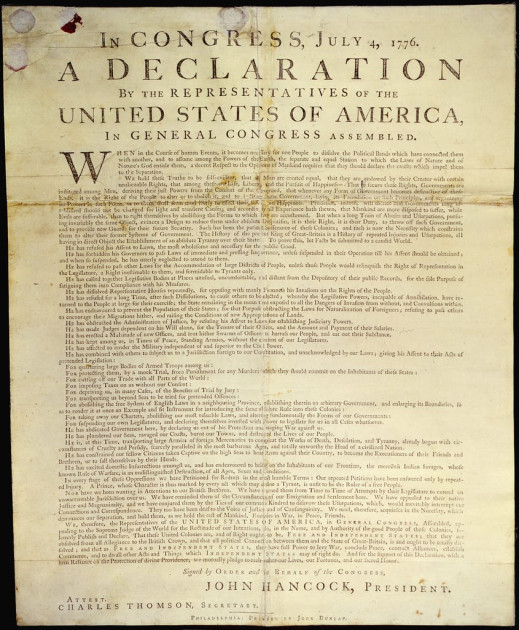

The Equal Rights Amendment passed Congress in 1972 with overwhelming bipartisan support. It needed ratification from 38 states. Within five years, 35 states had ratified. Just three more states and women’s constitutional equality would have been guaranteed.

Fifty-three years later, the ERA still isn’t in the Constitution. Three more states did eventually ratify between 2017 and 2020, but decades after the deadline Congress had set. Whether those late ratifications count remains legally contested, with the outcome uncertain.

That failure reveals something crucial about constitutional change in America. The ERA had presidential support, strong majorities in Congress, overwhelming public approval, and momentum. It still failed. Because constitutional amendments don’t require popular support or even strong majorities – they require extraordinary consensus across an impossibly diverse country over an extended period of time.

America has successfully amended its Constitution 27 times in 236 years. The real story lives in the amendments that failed – the moments when cultural change almost became permanent law, then didn’t. These failed amendments reveal more about American politics than the successful ones ever could.

The Amendment That Would Have Made You Lose Citizenship For Accepting A Royal Title

The Titles of Nobility Amendment passed Congress in 1810 during the Madison administration. It would have automatically stripped American citizenship from anyone who accepted a title of nobility from a foreign power without Congressional consent.

This wasn’t paranoia. European powers regularly tried to influence American officials through titles, honors, and aristocratic recognition. The Founders feared that American democracy could be corrupted through the Old World class system.

Twelve of the thirteen states needed for ratification approved it. Then momentum stopped. No more states ratified. The amendment died one state short.

Why did it fail? America grew confident enough not to care. The War of 1812 proved the United States could stand against European powers. The threat of corruption through foreign titles faded. By the 1820s, the amendment seemed like fighting yesterday’s war.

But the amendment never officially died. Congress didn’t set a ratification deadline. Technically, the Titles of Nobility Amendment is still pending. Some fringe theorists periodically “rediscover” it and claim it secretly passed, usually to argue that some modern politician has inadvertently forfeited citizenship through honorary degrees or awards.

The legal reality is that an amendment proposed in 1810 that couldn’t get ratified in 215 years is effectively dead. But it remains a constitutional zombie – technically alive, practically irrelevant, occasionally reanimated to cause confusion.

When Congress Tried To Ban Child Labor And States Said No

The Child Labor Amendment passed Congress in 1924 after the Supreme Court struck down federal child labor laws as unconstitutional overreach. The amendment would have explicitly given Congress power to regulate child labor nationwide.

Labor reformers expected easy ratification. Child labor was widely recognized as morally wrong and economically exploitative. Photographs of children working in factories and mines had shocked the American conscience.

Twenty-eight states ratified. Ten short of the thirty-six needed. Then ratifications stopped entirely.

The opposition came from an unlikely alliance. Southern agricultural interests opposed federal interference with farming practices that relied on child workers. Religious conservatives worried about government usurping parental authority. States’ rights advocates saw it as federal overreach into state matters.

