California banned Glock-style handguns last week. The National Rifle Association sued within days. The lawsuit challenges Assembly Bill 1127 as violating the Second Amendment, arguing that semiautomatic handguns with cruciform trigger bars are “in common use” and therefore protected by the Constitution.

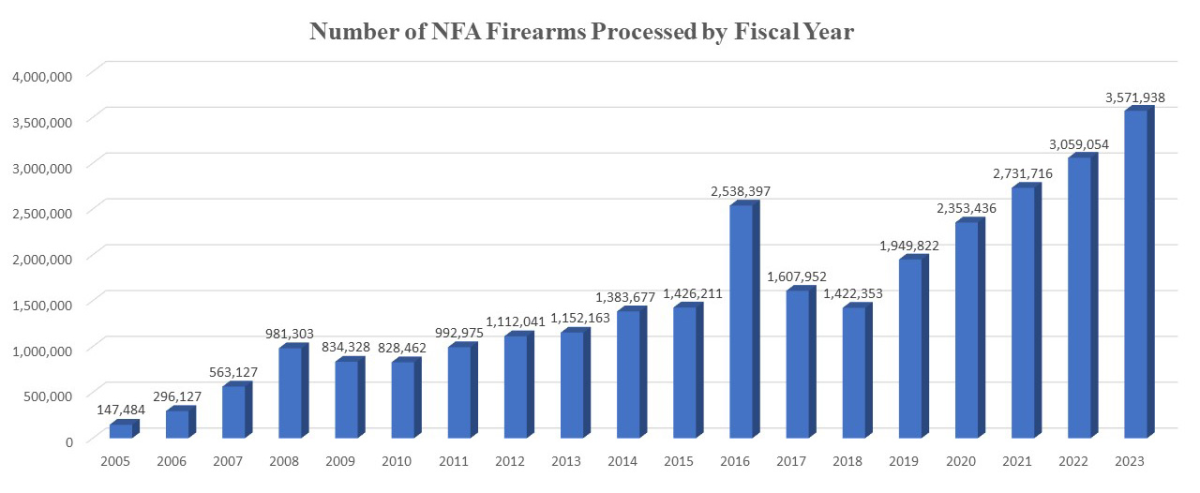

The ban targets firearms that can be readily converted to fully automatic weapons using small mechanical switches – devices the ATF reported increased 570% between 2017 and 2021. California prohibits sale and transfer of these specific pistols starting July 1, 2026. The NRA says the state is banning an entire category of weapons based on design features rather than function.

This lawsuit tests the Supreme Court’s 2022 Bruen decision, which struck down New York’s concealed carry restrictions and reestablished Second Amendment protection for weapons “in common use.” The ruling shifted constitutional analysis away from government interest balancing toward historical tradition of firearm ownership.

What California Actually Banned

Assembly Bill 1127 targets semiautomatic pistols with a specific internal component – a cruciform trigger bar – that allows simple mechanical conversion to automatic fire. The law defines the prohibition narrowly: it applies only to pistols that can be converted “by hand or with common household tools” without “additional engineering, machining, or modification of the pistol’s trigger mechanism.”

The ban excludes hammer-fired semiautomatic pistols and striker-fired pistols without cruciform trigger bars. Law enforcement officers are exempted. The restriction focuses on the specific design feature enabling conversion, not on semiautomatic firearms generally.

California’s rationale centers on conversion devices – small mechanical switches or “auto sears” that replace the pistol’s backplate and convert semiautomatic fire to fully automatic. The ATF reported dramatic increases in law enforcement seizures of these devices, suggesting growing criminal use of converted pistols.

The ban attempts to eliminate the supply of convertible pistols rather than directly banning the conversion devices themselves. Federal law prohibits possession of auto sears and converted firearms, but state law can restrict sale of weapons designed to accommodate them.

The NRA’s Constitutional Argument

The lawsuit claims that Glocks with cruciform trigger bars are “semiautomatic handguns in common use” and therefore protected by the Second Amendment under Bruen. The NRA argues these pistols are functionally identical to other semiautomatic handguns – they fire one round per trigger pull in standard configuration.

The distinguishing design feature – the cruciform trigger bar – doesn’t change the weapon’s function in standard operation. It merely makes conversion to automatic fire easier using a mechanical device. Banning pistols based on this design feature effectively bans a category of semiautomatic firearms based on theoretical capacity rather than actual capability.

The NRA contends that California is attempting to regulate by design feature what it cannot regulate by function. If semiautomatic handguns are “in common use” and therefore protected, banning specific semiautomatic models based on internal design seems to violate Second Amendment protections established in Bruen.

The “common use” standard from Bruen provides the core argument. Millions of Glock pistols exist in civilian hands. They’re widely purchased, legally owned, and used for lawful purposes. That widespread ownership and use arguably satisfies the “in common use” test that triggers Second Amendment protection.

