The American Presidency is the most powerful office on Earth. A single individual can command armies, negotiate with world leaders, and shape the course of history. But in our modern, often-heated political discourse, the immense power of the office can lead to a fundamental misunderstanding of its nature.

The President is not a king. The framers of the Constitution, deeply suspicious of concentrated authority, deliberately designed a system of checks and balances to limit executive power.

Taking a step back from the daily headlines to understand the powers the president doesn’t have is one of the most important civic duties for any American.

1. The President Does Not Control the Economy

In modern politics, it has become standard practice for presidents to take full credit for a good economy and receive full blame for a bad one. This is a political reality, but it is not a constitutional one. The Constitution deliberately gives the primary economic powers to Congress.

Under Article I, it is Congress that has the power to tax, to borrow money, to coin money, and, most importantly, to regulate interstate and foreign commerce.

The President’s role is influential but secondary; he can propose budgets and sign or veto tax bills, but he does not hold the nation’s purse strings. Furthermore, a key lever of economic power – monetary policy – is controlled by the independent Federal Reserve, an institution deliberately designed to be insulated from a president’s political influence.

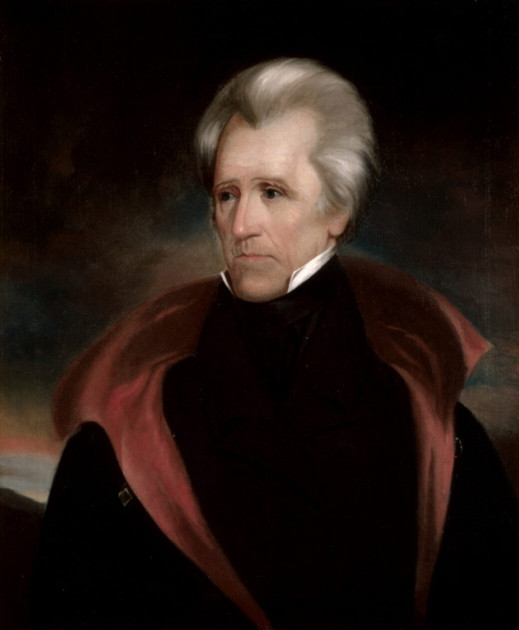

This tension is as old as the republic itself. We saw it when Andrew Jackson waged his famous war against the Second Bank of the United States, using his veto power to challenge the nation’s financial elite.

We saw it when Franklin D. Roosevelt, frustrated by a Supreme Court that repeatedly struck down his New Deal programs, threatened to pack the court with new justices.

In both cases, the presidents were immensely powerful, but they could not unilaterally dictate the nation’s economic fate without a battle with the other branches.

2. The President Cannot Spend Money at Will

This leads to a second, critical misunderstanding. The President cannot simply direct federal funds toward his priorities by decree. The Constitution is unambiguous: Congress has the exclusive “Power of the Purse.”

Not a single dollar can be spent from the U.S. Treasury without an appropriation law passed by the legislative branch.

