U.S. District Judge William Young has been on the federal bench for nearly 40 years. He’s a Reagan appointee with impeccable conservative credentials. And in 2025, he’s become something extraordinary in American jurisprudence: a sitting federal judge who writes legal opinions that read more like constitutional manifestos, complete with historical references, Reagan quotes, and direct challenges to the President’s understanding of American government.

His latest 161-page opinion blocking Trump’s deportation of pro-Palestinian protesters is just the most recent salvo in what’s become an unusual judicial campaign. But there’s a twist that makes this constitutionally complicated: the Supreme Court already slapped Young down once this year for ignoring their emergency guidance. So when does vigorous judicial independence cross the line into judicial activism?

At a Glance

- Judge William Young, appointed by Reagan in 1985, has issued multiple scathing opinions against Trump administration policies

- The Supreme Court rebuked Young in August for failing to follow the Court’s emergency ruling on education grant cuts

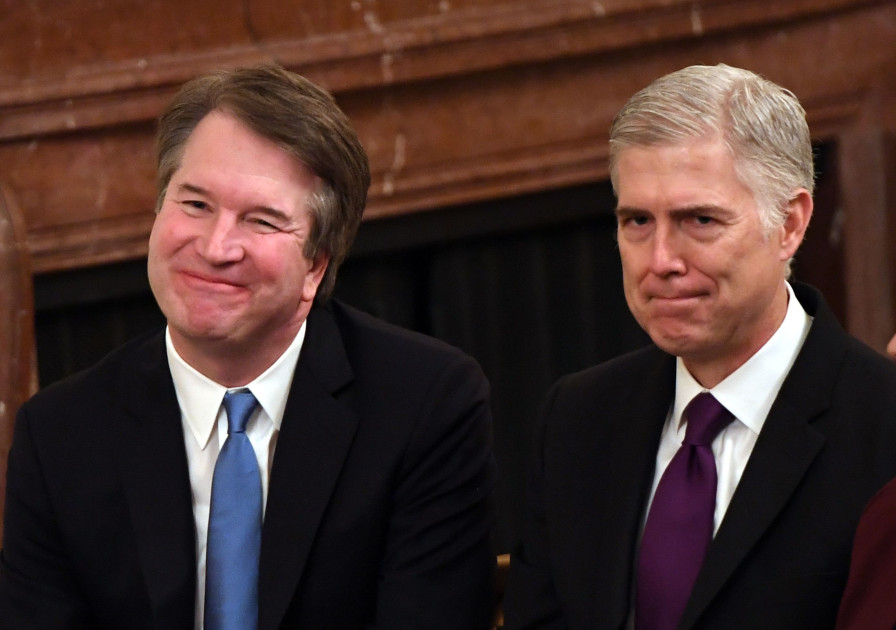

- Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh warned that “when this Court issues a decision, it constitutes a precedent that commands respect in lower courts”

- Young apologized for the error but continues issuing opinions that criticize Trump’s “hollow bragging” and “retribution”

- At stake: the constitutional boundary between judicial independence and judicial defiance of higher courts

The Judge Who Writes Like a Founding Father

Young’s opinions this year have been remarkable not just for their conclusions but for their tone. In June, he blocked Trump’s cuts to National Institutes of Health research grants, calling them “appalling” evidence of “racial discrimination” and “discrimination against the LGBTQ community.” He added: “I have never seen government racial discrimination like this in my decades on the federal bench. I would be blind not to call it out. Have we no shame?”

That’s not typical judicial language. Federal judges usually write in measured, technical prose, carefully avoiding inflammatory rhetoric even when ruling against the government. Young has abandoned that convention entirely.

His Tuesday opinion on the pro-Palestinian deportation case is even more striking. Across 161 pages, Young doesn’t just rule that Trump violated the First Amendment – he accuses the President of being a “bully” who “ignores everything” from the Constitution to civil laws, focused on “hollow bragging” and “retribution” while fundamentally misunderstanding the country he was elected to serve.

“I fear President Trump believes the American people are so divided that today they will not stand up, fight for, and defend our most precious constitutional values so long as they are lulled into thinking their own personal interests are not affected. Is he correct?” – Judge William Young

That rhetorical question – posed directly in an official judicial opinion – is extraordinary. Young isn’t just deciding a case. He’s issuing a civic alarm, using his judicial platform to warn about threats to constitutional democracy.

The Supreme Court Slap-Down

Here’s where Young’s crusade gets constitutionally problematic: he’s not just challenging Trump. He’s already defied the Supreme Court once this year.