The Conversion Device Reality

Auto sears and conversion switches allow semiautomatic weapons to fire multiple rounds with a single trigger pull – effectively converting them to automatic weapons. Federal law strictly prohibits possession of these devices. Converting a lawful semiautomatic firearm to automatic fire violates federal law.

The ATF’s 570% increase in seized conversion devices between 2017 and 2021 suggests growing criminal and illegal use. These devices enable criminals to convert commercially available semiautomatic pistols into functionally automatic weapons, dramatically increasing firepower for illegal purposes.

But California’s ban doesn’t directly prohibit the conversion devices themselves – federal law already does that. Instead, it prohibits sale of the specific pistols that can be converted using these devices. The logic is that reducing availability of convertible pistols reduces opportunities for illegal conversion.

The strategy treats design features as proxies for criminal risk. Pistols with cruciform trigger bars are riskier than other semiautomatic handguns because criminals can convert them more easily. Therefore, California restricts their sale to civilians.

The Constitutional Question

Supreme Court precedent gives states authority to regulate weapons absent a specific constitutional violation. States can ban certain weapons categories – fully automatic firearms, sawed-off shotguns, other arms not typically possessed by civilians.

But Bruen shifted the analysis. States must now justify restrictions by reference to historical tradition of firearm regulation. A modern regulation restricting weapons must align with how the Founders or 19th century legislators treated similar weapons.

Glocks didn’t exist in 1791 or during the 19th century. Conversion devices are modern technology. How do courts apply historical tradition analysis to weapons and technologies that didn’t exist historically?

The NRA’s argument focuses on functional equivalence: Glocks with cruciform trigger bars function identically to other semiautomatic handguns in standard operation. If the Founders protected the right to possess semiautomatic weapons (a legal category that didn’t exist in 1791 but has been protected since the late 20th century), then banning specific semiautomatic models based on design features seems to violate that protection.

California’s argument would likely emphasize state police powers to regulate dangerous instrumentalities and public safety. The state can restrict weapons designed for easy conversion to automatic fire if such weapons present heightened public safety risks. The focus would be on the design feature’s criminal utility rather than the weapon’s lawful use capacity.

The Bruen Framework Under Pressure

Bruen rejected the interest-balancing approach that characterized Second Amendment jurisprudence before 2022. Courts could no longer uphold weapons restrictions simply because states claimed important public safety interests. Instead, restrictions must conform to historical tradition of regulating similar weapons.

But applying that framework to modern weapons and technologies creates problems. Automatic weapons didn’t exist during the Founding era. How do courts determine the historical analog for modern designs intended to facilitate conversion? Do they compare to historical regulations of “dangerous weapons generally”? To regulations of weapons that could be easily modified? To weapons that could fire many rounds rapidly?

Different analogies produce different outcomes. Broad historical tradition of regulating dangerous weapons might permit the ban. Narrow focus on historical treatment of specifically convertible weapons might not.

The Bruen framework assumes historical sources clearly address modern issues. But historical materials rarely speak directly to 21st-century weapon designs and conversion technologies. Courts must interpret historical principles and apply them to circumstances the Founders and 19th-century legislators never contemplated.

The “Common Use” Test Applied to Design Features

The NRA emphasizes that millions of Glocks exist in civilian hands – satisfying any reasonable “common use” test. But California would argue the relevant question isn’t whether the weapon is in common use, but whether the specific design feature enabling conversion to automatic fire is in common use.

Glock pistols are common. Cruciform trigger bars are common as internal components of Glocks. But conversion of semiautomatic pistols to automatic weapons is rare, illegal, and used primarily for criminal purposes. The NRA’s argument conflates the weapon’s general availability with the criminal utility of its specific design feature.

This distinction matters for the constitutional analysis. If “common use” means the weapon is widely possessed and used, Glocks qualify. If it means the weapon is commonly used for the protected purpose (lawful self-defense), Glocks also qualify since millions use them lawfully.

But if “common use” means the specific feature enabling automatic conversion is common among lawful users, California has a stronger case. Most Glock owners never convert their weapons and use standard semiautomatic functionality. The conversion feature, while technically present, remains legally unused by lawful owners.

The Federalism Question

California has long pushed boundaries on gun regulation. The state has implemented requirements like ammunition background checks, magazine capacity restrictions, assault weapons bans, and waiting periods – many of which have faced legal challenges.

Federal courts have struck down some California regulations as Second Amendment violations. But others have survived. The legal landscape remains contested and unstable as Bruen-era courts apply historical tradition analysis to modern weapon restrictions.

States traditionally held significant authority to regulate firearms within their borders. The Constitution’s Second Amendment applied only to federal government until 2010 when the Supreme Court incorporated it against states through the Fourteenth Amendment.

