A Baptist church in Middleton, Idaho was renting a gymnasium from a public charter school to hold Sunday services. Then the school applied for $15 million in state bonds to finance building upgrades, and state attorneys flagged the church’s lease as a potential constitutional problem under Idaho’s 19th-century restriction on giving taxpayer money to religious organizations.

The lease got canceled. The church sued. And Chief U.S. District Court Judge David Nye just ruled that Idaho violated the First Amendment by treating a religious organization differently than it would treat any secular group renting the same space.

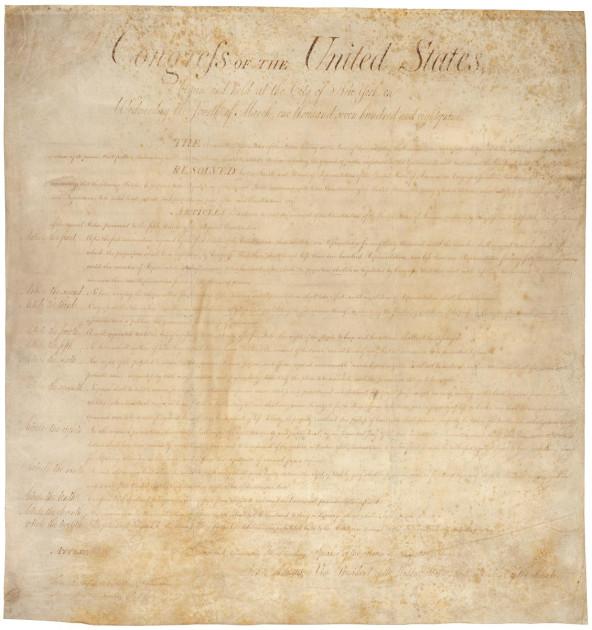

The Blaine Amendment That Created This Mess

Idaho’s constitution contains what’s called a Blaine Amendment – a provision that blocks religious organizations from receiving taxpayer money. These amendments exist in roughly three dozen state constitutions, and they have a troubling history that’s rarely discussed in modern legal disputes.

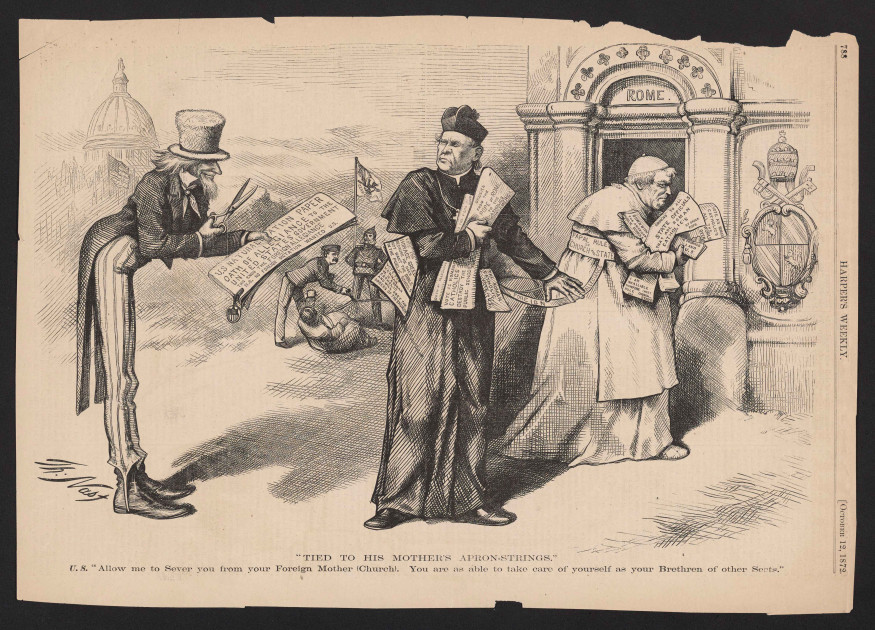

Blaine Amendments emerged in the 1870s during a wave of anti-Catholic sentiment driven by Protestant fears about Catholic immigration. James G. Blaine, a Republican congressman from Maine, proposed a federal constitutional amendment prohibiting public funds from going to “sectarian” schools – code for Catholic schools at a time when public schools routinely included Protestant Bible readings and prayers.

The federal amendment failed, but states adopted similar provisions in their own constitutions. The language targeted “sectarian” institutions while protecting the Protestant character of public education. They were discriminatory by design, meant to exclude Catholic institutions from public funding while maintaining Protestant religious influence in public schools.

Modern courts have struggled with how to apply these 19th-century religious discrimination provisions in contemporary First Amendment cases. Some view Blaine Amendments as neutral restrictions on government funding of religion. Others recognize them as products of religious bigotry that shouldn’t be used to justify discrimination against religious organizations today.

Judge Nye’s ruling suggests Idaho’s bonding authority fell into the trap of using a historically discriminatory provision to justify treating a religious organization worse than a secular one – which is exactly what the First Amendment prohibits.