The NIH grants case that Young blocked in June eventually reached the Supreme Court on emergency appeal. The Trump administration argued that Young had ignored precedent set in an April Supreme Court decision that allowed the President to slash education grants for diversity, equity, and inclusion programs.

In August, the Supreme Court voted 5-4 to lift Young’s injunction. But Justices Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh went further, using their opinion to directly criticize Young’s approach. They wrote: “When this Court issues a decision, it constitutes a precedent that commands respect in lower courts.”

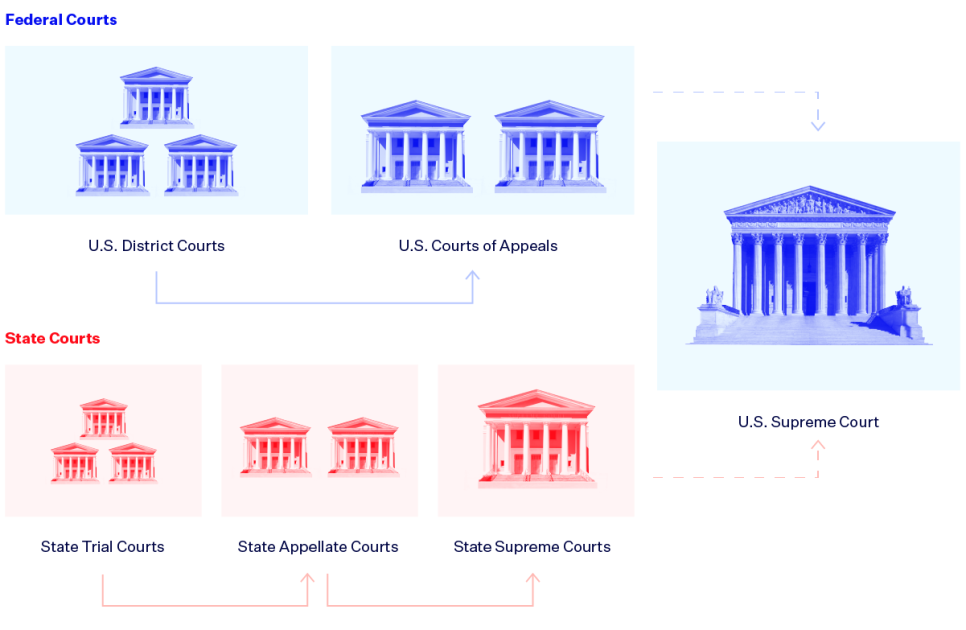

That’s judicial language for “you ignored us, and that’s not okay.” The Supreme Court sits atop the federal judicial hierarchy. When it issues guidance – even in emergency rulings – lower courts are supposed to follow it. Young didn’t. He distinguished the cases, found the Trump administration’s actions unconstitutional anyway, and wrote an opinion that treated the Supreme Court’s emergency ruling as irrelevant to his analysis.

Federal judges have life tenure precisely so they can rule without fear of political retaliation. But that independence assumes they’ll still operate within the judicial hierarchy where the Supreme Court’s word is final.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, writing in dissent, seemed sympathetic to Young’s frustration with what she called the Court’s inconsistent emergency docket. She quipped: “Calvinball has only one rule: There are no fixed rules. We seem to have two: that one, and this administration always wins.”

Young apologized for the error. But his Tuesday opinion suggests the apology didn’t change his broader approach to these cases.

