The Second Amendment contains 27 words. Those words have generated centuries of constitutional conflict, dozens of Supreme Court cases, and fundamentally different interpretations of what “the right to keep and bear arms” actually means. Some cases changed everything. Others revealed how deeply Americans disagree about guns, rights, and government power.

This ranking counts down the most controversial Second Amendment cases in American legal history – from early disputes about militia service to modern battles over concealed carry and drug user prohibitions. Controversy here means cases that sparked intense public debate, produced sharply divided courts, dramatically shifted legal doctrine, or revealed fundamental tensions about constitutional rights.

These aren’t necessarily the most important cases legally. They’re the ones that made Americans argue loudest about what the Constitution says, what the Founders meant, and whether gun rights should expand or contract in modern society.

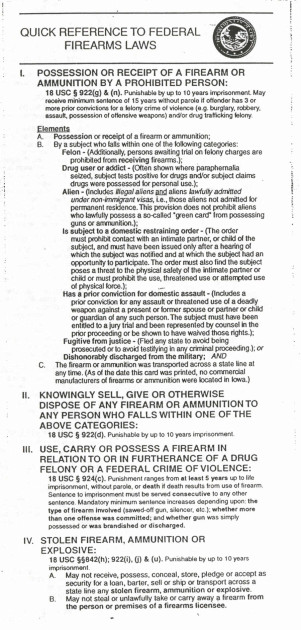

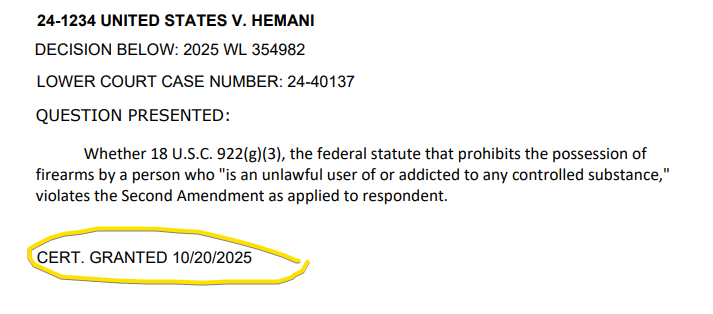

10. Hemani v. United States (Upcoming) – The Drug User Gun Case That Tests Second Amendment Limits

The Issue: Can the federal government prohibit people who use illegal drugs from possessing firearms, even if they’ve never been convicted of drug crimes?

Why It’s Controversial: This case forces courts to determine whether Second Amendment protections extend to people engaged in illegal conduct. After Bruen established that gun regulations must align with historical tradition, it’s unclear whether drug use – a category that didn’t exist in 1791 – justifies disarmament.

The federal law prohibits firearm possession by unlawful drug users. Patrick Daniels, the defendant in the Fifth Circuit case that generated this issue, used marijuana regularly and possessed a firearm. He was prosecuted under 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(3).

Post-Bruen, his attorneys argued that historical tradition doesn’t support disarming people for drug use absent criminal conviction. The government countered that dangerousness and substance abuse have long justified firearm restrictions.

The Constitutional Tension: If courts strike down the drug user prohibition, millions of Americans who use marijuana (legal in many states but federally illegal) could possess guns without federal restriction. If courts uphold it, they establish that Congress can create categories of prohibited persons based on conduct rather than convictions – potentially opening door to broader disarmament.

The case hasn’t been decided yet, but it represents the cutting edge of post-Bruen litigation. It tests whether the historical standard actually constrains Congress or whether courts will find ways to uphold most existing gun regulations through creative historical analogies. The controversy comes from uncertainty – nobody knows whether Bruen’s framework actually requires striking down longstanding prohibitions or whether courts will distinguish drug users from law-abiding citizens Bruen was designed to protect.

9. Kachalsky v. County of Westchester (2012) – The Concealed Carry Case That Bruen Overruled

The Issue: Can states require gun owners to demonstrate “proper cause” – a specific need beyond general self-defense – before issuing concealed carry permits?

Why It’s Controversial: This Second Circuit case upheld New York’s highly restrictive concealed carry licensing scheme. The court ruled that intermediate scrutiny applied and that New York’s proper cause requirement didn’t violate the Second Amendment because it still allowed some people to carry guns for self-defense.

