President Trump announced on his social media platform that Americans can expect checks for $2,000, funded by “massive Tariff Income pouring into our Country from foreign countries.” The money would go to “low and middle income USA Citizens” – direct payments from trade policy revenue.

The proposal raises two distinct questions that deserve examination. First, does the arithmetic support sending $2,000 to every qualifying American? Second, does the president have authority to redistribute tax revenue without Congressional appropriation?

The answers complicate what sounds like a straightforward promise. They also reveal how modern governance tests constitutional boundaries in ways the Framers likely didn’t anticipate.

Whether this represents bold executive leadership or constitutional overreach depends largely on your view of presidential power. The math, at least, is less ambiguous.

Running The Numbers On Tariff Revenue

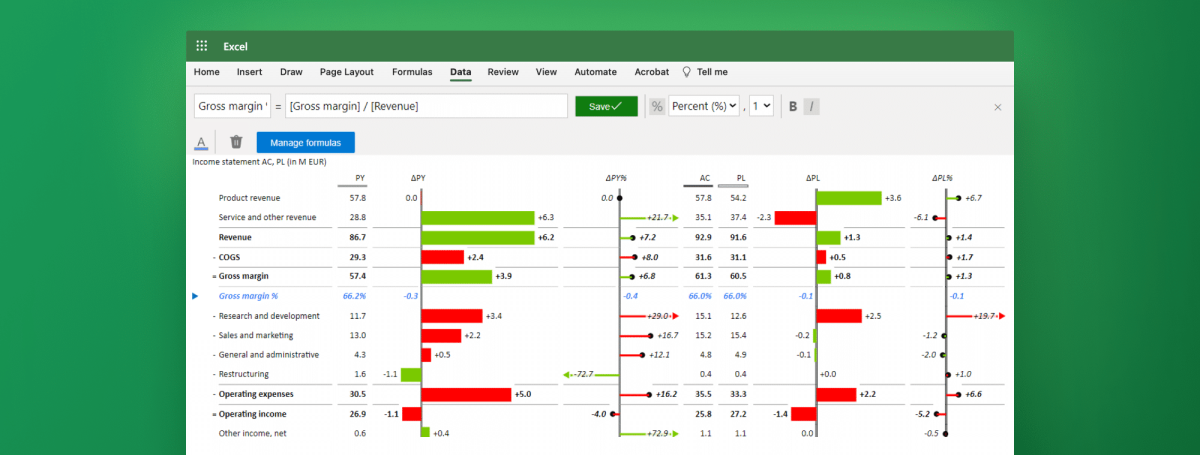

Trump’s tariffs have generated approximately $263 billion through the end of 2025, according to Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimates. That figure represents the total revenue available if every dollar were redirected to rebate checks.

The next question: How many Americans qualify as “low and middle income”? There are about 163.6 million tax filers this year. The definition matters enormously.

If “middle income” means under $200,000 annually – a generous threshold that would include most filers – that’s about 151 million people. Dividing $263 billion by 151 million yields $1,742 per person. Below the promised $2,000, and only achievable if the entire tariff revenue stream gets redirected to checks.

Lower the threshold to around $100,000 – closer to double the actual U.S. median income of $84,000 – and you need approximately $249 billion for about 124 million filers. That’s nearly the entire collected amount.

The arithmetic works only if “middle income” gets defined well below what most Americans would recognize as middle class, or if significantly less than $2,000 per person gets distributed. Neither outcome matches the announcement’s framing, though both remain possible if the proposal advances.