California sees gun regulation as legitimate state police power protecting public safety. The NRA sees such regulation as Second Amendment infringement. Where Bruen’s historical tradition analysis draws that line remains uncertain.

The Precedent This Case Sets

If courts uphold California’s ban, they signal that design features enabling weapon conversion can justify restrictions even on “in common use” weapons. States could ban other firearms based on design features they identify as enabling illegal conversion or modification.

If courts strike down the ban, they signal that state restrictions on weapons in common use face steep constitutional barriers even when justified by public safety concerns about criminal conversion or modification. The focus remains on the weapon’s lawful use capacity rather than criminal misuse risks.

Either way, the decision shapes Second Amendment jurisprudence in the post-Bruen era. Courts will establish how strictly the historical tradition test applies and how states can design regulations to survive constitutional challenge.

The Conversion Device Enforcement Problem

California’s strategy addresses a real law enforcement challenge: federal law prohibits conversion devices, but enforcement focuses on prosecuting people who already possess converted weapons. Preventing the crime upstream by restricting supply of easily convertible pistols could reduce illegal conversion incidents.

But the approach raises questions about preventing hypothetical crimes based on theoretical criminal capacity rather than actual criminal conduct. A Glock with a cruciform trigger bar commits no crime in standard use. The criminal risk emerges only if someone obtains a conversion device and illegally modifies the pistol.

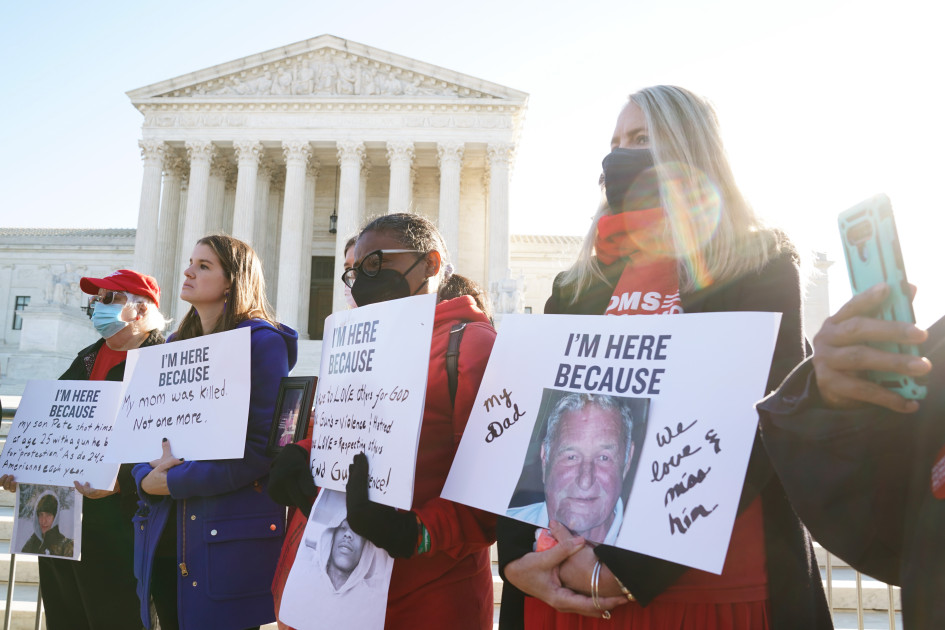

Gun rights advocates argue that restricting lawful weapons based on hypothetical criminal misuse violates Second Amendment principles. The focus should be on prosecuting actual conversion and use, not preventing civilians from possessing weapons that could theoretically be converted.

Law enforcement argues that reducing availability of easily convertible weapons prevents crime by making illegal conversion less practical. Fewer converted weapons mean fewer crimes committed with automatic fire capability.

The constitutional question is whether this preventive approach justifies restricting lawful commerce in weapons in common use. Can states restrict weapons based on criminal modification potential, or does such restriction violate the Second Amendment’s protection for in-common-use weapons?

What Happens Next

The lawsuit will proceed through federal district court and likely reach federal appeals court. The case will be decided under Bruen’s historical tradition framework, but courts will struggle to find historical sources addressing design features of semiautomatic weapons and conversion technology that didn’t exist historically.

Eventually, the Supreme Court may need to clarify how the historical tradition test applies to modern weapon designs and technologies. That clarification will establish boundaries for state weapons regulation in the post-Bruen era.

In the meantime, California’s ban takes effect July 1, 2026. Licensed firearms dealers cannot sell Glocks with cruciform trigger bars. The impact on civilian gun ownership remains modest since other semiautomatic pistols remain available. But the constitutional principle – whether design features enabling illegal conversion justify restricting lawful weapons – carries broader implications.

The NRA frames this as Second Amendment violation. California frames it as reasonable public safety regulation. The courts will decide which framing prevails under the Constitution’s text, history, and tradition – concepts that generate sharply different conclusions when applied to modern weapons technologies the Founders never contemplated.