Alan Kachalsky applied for a concealed carry permit. New York required him to show “proper cause” – meaning a special need for self-protection distinguishable from the general public. Kachalsky couldn’t demonstrate such need, so his application was denied.

The Second Circuit held that this was constitutional. States could require individualized showings of need before allowing public carry. The reasoning reflected pre-Bruen doctrine: government has strong interest in public safety, restrictions that still allow some people to carry pass constitutional muster.

The Constitutional Tension: Kachalsky represented the high-water mark of permissive gun regulation. It established that gun rights outside the home received less protection than rights inside the home. States could restrict public carry extensively as long as some path to permits existed – even if that path was effectively closed to average citizens.

8. Silveira v. Lockyer (2002) – The Pre-Heller Case That Said There’s No Individual Right

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment protect an individual right to possess firearms, or does it only protect a collective right related to militia service?

Why It’s Controversial: Before Heller, federal circuits disagreed sharply about what the Second Amendment meant. Silveira represented the “collective right” interpretation – the view that the Second Amendment only protected states’ rights to maintain militias, not individuals’ rights to own guns.

Gary Silveira challenged California’s assault weapons ban, arguing it violated his Second Amendment rights. The Ninth Circuit rejected his claim, holding that the Second Amendment doesn’t confer an individual right to possess firearms unconnected to militia service.

Judge Reinhardt’s opinion stated: “The Second Amendment was adopted to protect the right of the people of each of the several States to maintain a well-regulated militia.” Individual gun ownership unrelated to militia service received no constitutional protection.

The Constitutional Tension: Silveira represented constitutional doctrine that existed for decades before Heller. Multiple circuits had adopted similar reasoning. The collective right interpretation meant that virtually any gun regulation short of completely disarming state militias was constitutional.

From this perspective, the Second Amendment was about federalism – protecting states from federal disarmament – not about individual liberty. That made it functionally irrelevant to modern gun control debates since states weren’t trying to maintain 18th-century style militias.

Silveira is controversial because it reflects a constitutional interpretation that was mainstream until Heller rejected it. Millions of Americans, many judges, and numerous legal scholars believed for decades that the Second Amendment didn’t protect individual gun ownership. Heller declared that interpretation wrong – but that doesn’t erase the fact that Silveira represented legitimate constitutional doctrine for generations.

7. Caetano v. Massachusetts (2016) – The Stun Gun Case That Clarified “Arms”

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment protect the right to possess stun guns and other non-lethal self-defense weapons?

Why It’s Controversial: Jamie Caetano obtained a stun gun for self-protection from an abusive ex-boyfriend. Massachusetts banned stun guns entirely. She was prosecuted for possession.

The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court upheld her conviction, reasoning that stun guns didn’t exist when the Second Amendment was adopted in 1791, so they weren’t protected “arms.” The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously reversed in a per curiam opinion.

The Court held that the Second Amendment’s protection extends to arms that were not in existence at the founding. The decision quoted Heller: the Second Amendment “extends to arms that were not in existence at the time of the founding.”

The Constitutional Tension: Caetano resolved a question Heller left open: does Second Amendment protection extend only to firearms that existed in 1791, or does it protect modern weapons technology? Massachusetts argued for the restrictive reading – only 18th-century weapons receive protection.

The Supreme Court rejected that cramped interpretation. But the opinion didn’t clarify how far protection extends. Does it cover all bearable arms? Only those commonly used for lawful purposes? What about weapons more dangerous than those available in 1791?

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed, suggesting the outcome wasn’t close. But Justice Alito’s concurrence (joined by Justice Thomas) went much further, criticizing the Massachusetts court’s reasoning comprehensively and suggesting broader Second Amendment protection than the per curiam opinion established.

The controversy comes from what Caetano implies but doesn’t resolve: if stun guns are protected despite not existing in 1791, what about other modern weapons? Semi-automatic rifles? High-capacity magazines? The case opened questions it didn’t answer, leaving room for continued litigation about which modern arms receive constitutional protection.

6. United States v. Miller (1939) – The Sawed-Off Shotgun Case That Confused Everyone

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment protect the right to possess sawed-off shotguns?

Why It’s Controversial: This is the Supreme Court’s first major Second Amendment decision, and it’s been cited by both sides of the gun debate for 85 years despite being remarkably unclear about what it actually holds.