The Great Depression shifted priorities. With adult unemployment at 25%, the political energy for child labor reform dissipated. Adults needed the jobs children were taking.

Here’s the twist: The amendment became unnecessary. The Supreme Court reversed its earlier decisions and allowed federal child labor regulation under the Commerce Clause. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 accomplished through statute what the amendment would have done through constitutional change.

This pattern repeats throughout constitutional history. Sometimes you don’t need an amendment because courts change their interpretation to permit what they previously prohibited. Whether that’s healthy constitutional evolution or judicial overreach depends on your view of how much power courts should have to effectively amend the Constitution without going through Article V procedures.

The ERA: How Phyllis Schlafly Stopped Women’s Constitutional Equality

The Equal Rights Amendment’s language was simple: “Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

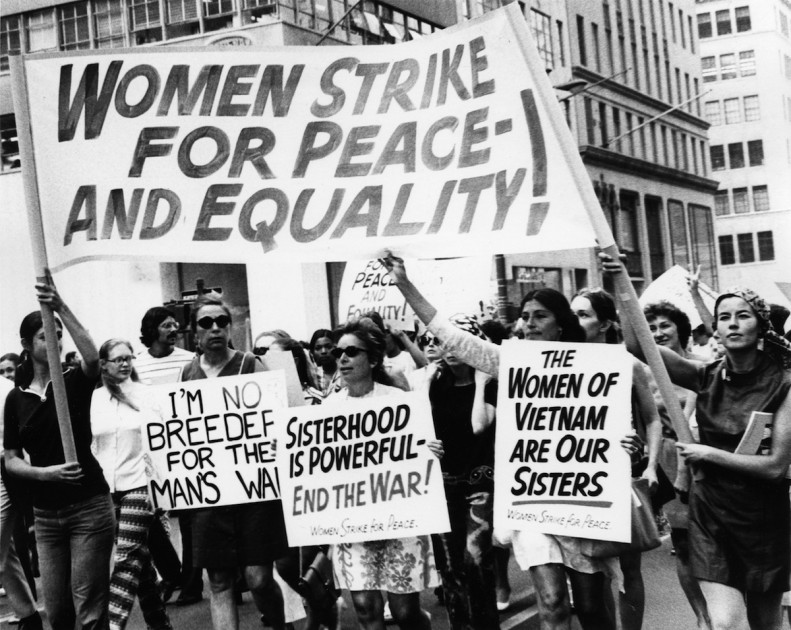

Congress passed it in 1972 with huge majorities – 354-24 in the House, 84-8 in the Senate. Both parties supported it. Presidents from both parties endorsed it. Thirty states ratified within the first year. Passage seemed inevitable.

Then Phyllis Schlafly started organizing. Her STOP ERA campaign argued the amendment would eliminate women’s privileges – exemption from the draft, beneficial divorce and custody laws, single-sex bathrooms. She framed women’s rights as a threat to traditional family structures.

By 1977, 35 states had ratified – just three short. Then momentum collapsed. Five states voted to rescind their ratifications (though the legal validity of rescissions is disputed). No new states ratified despite deadline extensions.

The ERA died in 1982 when the ratification deadline expired. But the fight didn’t end. Three more states – Nevada, Illinois, and Virginia – ratified between 2017 and 2020, bringing the total to 38.

So is the ERA now part of the Constitution? Nobody knows. Proponents argue the deadline was arbitrary and late ratifications should count. Opponents argue the deadline matters and the entire process must restart. The issue sits in legal limbo, with courts likely to eventually decide.

The ERA’s failure despite overwhelming support reveals a crucial dynamic. Constitutional amendments can be stopped by well-organized minority opposition in a handful of states. Ratification requires three-fourths of states, meaning opponents only need to block 13. In practice, that means a regional minority can prevent constitutional change the nation wants.

