You have a constitutional right to privacy. Everyone knows that.

Except the Constitution never mentions privacy. Not once. Not in any amendment, clause, or footnote scribbled in the margins by a Founder having second thoughts.

The right exists because nine Supreme Court justices in 1965 decided it was implied by the “penumbras” – the shadows cast by other rights that are written down. They found it hiding between the lines of the First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Ninth Amendments, like a constitutional Easter egg.

This isn’t a fringe legal theory or a controversial interpretation. It’s how American constitutional law actually works. Dozens of rights you assume are explicitly guaranteed in the Constitution exist only because courts inferred them from broader language about due process, equal protection, or liberty itself.

Which means they can be un-inferred just as easily.

Discussion

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment

The Privacy Right That Started It All

In 1965, Connecticut was still enforcing a law banning married couples from using contraception. Not selling it. Not advertising it. Using it. Planned Parenthood challenged the law, and the case landed at the Supreme Court.

The Constitution doesn’t say “citizens have a right to privacy in their bedrooms.” But in Griswold v. Connecticut, the Court ruled that various amendments create “zones of privacy” that the government can’t invade. The First Amendment protects private associations. The Third bars soldiers from being quartered in homes. The Fourth protects against unreasonable searches.

Together, the Court reasoned, these amendments imply a broader right to privacy that includes marital intimacy.

That penumbral reasoning became the foundation for Roe v. Wade in 1973, which extended privacy rights to abortion decisions. It also justified protections for intimate relationships, contraception access, and other personal autonomy claims.

Then Dobbs v. Jackson arrived in 2022 and erased Roe entirely. The Court’s reasoning? The Constitution doesn’t explicitly protect abortion, and rights not “deeply rooted in history and tradition” aren’t covered by substantive due process. Privacy still exists as a concept, but its boundaries just became much more negotiable.

Marriage Isn’t in There Either

The word “marriage” appears exactly zero times in the Constitution. Yet the Supreme Court has called it “one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness” and a “fundamental right” protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Loving v. Virginia in 1967 struck down state bans on interracial marriage, holding that the right to marry is protected by both due process and equal protection clauses. The Constitution doesn’t spell out a marriage right, but the Court found it in the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee that states can’t deprive people of liberty without due process or deny them equal protection.

Forty-eight years later, Obergefell v. Hodges extended that same fundamental right to same-sex couples using identical reasoning. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion leaned heavily on the due process and equal protection clauses – the same textual anchors from Loving.

But here’s the vulnerability: both rulings rest on substantive due process, the same doctrine that Dobbs just narrowed significantly. Justice Thomas wrote in his Dobbs concurrence that the Court should “reconsider” cases like Griswold, Lawrence (sexual intimacy), and Obergefell because they all rely on substantive due process analysis he considers constitutionally unfounded.

The right to marry isn’t going anywhere quickly. But it lives in the same doctrinal neighborhood as the privacy right that just lost Roe.

Education: Wichtig, But Not a Right

Most Americans assume public education is a constitutional guarantee. It’s compulsory in every state. It’s funded by taxpayers. It’s described as the “great equalizer” and the foundation of citizenship.

The Supreme Court disagrees.

In San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973), the Court explicitly held that education isn’t a fundamental right under the federal Constitution. Texas was funding schools through local property taxes, creating massive disparities between wealthy and poor districts. Families in poor districts sued, arguing that unequal funding violated equal protection.

The Court said no. Education matters, but it’s not in the Constitution’s text or “implicitly guaranteed” by other provisions. States can structure their school systems however they want, as long as they don’t discriminate based on suspect classifications like race.

Plyler v. Doe (1982) carved out a narrow exception when Texas tried to deny K-12 education to undocumented children. The Court struck that down under equal protection – you can’t create an underclass of children who’ve committed no crime themselves. But the ruling carefully avoided declaring a general federal right to education.

The result? Educational access and quality vary wildly by zip code, and there’s no constitutional floor beneath which states can’t fall. If a state wanted to shut down its public schools entirely, the federal Constitution wouldn’t stop it.

Healthcare Lives in the Same Constitutional Void

There’s no right to healthcare in the Constitution. Not preventive care. Not emergency treatment. Not prescription drugs or mental health services.

Courts have recognized narrow medical autonomy rights under substantive due process – you can refuse treatment, even life-saving treatment. But that’s a right to say no, not a right to access care.

The entire Affordable Care Act debate hinged on Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce and levy taxes, not on whether Americans have a constitutional right to health insurance. When the Supreme Court upheld the individual mandate in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), it did so by calling the penalty a permissible tax. The Court explicitly rejected the argument that Congress could compel people to buy insurance under the Commerce Clause.