Jack Miller was indicted for transporting a sawed-off shotgun across state lines in violation of the National Firearms Act. He challenged the law as violating the Second Amendment. The district court agreed and dismissed the indictment. The government appealed directly to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court reversed, holding that the Second Amendment protects only weapons “in common use” for militia purposes. Since the government presented no evidence that sawed-off shotguns had “reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia,” they weren’t protected.

The Constitutional Tension: Miller has been interpreted in completely opposite ways. Gun control advocates read it as establishing that Second Amendment protection extends only to weapons useful for militia service – meaning military-style weapons get protection while civilian weapons don’t.

Gun rights advocates read it as protecting military-useful weapons – meaning AR-15s and similar rifles are clearly protected since they’re exactly the kind of weapons militias would use.

Both interpretations cite the same opinion. The confusion stems from Miller’s ambiguous language and the fact that Miller himself didn’t appear (he’d been murdered before the Supreme Court heard the case), so the Court only heard the government’s argument.

Miller is controversial because it’s simultaneously cited as supporting gun control and gun rights. For decades before Heller, courts used Miller to uphold gun regulations by reading it as limiting Second Amendment protection to militia-related purposes. After Heller, gun rights advocates argue Miller actually supports broad protection for military-style weapons.

The case remains controversial because its actual holding is unclear. Did it adopt a collective right interpretation? An individual right tied to militia service? Does “common use” mean commonly owned by civilians or commonly useful to militias? The opinion doesn’t clarify, leaving 85 years of competing interpretations.

5. McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010) – Incorporation and the Battle Over Precedent

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment apply to state and local governments through the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause?

Why It’s Controversial: Two years after Heller recognized an individual right to possess firearms in federal enclaves, McDonald extended that right nationwide by incorporating the Second Amendment against the states.

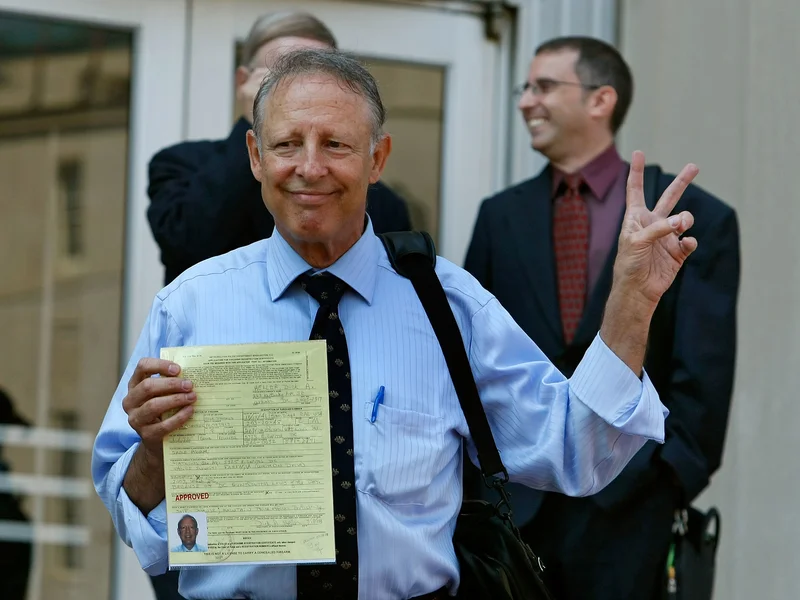

Otis McDonald, a Chicago resident, challenged the city’s handgun ban. Chicago argued that even if Heller recognized a federal individual right, that right didn’t apply to states. The city claimed the Second Amendment was one of the few Bill of Rights provisions not incorporated through the Fourteenth Amendment.

The Supreme Court held 5-4 that the Second Amendment is incorporated through the Due Process Clause. States cannot infringe the individual right to possess firearms for self-defense any more than the federal government can.

The Constitutional Tension: Incorporation debates always involve tensions between original meaning and modern application. Justice Thomas wrote a separate concurrence arguing for incorporation through the Privileges or Immunities Clause instead of substantive due process – a position that could have revolutionized constitutional law but attracted no other votes.