The Amendment That Would Have Required A Referendum Before Declaring War

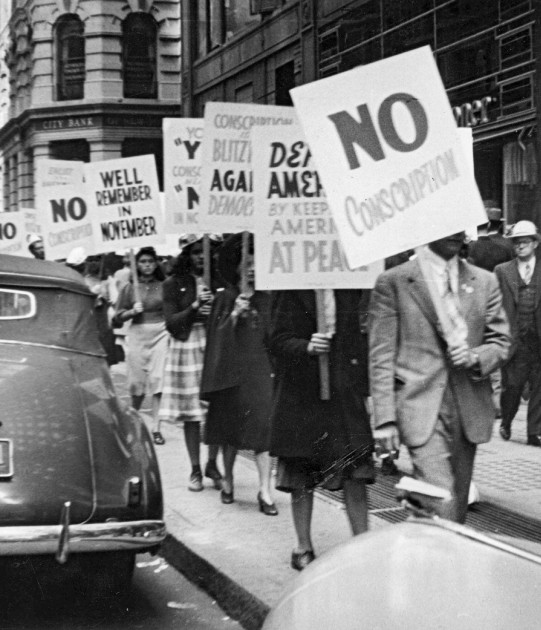

January 1938. Europe was sliding toward another world war. Americans remembered the catastrophe of World War I and wanted no part of a second European conflict.

Representative Louis Ludlow proposed a constitutional amendment requiring a national referendum before Congress could declare war, except in case of invasion. American entry into war would require not just Congressional approval but direct popular vote.

The Ludlow Amendment came terrifyingly close. The House voted 209-188 to discharge it from committee – just seven votes made the difference. If it had reached the floor for a full vote, it likely would have passed the House and possibly the Senate.

President Franklin Roosevelt personally lobbied against it, warning it would cripple American foreign policy and embolden enemies by signaling America couldn’t act quickly. Pearl Harbor arrived three years later, proving his point about the dangers of inflexibility.

But the Ludlow Amendment raises profound questions. Why shouldn’t war require popular approval? Sending Americans to die is the gravest decision government makes. Shouldn’t the people decide?

The counterargument is that representative democracy exists precisely because direct democracy is impractical for complex decisions. Foreign policy moves quickly. Referendum campaigns take months. By the time a vote happened, the crisis requiring military response might have passed or escalated beyond control.

Modern relevance appears everywhere. America hasn’t formally declared war since 1941, but has waged military operations in dozens of countries. The War Powers Act was supposed to limit presidential war-making. It hasn’t. Would the Ludlow Amendment have prevented unauthorized military actions, or just made all military action impossible?

The Amendment That Would Have Abolished Income Tax And Most Federal Programs

The Liberty Amendment emerged from business circles in the 1950s and 60s. It proposed abolishing the income tax, estate tax, and gift tax while prohibiting federal involvement in business or agriculture “not required for the operation of government.”

This wasn’t fringe activism – it had serious backing. Wyoming and Texas state legislatures passed resolutions calling for the amendment. Wealthy businessmen funded campaigns in multiple states. Conservative intellectuals provided theoretical justification.

The amendment would have fundamentally restructured American government. No income tax meant no Social Security, no Medicare, no federal education funding. The federal government would shrink to roughly its 1900 size, handling only defense, foreign policy, and basic administration.

It died because Americans liked the programs income tax funded more than they hated the tax itself. Even conservative voters wanted Social Security and Medicare for themselves, even if they opposed “big government” in the abstract.

The Liberty Amendment reveals the permanent tension in American politics. Voters consistently say they want smaller government and lower taxes. They consistently oppose cutting specific programs that benefit them. Any amendment requiring actual trade-offs between taxation and services faces that contradiction.

Modern echoes appear in every election. Tea Party movements, libertarian campaigns, and anti-tax advocacy all channel the Liberty Amendment’s spirit. But none push for constitutional amendment anymore because they learned the lesson of the 1960s: Americans won’t vote to eliminate their own benefits, no matter how much they claim to oppose government spending.

