The Justice Department released hundreds of thousands of pages of Jeffrey Epstein files Friday afternoon, meeting a 30-day deadline imposed by a law President Trump signed in November after fellow Republicans pressured him to stop blocking their release.

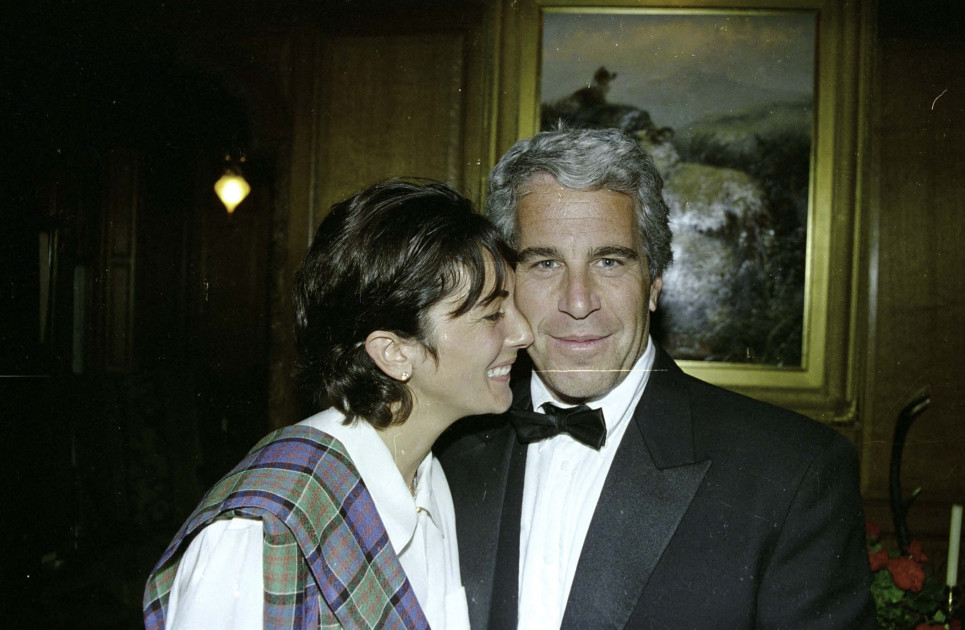

The files include new photos of Epstein with former President Bill Clinton. They identify more than 1,200 victims and their families. They contain names of “politically exposed people and government officials” whose identifiers have been redacted using the same standards applied to victims.

And they expose the constitutional tension at the heart of government transparency: when Congress forces the executive branch to release information the President tried to keep secret, who actually controls what the public learns about government operations?

Trump spent years fighting to keep these files sealed. Then his own party passed a law requiring their release. Now his Justice Department is complying while simultaneously opening investigations that could allow them to withhold additional documents under exceptions the law provides.

The result is transparency achieved through legislative compulsion, not executive cooperation – and it raises questions about whether Congress can actually force accountability when the executive branch controls both the files and the process for reviewing them.

Discussion

Oh please, spare me the drama. Dems having a meltdown? The only meltdown here is over exaggerations. It's just another politicized circus act, nothing to get excited about.

Finally, accountability! Time to shine some light on those dark secrets.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

What Congress Demanded and What Trump Delivered

The Epstein Files Transparency Act required the Justice Department to release within 30 days “all unclassified material in its possession” related to Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell’s sex trafficking cases. That includes FBI reports, witness interviews, flight logs, communications with government officials, immunity deals, and documentation of Epstein’s detention and death.

The law allows redactions to protect victims, ongoing investigations, or information that could jeopardize national defense or foreign policy. But it explicitly states that “no records shall be withheld or redacted due to embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity.”

That last provision is aimed directly at the political discomfort these files create. Epstein had connections to powerful people across the political spectrum. His crimes implicated wealthy financiers, politicians, academics, and celebrities. The files document who knew what, when they knew it, and what they did about it.