The dissents argued that gun rights differed from other incorporated rights because of federalism concerns and the Second Amendment’s unique militia-related text. They emphasized that gun regulation has traditionally been a state function and that incorporating the right would prevent state experimentation with public safety measures.

By incorporating the Second Amendment, McDonald prevented states from adopting regulations that reflect local values and conditions if those regulations violate the individual right Heller recognized. That homogenization of gun policy across diverse jurisdictions remains contested. The 5-4 vote reflected deep divisions about whether gun rights warrant federal constitutional protection constraining state and local democratic processes. Those divisions persist – McDonald was decided 15 years ago, but controversies about state gun regulations continue litigation today.

4. Printz v. United States (1997) – The Brady Act Case About Federal Commandeering

The Issue: Can Congress require state and local law enforcement officers to conduct background checks on gun purchasers?

Why It’s Controversial: The Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act required state and local law enforcement to perform background checks until a national system was implemented. Sheriff Jay Printz of Montana challenged the law as violating state sovereignty.

The Supreme Court held 5-4 that Congress cannot “commandeer” state officials to enforce federal law. The Tenth Amendment and constitutional structure prevent federal government from compelling state executives to administer federal programs.

Justice Scalia’s majority opinion emphasized that the Constitution’s structure preserves state sovereignty. While Congress can regulate individuals directly through federal law, it cannot force states to implement federal regulatory schemes.

The Constitutional Tension: Printz isn’t directly about gun rights – it’s about federalism and the limits of federal power. But it arose from gun control legislation and significantly affected how federal gun laws could be enforced.

The decision meant that federal gun background check system required federal implementation rather than state commandeering. That affected the feasibility and cost of federal gun regulations since Congress had to build federal infrastructure instead of using existing state law enforcement.

Printz is controversial because it limits federal gun control options while being grounded in federalism principles that transcend gun debates. Gun control advocates saw it as obstructing common-sense regulations. Gun rights advocates saw it as properly limiting federal overreach.

The case reveals tensions between national gun control efforts and constitutional limits on federal power. Even when Congress has authority to regulate an area (like gun sales), structural constitutional principles limit how it can exercise that authority. Printz established that background check requirements couldn’t simply be imposed on states – Congress had to build its own enforcement infrastructure.

That principle extends beyond guns to any federal program. But in the gun context, it meant that federal legislation faced higher implementation costs and practical difficulties, making comprehensive gun control harder to achieve. The controversy comes from whether that’s a feature (protecting state sovereignty) or a bug (obstructing necessary regulation).

District of Columbia v. Heller (2008) – The Case That Changed Everything

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment protect an individual’s right to possess firearms for self-defense in the home, unconnected to militia service?

Why It’s Controversial: This is the most important Second Amendment decision in American history. Before Heller, the constitutional status of gun rights was contested and unclear. After Heller, an individual right to possess firearms for self-defense exists as established constitutional doctrine.

Dick Heller, a D.C. special police officer, challenged the District’s handgun ban and requirement that lawfully owned firearms be kept unloaded and disassembled. The district court dismissed his suit. The D.C. Circuit reversed, holding that the Second Amendment protects an individual right.

The Supreme Court affirmed 5-4 in an opinion by Justice Scalia. The Court held that:

- The Second Amendment protects an individual right to possess firearms

- That right is not unlimited – it extends to weapons “in common use” for lawful purposes

- The right is not connected to militia service

- Complete handgun bans and requirements rendering firearms inoperable for self-defense violate the Second Amendment

The Constitutional Tension: Heller fundamentally reinterpreted the Second Amendment. For decades, many courts and scholars had read it as protecting only a collective right related to militia service. Heller rejected that interpretation based on text, history, and the Amendment’s structure.

Justice Stevens’ dissent (joined by Justices Souter, Ginsburg, and Breyer) argued that the majority ignored the militia clause’s importance and misread historical sources. The dissent maintained that the Second Amendment protects only the right to possess firearms in connection with militia service.

Justice Breyer’s separate dissent argued that even if an individual right exists, it should be subject to interest-balancing tests allowing substantial regulation. The majority rejected that approach, holding that the existence of a constitutional right doesn’t depend on judges’ assessments of its costs and benefits.

Fifteen years later, Heller remains contested. Legal scholars continue debating whether Scalia’s originalist analysis was correct. Lower courts have struggled to apply Heller’s framework. And most gun regulations litigated since Heller haven’t reached clear resolution.