Healthcare litigation focuses on what government can do under its enumerated powers, not what it must do to protect a fundamental right. Congress can create Medicare, Medicaid, and the VA system through its spending power. It could also repeal all of them tomorrow, and the Constitution wouldn’t blink.

Whether healthcare should be a right is a policy question. Whether it is a right under current constitutional law isn’t even close.

Voting: More Complicated Than You Think

Ask anyone if voting is a constitutional right, and they’ll say yes immediately. And they’re mostly correct – but not in the way they assume.

There’s no single “right to vote” clause in the Constitution. Instead, there’s a patchwork of amendments that prohibit specific forms of discrimination: The Fifteenth Amendment bars race-based restrictions. The Nineteenth bars sex-based restrictions. The Twenty-Sixth bars age-based restrictions for citizens 18 and older.

But the Constitution doesn’t affirmatively grant voting rights. It constrains how states can restrict them.

States still control voter qualifications, registration systems, polling locations, and election administration. They can require ID. They can purge voter rolls. They can restrict early voting and mail ballots. As long as they don’t discriminate based on race, sex, or age, most restrictions survive constitutional scrutiny.

The Supreme Court has called voting “fundamental” and applied strict scrutiny to some restrictions. But that protection comes from equal protection analysis and substantive due process, not from explicit constitutional text creating a right to vote.

Why the Gaps Matter Now

These aren’t academic distinctions. They’re fault lines that determine which rights can withstand political pressure and which ones collapse when the Court’s composition shifts.

Rights written explicitly in the text – speech, religion, due process, equal protection – are harder to eliminate. They’d require constitutional amendments, which need two-thirds of Congress and three-fourths of states to ratify.

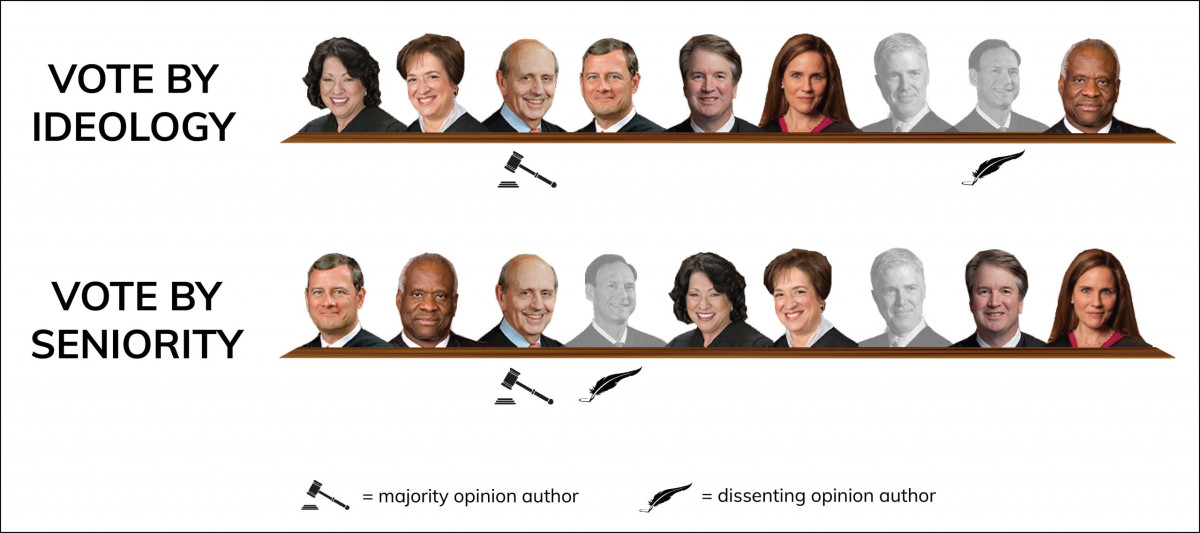

Rights inferred from broader clauses? Those can disappear with five votes on the Supreme Court.

Dobbs proved it. Fifty years of precedent protecting abortion rights vanished because a new Court majority decided the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause doesn’t cover reproductive decisions after all.

The same doctrinal tools that erased Roe are sitting right next to Griswold, Loving, and Obergefell in the constitutional toolbox. Justice Thomas said the quiet part loud in his Dobbs concurrence: substantive due process cases should be reconsidered across the board.

Whether that happens depends entirely on future Court appointments and which cases reach the justices. But the vulnerability is structural. Rights that exist between the lines can be erased by reinterpreting what the lines mean.

The Constitution protects what it says and what courts say it implies. When courts change their minds about what’s implied, the rights that millions of people rely on can evaporate overnight.