Trump signed the bill under pressure from Republicans in Congress, but Deputy Attorney General Todd Blanche’s letter makes clear the administration views this as a voluntary act of transparency rather than compelled disclosure. “Never in American history has a President or the Department of Justice been this transparent with the American people about such a sensitive law enforcement matter,” Blanche wrote.

That framing is politically strategic. By claiming credit for transparency while actually complying with a statutory mandate, the administration positions itself as cooperating rather than being forced to disclose information it tried to keep hidden.

The Redaction Standards Nobody Can Verify

The Justice Department assigned over 200 attorneys to review the files and determine what could be released. They identified 1,200 victims whose names and identifying information have been redacted. They also redacted names and identifiers of “politically exposed individuals and government officials” using the same standards applied to victims.

Here’s the problem: Congress has no way to verify that those redaction standards were actually applied consistently. The law allows victim protection redactions, but it also says politically sensitive information can’t be withheld. Whether a specific redaction protects a victim or shields a powerful person from embarrassment depends on judgments made by DOJ attorneys working under an administration led by someone mentioned in the files.

Blanche’s letter states that the review “did not reveal credible evidence that Epstein blackmailed prominent individuals, nor did it uncover evidence that could predicate an investigation against uncharged third parties.”

That conclusion is significant – it means the DOJ isn’t pursuing charges against people whose names appear in the files.

But how can Congress or the public verify that conclusion when the underlying evidence has been redacted? The files might contain information suggesting criminal conduct by powerful individuals that DOJ chose not to investigate. Or they might genuinely show no prosecutable offenses beyond what Epstein and Maxwell were already charged with. There’s no way to distinguish between those possibilities without seeing what’s been withheld.

This is the fundamental problem with executive control over transparency: the institution deciding what to release is the same institution whose activities the documents describe.

The Active Investigation Exception That Never Ends

Attorney General Pam Bondi recently opened a new investigation in New York into Epstein’s ties to Democrats. That investigation creates an exception under the transparency law allowing DOJ to withhold files that “could jeopardize pending investigations or litigation.”

The timing is notable. The law requires release of all files except those that would harm ongoing investigations. Opening a new investigation just before the release deadline creates a basis to withhold additional documents while claiming compliance with the transparency mandate.

This isn’t necessarily improper – if there’s a legitimate investigative basis for examining Epstein’s connections, DOJ should pursue it. But it illustrates how executive branch control over investigations allows administrations to regulate their own transparency obligations.

Congress can require document releases. But if the executive branch can always open new investigations that justify withholding documents, then the transparency requirement becomes negotiable. The files get released eventually, but “eventually” can stretch for years while investigations remain “pending.”

What Article II Actually Says About Executive Privilege

The Constitution doesn’t explicitly address document disclosure or executive privilege. Article II vests “the executive Power” in the President and requires that he “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” Courts have interpreted that to include a limited privilege to withhold certain communications from Congress and the public.

But executive privilege isn’t absolute. When Congress passes a law requiring disclosure, the executive branch must comply unless withholding is necessary to protect core executive functions or privileges specifically recognized by courts. Criminal investigative files don’t generally qualify for absolute protection – they’re subject to disclosure through FOIA, subpoenas, and statutes like the Epstein transparency law.

Trump’s initial resistance to releasing the files suggested he believed executive privilege protected them from disclosure. Congress’s passage of the transparency law asserted that no such privilege applies when statute requires release. Trump’s signature conceded the point – though the administration’s framing suggests they view this as voluntary cooperation rather than compelled compliance.

The constitutional question isn’t whether Trump had to sign the bill – he could have vetoed it, forcing Congress to override. The question is whether the executive branch can functionally limit congressional oversight by controlling the review process, making redaction decisions without verification, and opening investigations that justify withholding additional documents.

The Separation of Powers Problem

Congress has Article I authority to legislate, investigate executive branch conduct, and demand information necessary for oversight. The executive branch has Article II authority to control law enforcement operations and protect sensitive information related to ongoing investigations and national security.