The Constitutional Tightrope of Judicial Independence

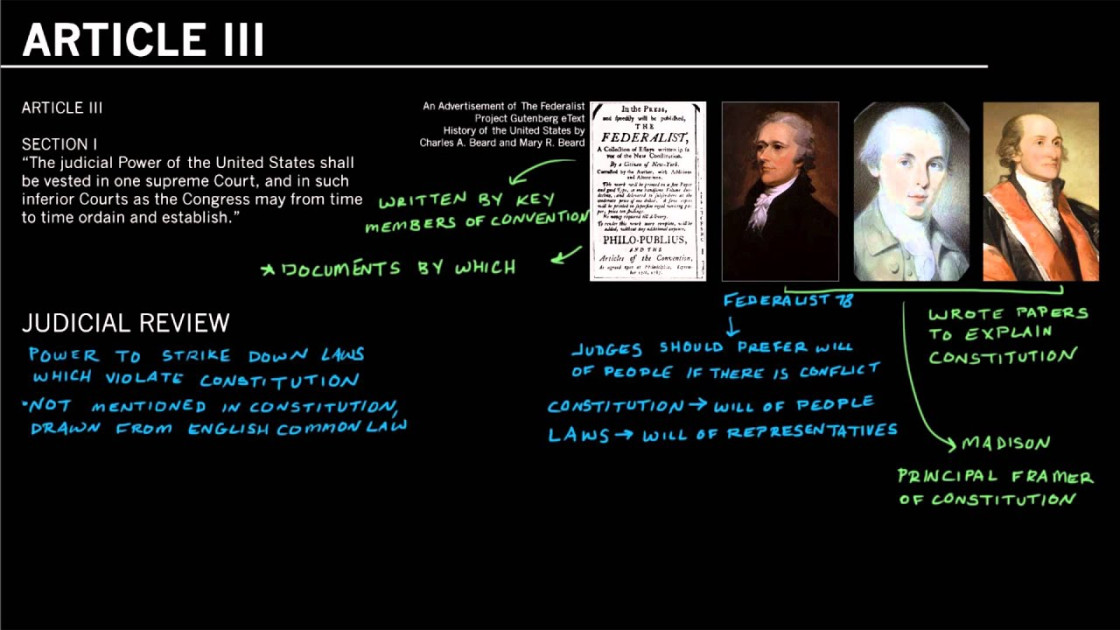

Article III of the Constitution gives federal judges life tenure “during good Behaviour.” The Framers did this deliberately – they wanted judges insulated from political pressure, free to rule on the law without worrying about reelection or reappointment.

That independence is essential to the separation of powers. Congress makes the laws, the President executes them, and judges interpret them. If judges can be fired or intimidated by the political branches, the whole system collapses. The judiciary loses its ability to check executive and legislative power.

But judicial independence has limits. Federal judges aren’t philosopher-kings who can rule however they want. They’re bound by the Constitution, statutes passed by Congress, and precedents set by higher courts. A district judge like Young is at the bottom of the federal judicial hierarchy. Above him sits the First Circuit Court of Appeals, and above that, the Supreme Court.

When Young ignores Supreme Court guidance – even emergency guidance – he’s claiming an independence that goes beyond what Article III provides. He’s essentially saying his interpretation of the Constitution matters more than the Supreme Court’s, at least until they formally reverse him on appeal.

That’s a dangerous position for any district judge to take, no matter how well-intentioned.

When Judicial Independence Becomes Resistance

There’s a term that’s been floating around legal circles to describe what Young is doing: judicial resistance. It’s the idea that judges opposed to Trump’s policies should use every tool at their disposal – broad readings of statutes, aggressive use of preliminary injunctions, expansive rhetoric in opinions – to slow down or block the administration’s agenda.

Some legal scholars on the left have openly advocated for this approach, arguing that Trump’s policies are so dangerous to constitutional democracy that judges have a duty to resist. Others, including many liberal judges and legal academics, have pushed back hard, arguing that judges who become partisan actors undermine the legitimacy of the entire judicial system.

Young’s opinions this year walk right up to that line – and arguably cross it. When he writes that Trump “ignores everything” and is focused on “hollow bragging” and “retribution,” he’s not engaging in dispassionate legal analysis. He’s making political and moral judgments about the President’s character and fitness for office.

“Yet government retribution for speech (precisely what has happened here) is directly forbidden by the First Amendment.” – Judge William Young

That doesn’t mean his legal conclusions are wrong. Young might be absolutely correct that Trump’s deportation efforts violated the First Amendment and that the NIH grant cuts were discriminatory. But the way he’s expressing those conclusions – the rhetoric, the moralizing, the direct attacks on the President’s motives and character – goes beyond what we typically expect from judicial opinions.

The Reagan Connection

There’s deep irony in Young’s approach. He was appointed by Ronald Reagan in 1985, during an era when Republicans were intensely focused on appointing judges who would practice “judicial restraint” – deciding cases narrowly based on the law and facts, without injecting personal views or making broad policy pronouncements.

Reagan himself gave famous speeches about freedom and constitutional values – speeches that Young now quotes in his opinions to criticize a Republican president. In his Tuesday ruling, Young invoked Reagan’s words: “Freedom is a fragile thing and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction.”

Young is using his Reagan pedigree as moral authority for his resistance to Trump. He’s essentially arguing that Reagan’s vision of American freedom and constitutional government is being betrayed by the modern Republican Party, and he – a Reagan appointee – has a duty to say so from the bench.