3. New York State Rifle & Pistol Association v. Bruen (2022) – The Concealed Carry Revolution

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment allow states to require applicants for concealed carry licenses to demonstrate “proper cause” – a special need for self-protection beyond general public safety concerns?

Why It’s Controversial: Bruen didn’t just resolve the permit question. It fundamentally changed how courts analyze gun regulations, potentially invalidating decades of state and federal gun control laws.

New York’s licensing scheme required applicants to show “proper cause” for concealed carry permits. Most applicants couldn’t meet this standard – general self-defense didn’t qualify. The state granted permits sparingly, effectively preventing ordinary citizens from carrying guns in public.

The Supreme Court held 6-3 that this violated the Second Amendment. Justice Thomas’ majority opinion established a new analytical framework:

- The Second Amendment protects the right to carry firearms in public for self-defense

- When government regulates conduct within the Second Amendment’s scope, it must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with the Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation

- “Means-end” scrutiny is inappropriate – courts don’t balance Second Amendment rights against government interests

The Constitutional Tension: Bruen rejected the dominant approach lower courts had used to analyze gun regulations post-Heller. Most circuits had applied some form of means-end scrutiny – examining whether regulations substantially burdened Second Amendment rights and, if so, whether they were narrowly tailored to important government interests.

Bruen said that entire approach is wrong. Once conduct falls within the Second Amendment’s scope, the only question is whether the regulation aligns with historical tradition. If no historical analog exists, the regulation violates the Second Amendment.

Justice Breyer’s dissent (joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan) argued that the majority had created an unworkable standard. How do courts determine which historical regulations are analogous to modern laws? How similar must the regulations be? Does the standard require identical historical counterparts or merely similar principles?

Bruen is more controversial than Heller in many ways. Heller established an individual right but left many questions unanswered. Bruen answered those questions in ways that threaten the constitutionality of numerous existing gun laws.

Since Bruen, lower courts have struck down regulations on:

- Prohibitions on gun possession by people under felony indictment

- Prohibitions on gun possession in sensitive places like public transit

- Waiting period requirements

- Age restrictions on gun purchases

- Restrictions on ghost guns

The historical tradition test has proven incredibly difficult to apply. Judges disagree about which historical laws count as analogous. The standard has generated confusion, inconsistency, and continued litigation about virtually every category of gun regulation.

Gun control advocates view Bruen as dangerous judicial activism that prevents democratic regulation of lethal weapons based on invented historical requirements. Gun rights advocates see it as properly constraining government power to infringe constitutional rights.

The controversy is immediate and ongoing. Unlike Heller, which took years for its full implications to develop, Bruen’s impact was instant. Dozens of cases challenging gun regulations under Bruen’s framework have reached courts. The doctrinal revolution Bruen initiated is actively reshaping gun law across America right now.

Bruen ranks #2 because it’s the most disruptive Second Amendment decision in terms of immediate practical impact on gun regulation. Only one case is more controversial.