When those authorities conflict, the Constitution doesn’t provide a clear hierarchy. Congress can pass transparency laws. The executive branch can cite legitimate exceptions. Courts can resolve specific disputes, but they can’t force the executive branch to release documents it’s already destroyed, lost, or classified under national security authorities.

The Epstein files release illustrates this problem in practice. Congress demanded disclosure. The administration complied, but controlled every aspect of the compliance process – which documents to review, how to review them, what standards to apply, which exceptions to invoke, and whether to open new investigations that justify additional withholding.

The result is transparency that’s technically statutory but functionally discretionary. The executive branch released what it determined the law required after applying standards it created through processes it controlled. Congress and the public get access to information, but no ability to verify whether all responsive documents were actually reviewed or whether redactions were properly applied.

Why Victims Matter More Than Transparency

The law’s victim protection provisions are constitutionally sound and morally essential. The 1,200 victims and family members identified through the DOJ review deserve privacy. Their names, identifying information, and materials depicting abuse should never be made public.

But victim protection creates cover for politically sensitive redactions that have nothing to do with protecting victims. When DOJ says it applied the same redaction standards to “politically exposed individuals and government officials” as it did to victims, that raises questions about whether all those redactions are actually victim-protective or whether some shield powerful people from accountability.

The law explicitly prohibits withholding information “due to embarrassment, reputational harm, or political sensitivity.”

But if the executive branch controls which information falls into that category versus which information must be withheld to protect victims or investigations, then the prohibition becomes unenforceable without independent verification.

This isn’t an argument for releasing victim information – it’s an argument that victim protection shouldn’t become a catch-all justification for shielding powerful people from accountability. The constitutional balance requires transparency about government conduct while protecting individual privacy. Getting that balance right requires oversight mechanisms that don’t depend solely on the executive branch policing itself.

What the Files Actually Reveal

The released documents include FBI reports, witness interviews, flight logs, and photos showing Epstein with various public figures. According to sources, new photos of Bill Clinton with Epstein are part of the release.

The sheer volume is substantial – hundreds of thousands of pages that took over 200 DOJ attorneys weeks to review. The files document a sex trafficking operation that involved powerful people, generated numerous investigations, and resulted in Epstein’s federal custody where he died under circumstances that remain disputed.

What they don’t reveal – according to DOJ’s review – is credible evidence of blackmail or prosecutable conduct by uncharged third parties. That conclusion matters enormously because it determines whether anyone beyond Epstein and Maxwell faces criminal liability for involvement in or knowledge of the trafficking operation.

If DOJ’s conclusion is accurate, the files document a horrific criminal operation by two people who are either convicted or dead, involving victims who deserve protection, but not implicating additional defendants in prosecutable crimes.

If DOJ’s conclusion is incomplete or influenced by political considerations, the files might contain evidence of criminal conduct that won’t be pursued because the people involved are too powerful or politically connected to charge.

The public can’t distinguish between those possibilities without independent verification of DOJ’s review process and conclusions – verification the constitutional structure doesn’t provide when the executive branch controls both the investigation and the disclosure.

The Ongoing Review That Delays Complete Transparency

Blanche’s letter indicates the initial release isn’t complete. The DOJ is continuing to review additional documents, expects that review to be completed “over the next several weeks,” and will inform Congress when production is complete “by the end of this year.”

That timeline extends well beyond the 30-day statutory deadline. The law required release within 30 days, not initiation of a review process that concludes months later. The administration is treating the deadline as requiring initial production with ongoing supplements, rather than complete disclosure by the deadline date.

Whether that interpretation complies with congressional intent depends on whether the statute’s language – “release…all unclassified material” – allows phased production or requires complete disclosure by the deadline. Congress could clarify through oversight or amended legislation. But absent that, DOJ’s interpretation controls the release schedule.

This is another example of executive control over transparency obligations. Congress can set deadlines, but if the executive branch determines that compliance requires extended review periods, the deadlines become aspirational rather than binding. The files get released, but the pace of release depends on executive branch resource allocation and prioritization decisions that Congress can’t directly control.