The Balanced Budget Amendment That Failed By One Vote

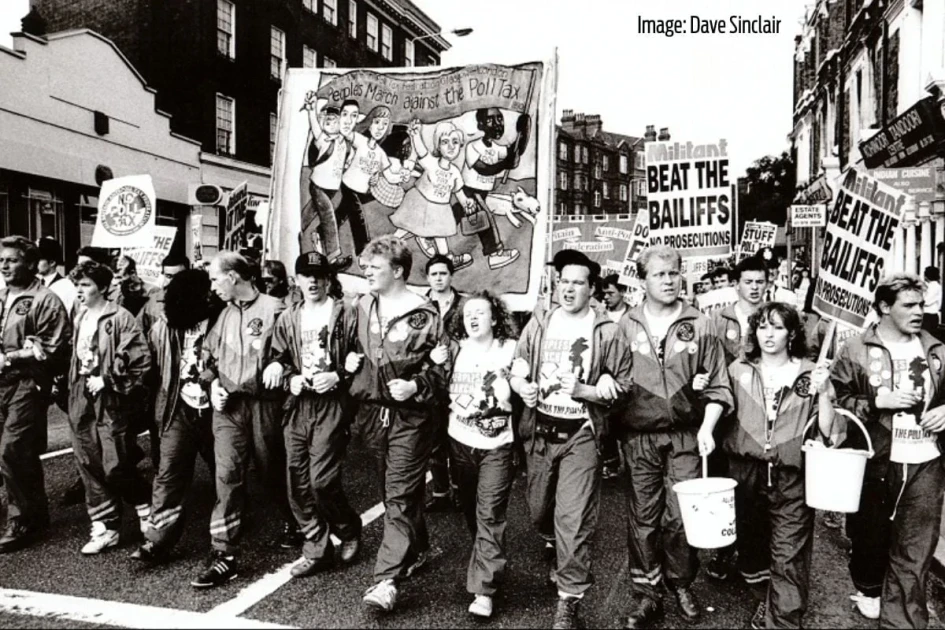

The Balanced Budget Amendment requires the federal budget to balance except during war or national emergency declared by supermajority. Various versions have been proposed since the 1970s.

The closest it came to passage was 1995. The House passed it 300-132. The Senate voted 65-35 – one vote short of the two-thirds needed. Senator Mark Hatfield of Oregon cast the deciding vote against it, ending his political career but preventing what he believed would be economic catastrophe.

Public support for balanced budget requirements consistently polls above 70%. Yet Congress can’t pass it. Why?

The hypocrisy is spectacular and bipartisan. Republicans push balanced budget amendments when Democrats spend, then explode deficits through tax cuts when they control government. Democrats push fiscal responsibility when Republicans cut taxes, then propose massive spending when they control government.

Neither party actually wants their hands tied. Balanced budgets sound responsible in the abstract. In practice, they’d require either massive tax increases or devastating program cuts or both. No politician wants to campaign on “I’ll amend the Constitution to force myself to make the difficult choices I currently avoid.”

The amendment also faces legitimate economic objections. Keynesian economics argues that deficit spending during recessions prevents depressions. Requiring balanced budgets would prevent counter-cyclical fiscal policy and turn recessions into catastrophes.

Whether that’s correct is debatable. What’s not debatable is that balanced budget amendments keep failing despite massive public support because the politicians who’d have to pass them don’t actually want them. It’s performative fiscal responsibility – claiming to support what you know will never happen.

When Congress Tried To Impose Term Limits On Itself

Term limits for Congress poll between 70% and 80% consistently across decades and across partisan lines. Americans overwhelmingly want to limit how long representatives and senators can serve.

The typical proposal sets 12 years as the maximum – six House terms or two Senate terms. After that, you’re done. No career politicians, no permanent political class, no entrenchment.

Congress has never passed a term limits amendment. They’ve never even come close.

The reason is obvious: Members of Congress would have to vote to eliminate their own jobs. The incentives are entirely wrong. The people most interested in term limits are voters. The people least interested are the politicians who’d have to pass them.