What the Idaho Housing and Finance Association Got Wrong

When Sage International charter school applied for bonds through the Idaho Housing and Finance Association (IHFA), attorneys for the state bonding authority flagged Truth Family Bible Church’s lease as potentially violating Idaho’s Blaine Amendment. Their concern was that if bond money financed building upgrades to the gymnasium, the church would indirectly benefit from taxpayer funds.

That analysis sounds superficially reasonable until you examine what it actually means. The church was paying rent to use the gym on Sundays. Bond money would finance upgrades to school facilities that the school uses for educational purposes Monday through Saturday. The church would benefit from improved facilities only to the extent that any tenant benefits when a landlord makes improvements to leased property.

Judge Nye called the bonding authority’s concern a “lapse in judgment,” writing that Truth Family Bible Church would have “only incidentally benefited from the bond-improved facilities,” with no funds being given directly to them. The church was a paying tenant, not a subsidy recipient.

The bonding authority’s logic would mean that any religious organization renting space from an entity that receives any government funding creates a constitutional violation. Churches couldn’t rent public school gyms. Religious nonprofits couldn’t lease space in buildings with federal historic preservation grants. Synagogues couldn’t rent convention centers owned by cities.

That’s not how the First Amendment works. Government neutrality toward religion doesn’t require treating religious organizations as radioactive contaminants that can’t come into contact with anything touched by public funds. It requires treating them the same as comparable secular organizations.

A secular nonprofit renting the same gym wouldn’t have triggered Blaine Amendment concerns. The only reason Truth Family Bible Church’s lease became problematic was because it’s a church – which is textbook religious discrimination.

The Three First Amendment Violations Nobody Expected

The church’s attorney argued that using Idaho’s Blaine Amendment to terminate the lease violated three separate First Amendment provisions: the Free Exercise Clause, the Establishment Clause, and the Free Speech Clause. Judge Nye agreed with all three arguments.

The Free Exercise violation is straightforward. The government can’t burden religious practice without compelling justification. Canceling a church’s lease specifically because it’s a church – when secular organizations could maintain identical leases without problem – burdens that church’s religious practice based solely on its religious identity.

The Establishment Clause violation is more subtle. The Establishment Clause prohibits government from favoring or disfavoring religion. By treating religious organizations worse than secular ones in lease arrangements, Idaho wasn’t maintaining neutrality – it was actively discriminating against religion. That violates the Establishment Clause just as much as favoring religion would.

The Free Speech violation addresses how the lease cancellation “effectively stifled” the church’s religious speech, according to Judge Nye’s ruling. The gymnasium provided a venue where the church could gather and conduct services. Terminating that venue specifically because the speech happening there was religious in nature constitutes viewpoint discrimination – the government punishing speech based on its content or perspective.

All three violations stemmed from the same fundamental error: treating a religious organization differently than a secular one would be treated in identical circumstances.

What Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador Understood

Idaho Attorney General Raúl Labrador’s office intervened in the case on the church’s side, arguing that government agencies can’t discriminate against religious organizations simply because they’re religious. After Nye’s ruling, Labrador said through a spokesperson: “Truth Family Bible Church deserved the same treatment as any secular group, and we’re glad the court recognized this.”

That framing is significant because it shifts focus from whether religious organizations should receive government benefits to whether they should be excluded from generally available opportunities. The church wasn’t asking for special accommodation or preferential treatment – it was asking to be treated the same as any other organization renting gymnasium space.

The distinction matters for how we understand religious freedom in practice. Some view religious liberty as demanding exemptions and special treatment that allow religious organizations to operate under different rules. Others view it as demanding equal treatment that prevents government from singling out religious organizations for either favoritism or discrimination.

Labrador’s position reflects the latter understanding. Religious organizations shouldn’t get special subsidies, but they also shouldn’t be excluded from neutral programs or treated worse than secular organizations accessing the same opportunities.

That principle has broad implications beyond church gym leases. It affects religious schools’ ability to participate in generally available education programs, religious nonprofits’ eligibility for government grants available to secular nonprofits, and religious organizations’ access to public facilities available to other community groups.

The Supreme Court has been moving in this direction for years, consistently ruling that excluding religious organizations from generally available programs constitutes discrimination rather than constitutional neutrality. Judge Nye’s ruling applies that principle to Idaho’s Blaine Amendment in ways that limit how the state can use that provision to justify treating religious organizations differently.

The IHFA Response That Sounds Like Relief

After the ruling, an Idaho Housing and Finance Association spokesperson told Idaho Education News: “We welcome the legal clarity the court’s ruling provides, helping to ensure that this type of issue doesn’t arise in the future.”

That’s a diplomatic way of saying the bonding authority is happy to have clear guidance that prevents them from making the same mistake again. IHFA didn’t want to discriminate against the church – they were trying to comply with what they understood Idaho’s constitution to require.

The problem was that Idaho’s Blaine Amendment, interpreted the way IHFA’s attorneys suggested, would create perpetual First Amendment violations by requiring religious discrimination. The federal Constitution supersedes state constitutional provisions when they conflict, so any interpretation of Idaho’s Blaine Amendment that requires First Amendment violations is invalid.