The DOJ said Friday’s release included FBI files from multiple Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell cases, grand-jury materials, and records from the Epstein death investigation, with over 200 attorneys reviewing what can be made public.

Rep. Ro Khanna warned that failure to comply with the release law could lead Congress to pursue impeachment hearings of the attorney general Pa, Bondi and deputy attorney general Todd Blanche.

What Happens When Future Administrations Face Similar Demands

The Epstein files release creates precedent about congressional power to compel disclosure of executive branch documents. If this transparency law survives legal challenge and produces meaningful disclosure despite executive resistance, Congress has a template for demanding documents in future cases involving government misconduct or politically sensitive investigations.

But if the release demonstrates that executive control over the review process allows administrations to effectively regulate their own transparency obligations, then future transparency laws become symbolic. Congress can pass requirements. The executive branch can comply in ways that satisfy the letter while avoiding the spirit of the law.

The constitutional question is whether separation of powers requires accepting that outcome. Congress has legislative and oversight authority. The executive has control over law enforcement operations and document custody. When those authorities conflict, the Constitution provides mechanisms for resolution – legislation, judicial review, funding restrictions, impeachment.

But those mechanisms only work if Congress has information sufficient to know when executive compliance is genuine versus performative. Without independent verification of what documents exist, how they were reviewed, and whether redactions were properly applied, congressional oversight becomes dependent on trusting the executive branch to police itself.

That’s not how the Framers designed the system to work.

The Transparency That Might Not Mean Much

The Justice Department released hundreds of thousands of pages of Epstein files. That’s an enormous volume of information about a politically sensitive subject involving powerful people across partisan lines.

But volume doesn’t equal transparency. Redacted documents reveal some information while concealing other information. The released files might answer important questions about who knew what and when. Or they might raise more questions while concealing the answers behind victim protection redactions, national security classifications, or ongoing investigation exceptions.

The public won’t know which until someone with authority to review unredacted files verifies DOJ’s conclusions. That verification requires either congressional access to unredacted materials – which creates its own security and privacy concerns – or judicial review of redaction decisions, which only happens if someone with standing challenges specific withholdings.

In practice, neither mechanism provides comprehensive oversight. Congress might get access to some unredacted files through classified briefings, but those briefings come with restrictions on what members can disclose publicly. Courts can review specific redaction decisions if challenged, but they can’t review documents that were never disclosed in the first place.

The Epstein files release demonstrates that congressional transparency mandates can force disclosure the executive branch wanted to prevent. But it also demonstrates that executive control over the disclosure process limits how much transparency those mandates actually achieve.

The Constitutional Question Nobody’s Asking

The real constitutional question isn’t whether Trump had to release the files – the transparency law required it, and he complied. The question is whether releasing files the executive branch reviewed, redacted, and supplemented through investigations it controls actually constitutes the transparency Congress intended.

If the answer is yes, then transparency laws work as designed – Congress can compel disclosure, and executive control over the process reflects legitimate constitutional authority to protect sensitive information. If the answer is no, then transparency laws become performative – they force releases that satisfy statutory language while allowing the executive branch to regulate what the public actually learns.

The Framers designed a system of separated powers where different branches check each other. But they didn’t anticipate a world where information exists in digital formats requiring extensive review, where national security and victim protection create legitimate exceptions to transparency, and where the institution holding the documents controls both their custody and the process for determining what can be released.

The Epstein files release tests whether Congress can effectively oversee executive branch conduct when the executive controls access to information necessary for that oversight. The answer affects not just this case, but every future dispute about government transparency and congressional authority to demand documents from executive agencies.

Trump signed the transparency law. The Justice Department released files. Whether that process actually achieved transparency or just created the appearance of it while maintaining executive control over politically sensitive information is the question that will define how much congressional oversight authority actually means in practice.

The files are public now. What they reveal – and what remains redacted – will show whether transparency laws can force accountability or just force the appearance of compliance while the executive branch retains control over what the public learns.

About time the truth's coming out! Dems gonna have a meltdown over this!