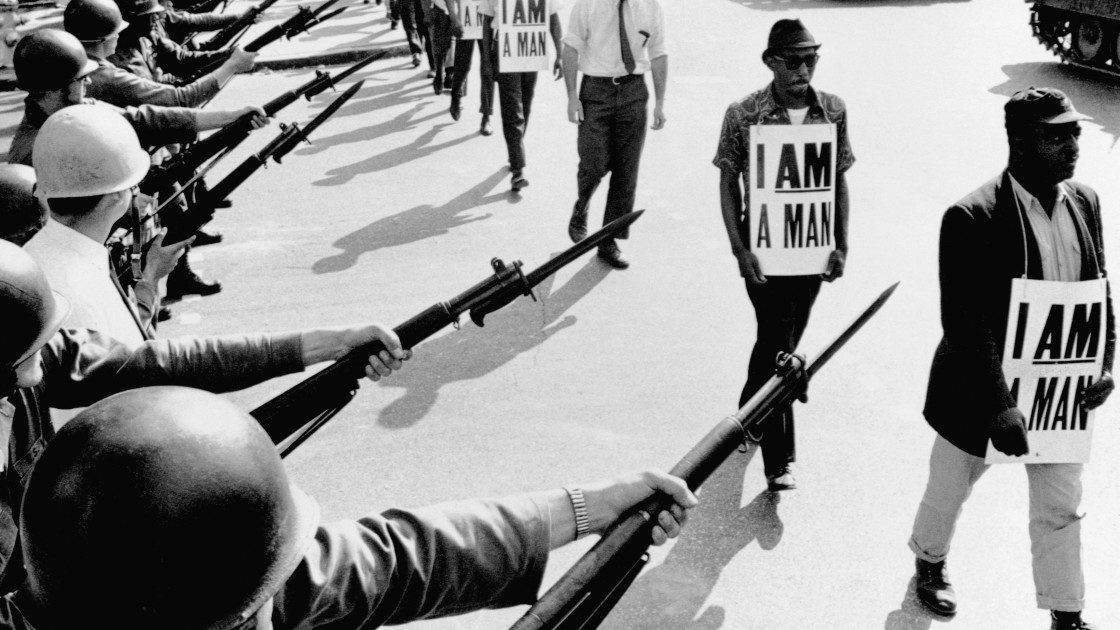

United States v. Cruikshank (1876) – The Post-Civil War Case That Enabled Racist Disarmament

The Issue: Does the Second Amendment protect Black Americans from private violence and state-sanctioned disarmament during Reconstruction?

Why It’s Most Controversial: This is the darkest Second Amendment case in American history. It’s not controversial because of legal doctrine – it’s controversial because it enabled decades of racist violence and discriminatory disarmament of Black Americans in the South after the Civil War.

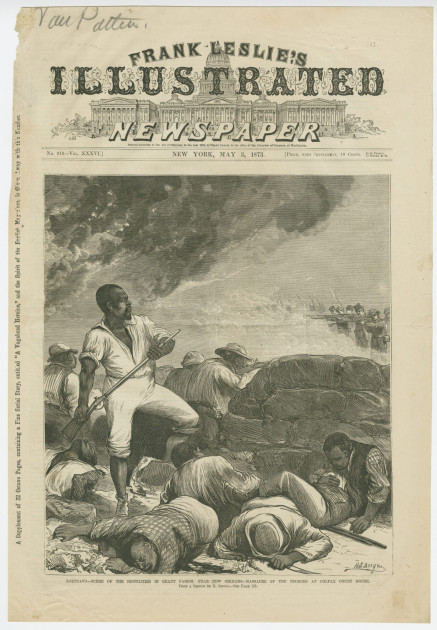

The Colfax Massacre occurred on April 13, 1873, in Louisiana. A disputed gubernatorial election led to tensions between Black Republicans and white Democrats. White supremacists attacked the courthouse where Black citizens had assembled. Estimates suggest 60-150 Black Americans were murdered.

Federal prosecutors charged William Cruikshank and other white supremacists under the Enforcement Act of 1870 with conspiring to deprive Black citizens of their constitutional rights, including their Second Amendment right to bear arms.

The Supreme Court overturned the convictions. Chief Justice Waite’s opinion held that:

- The Second Amendment restricts only federal action, not private conduct or state action

- The right to bear arms exists independent of the Constitution – it’s not granted by the Second Amendment

- Citizens must look to state governments for protection against private violence

- The federal government cannot prosecute individuals for violating other citizens’ constitutional rights