The Constitutional Question About Spending Authority

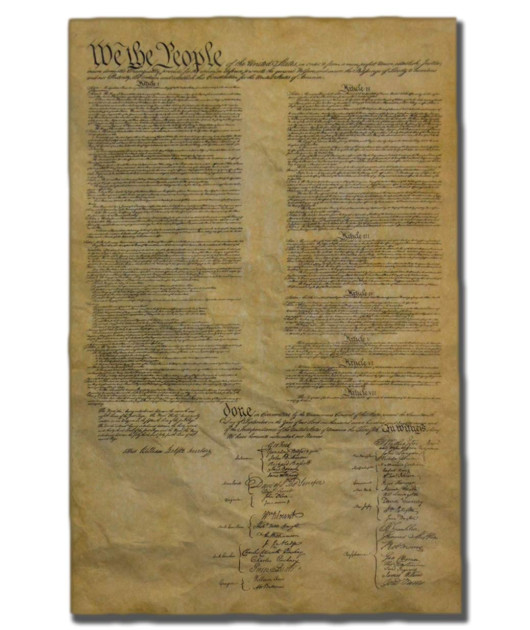

Before examining whether the numbers work, there’s a threshold legal question: Can the president unilaterally decide to distribute tax revenue as direct payments?

The Constitution assigns this power to Congress. Article I, Section 9 states: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” This provision gives Congress – not the president – control over how tax revenue gets spent.

Trump’s announcement appears to assume either Congressional authorization for this redistribution, or that Congress won’t block executive action to implement it. The proposal’s viability depends almost entirely on which scenario unfolds.

Presidential administrations of both parties have tested the boundaries of spending authority, particularly during divided government. Whether this represents normal executive initiative or genuine constitutional overreach is debatable – legal scholars and political partisans would offer sharply different assessments.

The immediate practical question is whether Congress will appropriate funds for this purpose. Without that appropriation, the proposal faces a significant legal obstacle regardless of one’s views on executive power.

Examining Who Actually Pays Tariffs

Understanding where tariff revenue originates matters for evaluating the proposal’s substance. Tariffs aren’t paid by foreign governments – they’re paid by American importers, who typically pass those costs to consumers through higher prices.

Goldman Sachs estimates that by year’s end, approximately 55% of tariff revenue will have come from consumers paying more for imported goods. Another 22% represents costs absorbed by U.S. businesses. Combined, that’s 77% of collected revenue that originated with American consumers and companies.

This creates an interesting economic dynamic: The proposal would use money collected from Americans through higher prices to send checks to (some) Americans, while framing it as money from “foreign countries.”

Supporters would argue this amounts to smart redistribution – taking from those who can afford imported goods and giving to middle and lower income Americans.

Critics would characterize it as taking money from Americans, running it through federal bureaucracy, then returning a fraction while claiming credit for generosity.

Both interpretations fit the same underlying facts. The economic reality is that most of the money originates domestically, regardless of how one views the policy wisdom of redistributing it.

The DOGE Precedent From Earlier This Year

This isn’t the first time in 2025 the administration has proposed substantial direct payments to Americans. During the height of the Department of Government Efficiency initiative, Americans were told they might receive as much as $5,000 from projected government spending cuts.

The DOGE website continues to claim $214 billion in savings, which would translate to roughly $1,300 per taxpayer if fully redistributed. Those payments haven’t materialized. Government spending has actually increased more than 6% compared to the same point last year, according to Brookings Institution data.

Whether the DOGE payments were always intended as aspirational goals rather than firm commitments, or whether they represented overpromising on achievable results, remains a matter of perspective. What’s empirically clear is that the checks haven’t arrived despite the continuing claims of substantial savings.

This recent history provides context for evaluating the tariff rebate proposal. It suggests either that direct payment proposals face significant implementation barriers, or that they serve political purposes beyond their literal fulfillment. Observers from different political perspectives would emphasize different conclusions from this pattern.

Timing And The Supreme Court’s Tariff Decision

The Supreme Court is currently considering whether Trump has legal authority to impose these tariffs without explicit Congressional approval. Lower courts have ruled he lacks that authority. The constitutional question is substantial and involves interpretations of executive power that have evolved considerably over recent decades.

Trump’s $2,000 check announcement arrives while this litigation proceeds. The timing creates an interesting dynamic: The proposal frames tariff revenue as directly benefiting Americans, which potentially influences public perception of the underlying legal dispute.

If the Court rules that Trump lacks authority to impose tariffs unilaterally, that decision would eliminate not just the tariffs but also the revenue stream funding these proposed payments.

This connection between the legal question and the payment proposal is difficult to ignore.