Judge Nye’s ruling doesn’t strike down Idaho’s Blaine Amendment, but it constrains how the state can apply it. Idaho can refuse to directly fund religious organizations or religious activities. It can’t use the Blaine Amendment to exclude religious organizations from neutral opportunities available to comparable secular groups.

That distinction allows Idaho to maintain its constitutional provision while ensuring it doesn’t conflict with federal constitutional requirements. IHFA now has clear guidance that a paying tenant’s religious identity doesn’t create Blaine Amendment problems just because the landlord receives bond financing for facility improvements.

What Truth Family Bible Church Actually Is

Truth Family Bible Church describes itself on its website as “a new church plant in Middleton, Idaho” that began as a home Bible study that grew large enough to need its own congregation. “Our goal is to faithfully minister the Word of God as a light to our community and the world, declaring that Christ is Lord of all,” the church states.

This isn’t a megachurch with vast resources and political connections. It’s a small Baptist congregation that started in someone’s living room and eventually needed to rent space to accommodate growing attendance. They found a charter school willing to lease them a gymnasium for Sunday services when the school wasn’t using it.

The arrangement benefited everyone. The church got affordable space for services. The school got rental income. Students and church members never overlapped because services happened on Sundays when school wasn’t in session. It was exactly the kind of mutually beneficial community partnership that public facilities often enable.

Then state attorneys flagged it as a constitutional problem, and the church lost its meeting space. Now the congregation holds Sunday services at another school’s gym – presumably one that isn’t applying for state bond financing that might trigger similar Blaine Amendment concerns.

The ruling means Truth Family Bible Church can potentially return to its original venue at Sage International, though whether the school chooses to reinstate the lease after this controversy is unclear. The legal precedent protects other religious organizations from facing similar discrimination, which matters more than any individual lease arrangement.

The Historical Pattern That Keeps Repeating

Cases like this expose the tension between 19th-century anti-Catholic discrimination codified in state constitutions and modern First Amendment doctrine that prohibits treating religious organizations worse than secular ones. Blaine Amendments were designed to exclude Catholic institutions while maintaining Protestant influence in public life.

Modern courts applying those provisions must decide whether to enforce their original discriminatory purpose or reinterpret them consistent with contemporary constitutional requirements. Judge Nye chose the latter approach, ruling that whatever Idaho’s Blaine Amendment might mean, it can’t be used to justify treating churches worse than secular organizations in equivalent circumstances.

This pattern has played out across the country as religious organizations challenge Blaine Amendment-based discrimination. Montana’s Supreme Court ruled that excluding religious schools from a scholarship program violated equal treatment principles. Maine faced similar litigation over excluding religious schools from tuition assistance programs.

In each case, the question is whether state constitutional provisions rooted in religious bigotry can justify modern discrimination against religious organizations. Federal courts have consistently said no – states can maintain Blaine Amendments, but they can’t use them to treat religious organizations worse than secular ones accessing neutral government programs or opportunities.

That principle protects religious liberty while respecting legitimate concerns about government funding of religion. Direct subsidies for religious activities remain prohibited. But religious organizations can’t be excluded from generally available opportunities just because they’re religious.

Why Small Cases Like This Matter More Than Headline Decisions

Truth Family Bible Church v. Sage International won’t generate Supreme Court analysis or law school casebook inclusion. It’s a district court decision about a church gym lease in Idaho. But it matters because it demonstrates how constitutional principles operate in ordinary circumstances affecting regular people.

This wasn’t about high-profile national controversies or politically charged religious freedom debates. It was about a small congregation that needed somewhere to hold Sunday services and found a school willing to rent them space. Then state attorneys, trying to ensure constitutional compliance, created a constitutional violation by treating the church differently than they would treat a secular tenant.

Judge Nye’s ruling protects future religious organizations from facing similar discrimination. It clarifies that Idaho’s Blaine Amendment can’t be used to justify excluding churches from neutral lease arrangements. It ensures that religious organizations receive equal treatment rather than special exclusion.

Those protections matter most for small congregations like Truth Family Bible Church that lack resources to fight extended legal battles. Megachurches can afford attorneys and alternative venues. Church plants meeting in rented gymnasiums can’t.

The ruling means the next small religious organization facing similar discrimination will have clear legal precedent supporting equal treatment. State agencies will know they can’t use Blaine Amendments to exclude religious tenants from lease arrangements available to secular organizations. And religious communities will have one less barrier to finding affordable meeting space.

That’s not dramatic constitutional revolution. It’s incremental protection of religious freedom through ordinary legal processes resolving specific disputes. But incremental protection builds the foundation that makes religious liberty real rather than theoretical for the small congregations that need it most.

Truth Family Bible Church just wanted to rent a gym for Sunday services. Idaho’s bonding authority thought the state constitution prohibited it. A federal judge ruled the U.S. Constitution requires treating churches the same as any other organization.

Now the congregation has legal clarity, Idaho has guidance for future cases, and religious freedom in America is slightly more secure than it was before one small church decided to sue rather than accept discrimination.