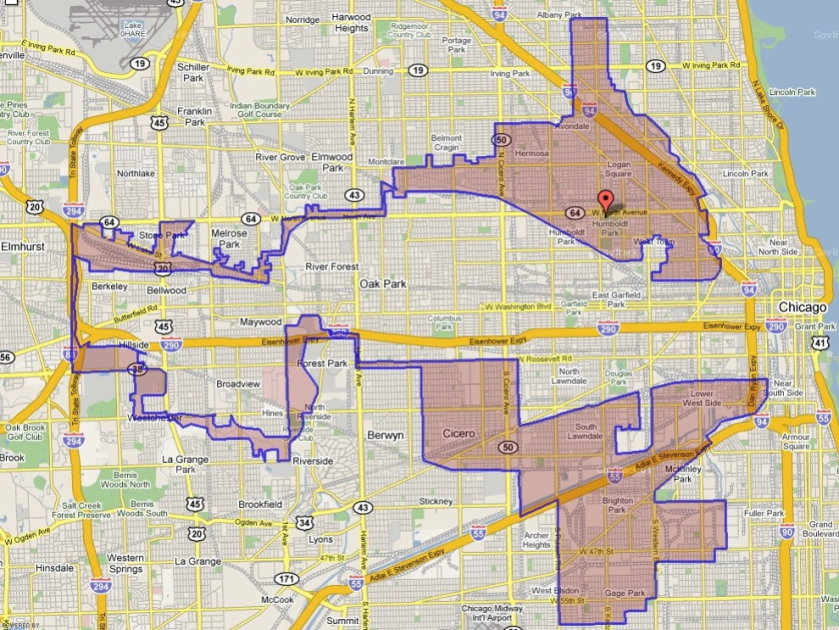

While Republicans in Texas are currently under fire for their proposed map, the state the fleeing Democrats chose as their refuge – Illinois – is a textbook example of how gerrymandering is a weapon used by both parties.

Illinois has a long history of both parties abusing the process when they control the state legislature. But the congressional map drawn by Democrats after the 2020 Census is a modern masterpiece of the craft. It successfully transformed the state’s congressional delegation from 13 Democrats and 5 Republicans to 14 Democrats and just 3 Republicans.

“Call this new Illinois map the ‘Nancy Pelosi Protection Plan.’” – Illinois GOP Chairman Don Tracy

Perhaps the most famous district in the country is Illinois’s 4th, nicknamed “the earmuffs.” It is a bizarrely shaped district designed to connect two large, geographically separate Hispanic communities in Chicago. This is a perfect example of the complexity of the issue: while it looks like a gerrymander, it was drawn to comply with the Voting Rights Act by creating a legal “majority-minority” district, ensuring the city’s large Hispanic population could elect a representative of its choice.

What Makes a Gerrymander Illegal?

The legal landscape surrounding gerrymandering is defined by a critical distinction made by the Supreme Court.

Racial Gerrymandering: Drawing maps to intentionally dilute the voting power of racial minorities is illegal. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 explicitly forbids this, and courts will strike down maps that are found to be racially discriminatory.

Partisan Gerrymandering: Drawing maps for purely political advantage, however, is another story. In the landmark 2019 case Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court’s conservative majority ruled that partisan gerrymandering is a “political question” that is “non-justiciable,” meaning it is beyond the authority of federal courts to decide.

The Supreme Court has drawn a sharp, if controversial, line: Courts can strike down a map for discriminating based on race, but not for discriminating based on party. This is the decision that has unleashed the current political wars.

The Search for a Fairer Map

With the Supreme Court largely on the sidelines, the fight over partisan gerrymandering has moved into the realm of raw political power. The Texas walkout is a prime example of the extreme tactics now being used.

Reformers have proposed several solutions. Some states, like California and Arizona, have given map-drawing power to independent, non-partisan commissions with mixed results. Others have proposed a more radical solution: dramatically expanding the size of the U.S. House of Representatives from its current 435 members. This, they argue, would create smaller districts and make any single gerrymander less impactful on the national balance of power.

For now, this 200-year-old problem remains one of the most significant challenges to the health of American democracy, a system where, all too often, the voters are not the ones choosing their representatives.