Whether this constitutes appropriate public advocacy for the president’s legal position or inappropriate pressure on judicial decision-making depends on one’s view of how executive and judicial branches should interact. Presidents have historically made public arguments for their legal positions while cases proceed. Whether this instance crosses lines is a judgment call.

The Court will decide the case based on statutory interpretation and constitutional law. Whether public opinion about potential payment benefits influences that legal analysis is unknowable from outside the Court’s deliberations.

Defining “Middle Income” And The Threshold Problem

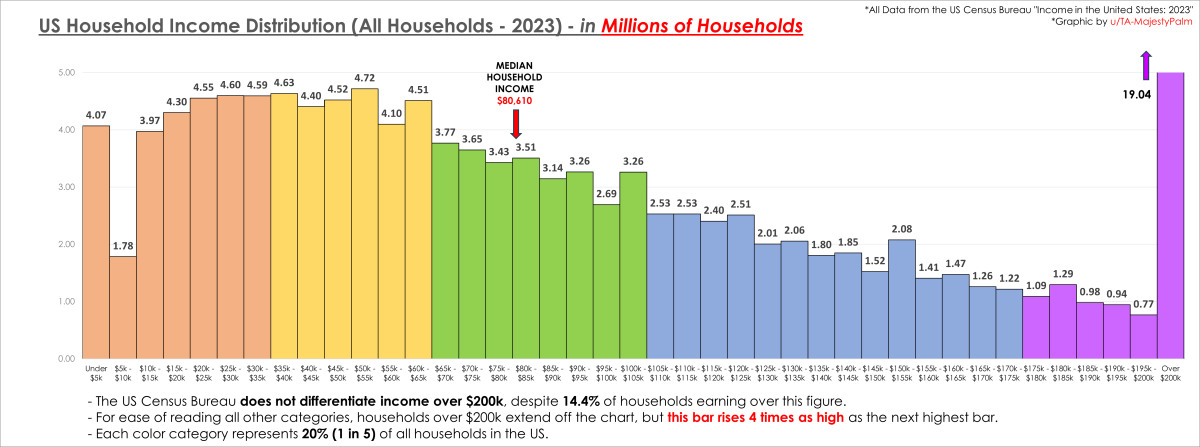

Trump’s announcement describes recipients as “low and middle income USA Citizens” without specifying income thresholds. That ambiguity matters significantly for determining whether the proposal is mathematically feasible.

Most Americans consider themselves middle class, regardless of their actual income. The U.S. median household income in 2024 was approximately $84,000. Many earning $100,000 or even $150,000 would reasonably consider themselves middle income, especially in high-cost regions.

If the definition aligns with self-perception, the revenue falls dramatically short. If it gets defined more narrowly – perhaps under $50,000 or $60,000 – the math becomes more achievable but excludes many who expected to qualify based on the announcement’s language.

This isn’t necessarily deceptive. Political proposals frequently use imprecise language that gets clarified during implementation. But the gap between broad public expectations and realistic definitions creates a predictable disappointment when details emerge.

How this plays out politically depends entirely on execution. Clear communication about thresholds could manage expectations. Vague definitions that get quietly narrowed after initial excitement would generate different reactions.

The Economics of Redistribution Through Tariffs

Setting aside political considerations, there’s an economic question worth examining: Does redistributing tariff revenue to lower and middle income Americans make policy sense?

Tariffs function as regressive taxation – they hit lower-income Americans harder proportionally because they spend more of their income on consumer goods. If tariff revenue gets partially redistributed to those same lower-income Americans, it could offset some of that regressivity.

From this perspective, the proposal represents a form of progressive redistribution funded by what amounts to a consumption tax. That’s not inherently unreasonable as policy design, though economists would debate its efficiency compared to alternatives.

The counterargument is that the most efficient approach would be avoiding the tariffs altogether, allowing Americans to keep money in their pockets rather than extracting it through higher prices and returning a fraction. That eliminates the administrative costs and distribution inefficiencies of the redistribution system.

Both positions have economic logic supporting them. The choice between them involves value judgments about government’s role in managing market outcomes, not just mathematical optimization.