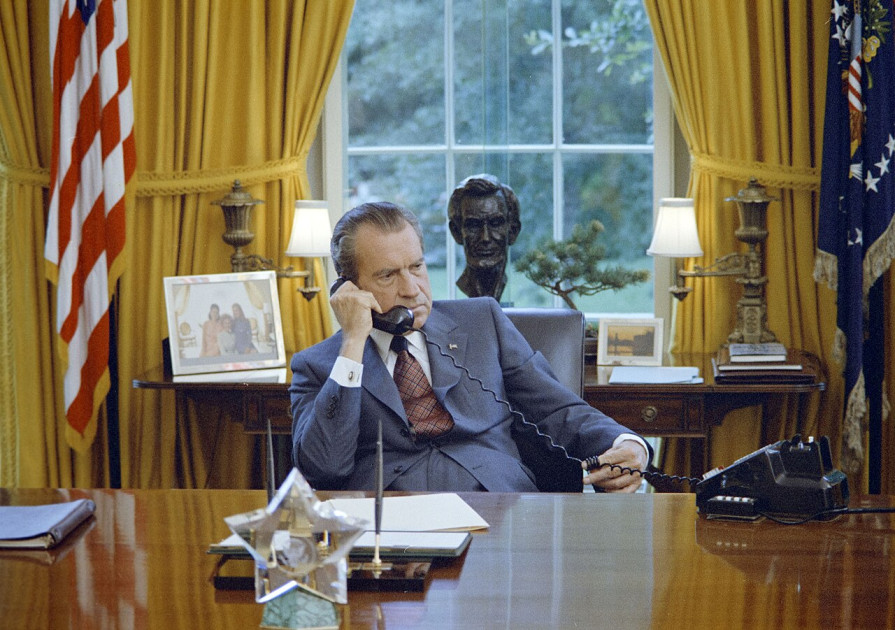

This principle was famously tested during a constitutional crisis with President Richard Nixon, who refused to spend money Congress had appropriated for programs he opposed – a practice known as impoundment.

In response, Congress passed the Impoundment Control Act of 1974, making it illegal for a president to unilaterally withhold funds that have been lawfully appropriated.

An even more dramatic and illegal example occurred during the Iran-Contra affair, where officials in the Reagan administration secretly and unconstitutionally circumvented Congress’s explicit prohibition on funding, demonstrating the grave crisis that occurs when the executive defies the power of the purse.

3. An Executive Order is Not a Law

Perhaps the most common misunderstanding of presidential power is the nature of the Executive Order. In an era of congressional gridlock, presidents of both parties have increasingly turned to EOs to enact their agendas, giving the impression that they can make law with the stroke of a pen.

This is not the case. An Executive Order is not a new law. It is a directive from the President to the executive branch on how to implement or enforce existing laws passed by Congress.

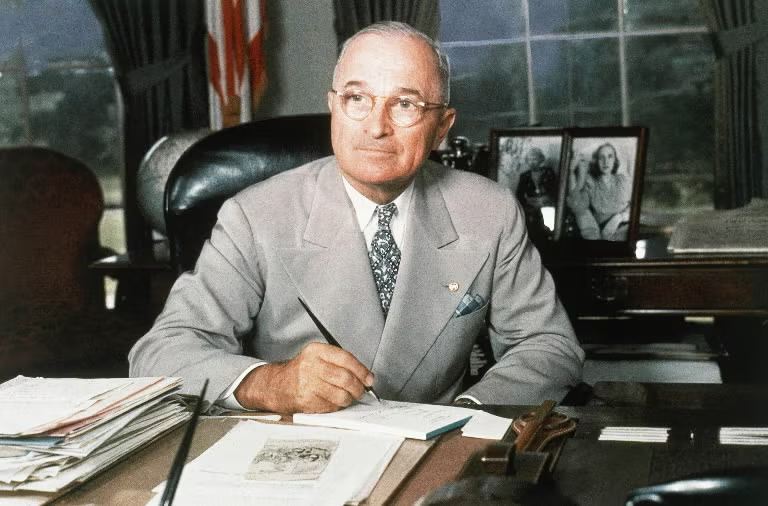

A president can use an EO to direct the military (as Truman did to desegregate the armed forces) because he is its Commander-in-Chief.

He cannot, however, use an EO to create a new program, appropriate new funds, or override a statute passed by Congress.

The ultimate check on this power was established by the Supreme Court in the landmark 1952 case Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer. The Court struck down President Truman’s executive order to seize steel mills during the Korean War, ruling that he had exceeded his constitutional authority and was attempting to make law, a power that belongs to Congress alone.

In our hyper-focused media environment, it is easy to view the President as an all-powerful figure. A sober reading of the Constitution, however, reveals a different picture: an office of immense authority, but one that is deliberately and brilliantly constrained by a system of checks and balances. Understanding the powers the President doesn’t have is just as vital to a healthy republic as understanding the ones he does.