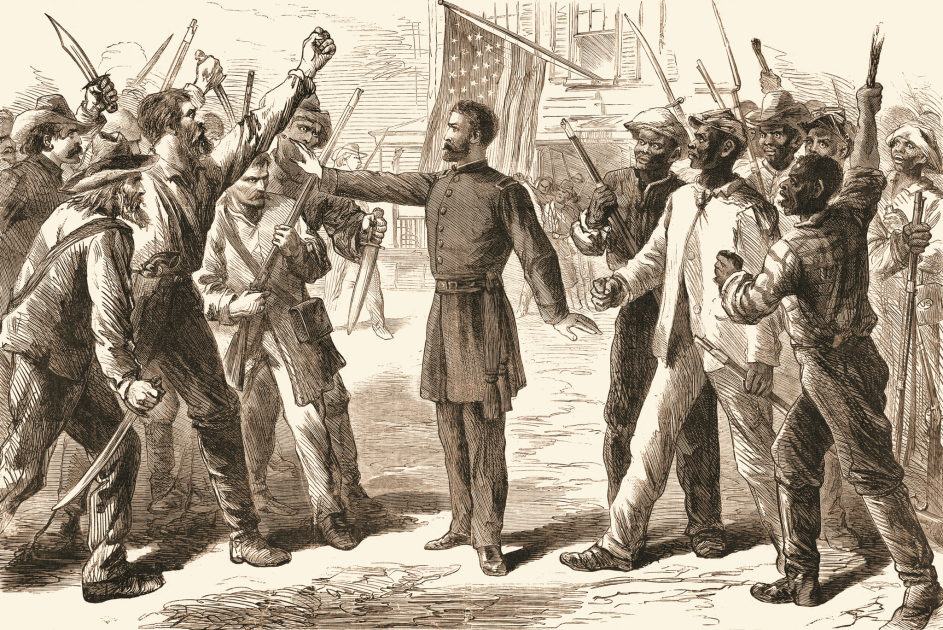

The Constitutional Tension: Cruikshank gutted federal power to protect Black citizens’ civil rights during Reconstruction. The decision meant that when states failed or refused to protect Black Americans from violence – or when states themselves disarmed Black citizens – federal government couldn’t intervene.

The practical result was that Southern states enacted “Black Codes” restricting gun ownership by Black Americans. When Black citizens were attacked by private groups like the Ku Klux Klan, federal authorities couldn’t prosecute the attackers for violating constitutional rights.

Cruikshank established that the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, applied only to federal action. States could restrict gun rights without federal interference. Private individuals could use violence to deprive others of rights without federal prosecution.

Why This Ranks #1: Cruikshank is the most controversial Second Amendment case because its consequences were catastrophic for Black Americans in the South for generations.

The decision enabled:

- State laws disarming Black citizens while allowing white citizens to remain armed

- Private violence against Black Americans without federal remedy

- The collapse of Reconstruction and establishment of Jim Crow segregation

- Decades of lynchings and racial terrorism while federal government stood powerless

The case wasn’t about gun rights as we understand them today. It was about whether federal government could protect newly freed slaves from violence and disarmament by hostile state governments and white supremacists.

The Supreme Court said no. That answer condemned Black Americans to decades of state-sanctioned and privately-inflicted terror.

Cruikshank wasn’t overruled until the 20th century. The incorporation doctrine gradually applied the Bill of Rights to states through the Fourteenth Amendment, eventually leading to McDonald v. Chicago’s explicit incorporation of the Second Amendment in 2010.

But for 134 years – from Cruikshank in 1876 to McDonald in 2010 – the Second Amendment didn’t protect Americans from state infringement. During most of that period, Southern states used that legal reality to disarm and terrorize Black citizens while federal government claimed it couldn’t intervene.

The Historical Context That Makes It Worse

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868 specifically to provide constitutional protection for freed slaves. Section 1 prohibits states from depriving persons of life, liberty, or property without due process and guarantees equal protection.

Congress passed the Enforcement Acts in 1870-1871 to implement the Fourteenth Amendment by criminalizing conspiracies to deprive citizens of constitutional rights. The laws were explicitly designed to allow federal prosecution of Ku Klux Klan violence and state actions disarming Black Americans.

Cruikshank struck down those protections just eight years after the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified and three years after the Colfax Massacre. The Supreme Court read the Civil War Amendments – adopted specifically to empower federal protection of Black citizens’ rights – as not actually providing that protection.

Why It’s Still Relevant

Cruikshank’s reasoning shaped constitutional law for generations. Its holding that the Bill of Rights didn’t apply to states allowed:

- Southern states to suppress Black political participation through violence

- Discriminatory gun laws disarming Black citizens while allowing white citizens to remain armed

- Private racial terrorism without federal remedy

- The establishment of Jim Crow segregation backed by threat of violence against Black Americans who challenged it

The case is taught in constitutional law courses not as good law but as historical shame. It represents the Supreme Court’s complicity in the collapse of Reconstruction and establishment of apartheid in the South.

Modern Second Amendment scholarship increasingly emphasizes the racist history of gun control, pointing to Cruikshank and its aftermath as prime examples of how disarmament has been used as tool of racial oppression. Gun rights advocates cite this history as reason why Second Amendment protection matters – because when government can disarm citizens, it can more easily oppress them.