Historical Context: Direct Payments As Policy Tool

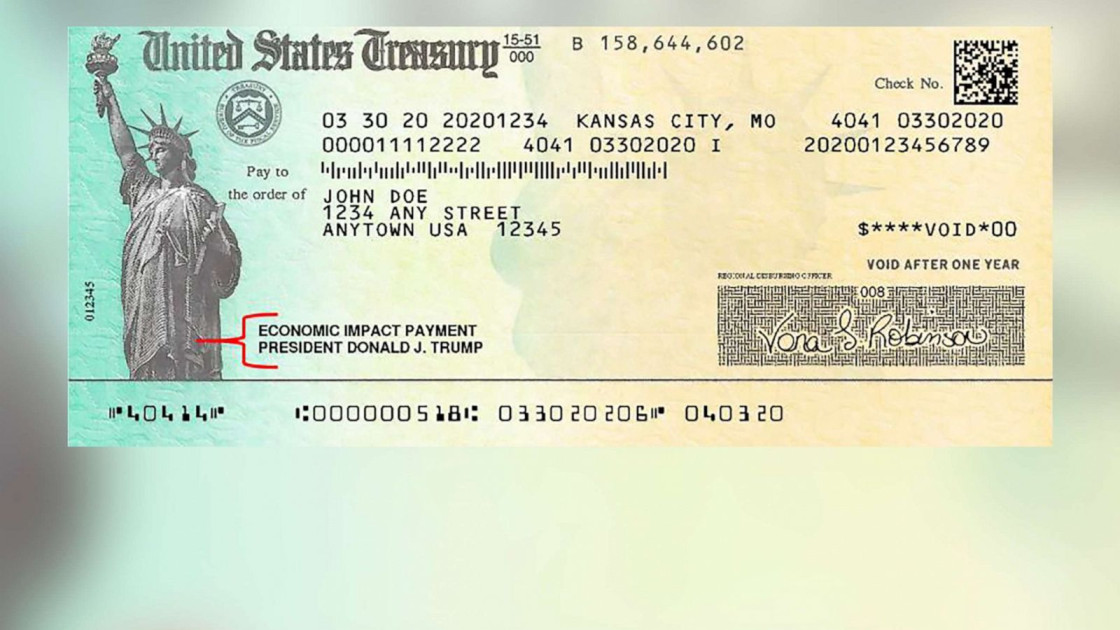

Direct government payments to citizens aren’t novel. The 2020 pandemic stimulus checks, the 2008 economic stimulus payments, and even the Bush-era tax rebates all followed similar logic – putting money directly into Americans’ hands for either economic stimulus or relief purposes.

Those programs had Congressional authorization and specific statutory frameworks. They also faced criticism about effectiveness, distribution fairness, and fiscal responsibility. But they established precedent that direct payments can serve legitimate policy goals when properly authorized.

The tariff rebate proposal differs primarily in its funding mechanism and the unclear path to Congressional appropriation. Whether those differences make it categorically distinct from prior programs or just another variation depends partly on whether authorization eventually materializes.

Historical precedent suggests direct payment programs generate both public enthusiasm and implementation challenges. They’re politically popular but administratively complex. They provide immediate visible benefit but raise questions about long-term fiscal sustainability.

Congressional Authority And The Path Forward

Whether this proposal advances depends almost entirely on Congressional action. If Congress appropriates funds for tariff-funded rebate checks, the program becomes legally straightforward regardless of one’s view of its policy merits.

If Congress doesn’t appropriate funds, the administration would need to identify existing statutory authority permitting this redistribution, or proceed without clear authorization and face likely legal challenges. Past administrations have sometimes tested these boundaries, with mixed results in courts.

The current Congressional leadership hasn’t indicated support for or opposition to this specific proposal. That silence leaves considerable uncertainty about whether the legislative branch will enable the executive’s plan.

How this uncertainty resolves will reveal important information about the current state of separation of powers and Congressional willingness to assert its appropriations authority. Those outcomes matter beyond this specific proposal – they set precedents for future executive spending initiatives.