That’s a powerful rhetorical move. It also raises questions about whether judges should be invoking the political philosophies of the presidents who appointed them to justify their rulings. If Judge Young can cite Reagan to oppose Trump, can Trump-appointed judges cite Trump to support expansive executive power?

What the Founders Would Say

Hamilton argued in Federalist 78 that the judiciary would be “the least dangerous branch” because it has “neither FORCE nor WILL but merely judgment.” Judges don’t command armies or control budgets – they just interpret laws. Their power comes entirely from the legitimacy and respect their judgments command.

When judges start sounding like political activists rather than neutral arbiters, they risk undermining that legitimacy. Even if Young is substantively correct in his rulings, the rhetorical flourishes and personal attacks on Trump make his opinions look partisan rather than judicious.

Madison would likely worry that Young is concentrating too much power in his own hands by ignoring Supreme Court guidance. The whole point of the judicial hierarchy is to prevent individual judges from becoming mini-tyrants who impose their personal visions of constitutional law regardless of what higher courts say.

Jefferson, who had his own battles with the federal judiciary, would probably see this as evidence that life tenure for judges creates unaccountable power. But even Jefferson accepted that courts had a role in checking executive excess – he just wanted the political branches to have more control over who served as judges.

The Precedent Problem

Here’s the long-term danger in what Young is doing: if liberal judges can ignore conservative Supreme Court guidance they disagree with, what’s to stop conservative judges from ignoring liberal Supreme Court precedents?

We’ve already seen hints of this during the Obama and Biden administrations, when conservative district judges in Texas issued nationwide injunctions blocking immigration and healthcare policies they disagreed with, often using aggressive rhetoric about executive overreach.

If judicial independence means every district judge gets to be a constitutional supreme court unto themselves – issuing sweeping injunctions based on their personal reading of the Constitution regardless of higher court guidance – then we don’t really have a judicial hierarchy anymore. We have 600-plus district judges each acting as a potential veto point on any federal policy.

The Constitution created one Supreme Court precisely to ensure uniformity in federal law. When district judges start ignoring that Court’s guidance, the whole system breaks down.

That might sound good if you agree with Judge Young’s specific rulings. It’s a nightmare for the rule of law in the long term.

The Line Between Independence and Defiance

There’s a real constitutional question here that goes beyond politics: where’s the line between appropriate judicial independence and inappropriate judicial defiance?

Judges should be independent enough to rule against the government when the law requires it, even when that’s politically unpopular. They should be free to write opinions explaining their reasoning thoroughly, even when that reasoning criticizes executive branch actions.

But judges shouldn’t ignore Supreme Court precedents they personally disagree with. They shouldn’t use their opinions as platforms for broad political commentary unrelated to the specific legal questions before them. And they shouldn’t treat their judicial role as an opportunity to become thought leaders in political resistance movements.

Young’s opinions this year – particularly after the Supreme Court rebuke in August – suggest he’s crossed that line. He’s not just being an independent judge. He’s being a defiant judge who views his role as speaking truth to power regardless of what higher courts say.

That’s constitutionally problematic even when his substantive rulings might be correct on the merits.

The Constitutional Stakes

Young’s approach creates a legitimacy crisis for the federal judiciary. When judges start looking like partisan actors – whether liberal judges blocking Trump or conservative judges who blocked Obama and Biden – public confidence in the courts declines. People stop seeing judges as neutral arbiters applying the law and start seeing them as just another set of political players wearing robes.

That’s dangerous because the judiciary’s power depends entirely on public acceptance of its legitimacy. Courts can’t enforce their own orders – they depend on the executive branch to do that. If presidents and the public conclude that judges are just political opponents with gavels, the whole system of judicial review becomes unstable.

Young clearly believes Trump poses such a serious threat to constitutional norms that extraordinary judicial pushback is necessary. He’s using his platform to sound an alarm about what he sees as creeping authoritarianism. But in doing so, he’s contributing to the erosion of judicial norms that might ultimately make it easier for future presidents – Trump or anyone else – to ignore court orders they disagree with.

The Constitution gave judges independence so they could check political power. But it also created a judicial hierarchy so individual judges couldn’t become political actors themselves. Young is testing the limits of both principles – and the Supreme Court has already warned him once that he’s gone too far.

Whether he’ll moderate his approach or continue his crusade, we’re about to find out. But the broader question remains: in our constitutional system, who checks the checkers when judges stop following the rules?