The Supreme Court has punted. In a major Louisiana redistricting case that could redefine the rules for drawing congressional maps, the justices have declined to issue a ruling, instead ordering new arguments for their next term. This is not a simple delay; it is a sign of the Court’s deep struggle with a seemingly unsolvable constitutional puzzle that is fueling political chaos across the country.

This case, and the simultaneous political meltdown in Texas where Democratic lawmakers have fled the state to block a new map, exposes the impossible tightrope that states are now forced to walk. Under our current legal framework, states can be sued for considering race too little in the redistricting process, and then immediately sued for considering it too much. This legal paradox has become the central, high-stakes battlefield in the war for political power in America.

A Constitutional Catch-22 in Louisiana

The case of Louisiana v. Callais is a perfect illustration of this constitutional Catch-22.

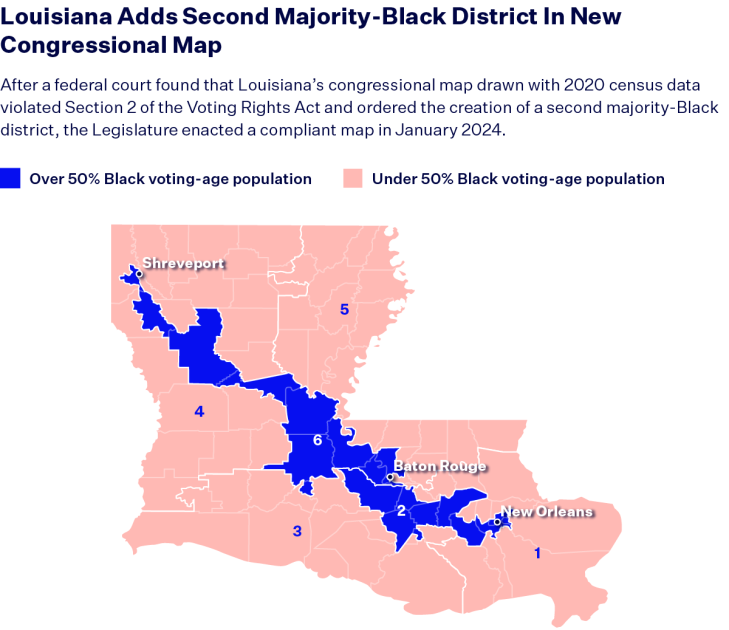

First, after the 2020 census, Louisiana’s Republican-led legislature drew a congressional map with only one majority-Black district out of six, despite the state’s population being nearly one-third Black. A federal court struck this map down, ruling that it likely violated the Voting Rights Act of 1965 by illegally diluting the power of Black voters.

Forced back to the drawing board, the legislature then created a new map with a second, “sinuous and jagged” majority-Black district. This new map was immediately challenged in court by a different group of plaintiffs, who argued that in order to create this district, the legislature had made race the “predominant” factor, thus creating an unconstitutional racial gerrymander in violation of the 14th Amendment.

Two Competing Constitutional Commands

This leaves states caught between two powerful, and seemingly contradictory, legal mandates.

On one hand, Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act requires that minority voters have an equal opportunity to participate in the political process and elect candidates of their choice. This has been interpreted by courts to mean that states must create majority-minority districts where it is possible to do so.

On the other hand, the Supreme Court has ruled in cases like Shaw v. Reno (1993) that the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment forbids making race the overriding, predominant factor in drawing district lines. The Court has warned that such a process is dangerously close to the very racial segregation the Constitution is meant to prohibit.

How can a state legislature possibly draw a majority-minority district as required by the Voting Rights Act without race being the “predominant factor” as prohibited by the 14th Amendment? This is the constitutional tightrope the Supreme Court is now struggling to define.

When Law Fails, Politics Takes Over

The dramatic events in Texas are a direct symptom of what happens when this legal framework becomes a deadlock. Frustrated by a proposed Republican map they see as an aggressive gerrymander, Democratic state legislators have fled the state entirely. By denying the legislative body a quorum, they have used a raw political power play to grind the process to a halt.

This kind of radical, hardball tactic is a sign of a broken constitutional process. When the legal rules are so convoluted and contradictory that they lead to endless litigation with no clear answers, the political parties will abandon the legal process and resort to sheer force to achieve their goals. As New York’s governor declared while welcoming the Texas Democrats, “We are at war.”

The Supreme Court’s decision to delay its ruling in the Louisiana case is a reflection of the profound difficulty of the issue. But in the meantime, redistricting has become the primary battlefield in the American political war. The current constitutional framework has created a paradox with no easy answer, leading to endless lawsuits and political chaos. This is about more than just a few congressional seats; it is a test of whether our constitutional system is still capable of producing a fair and trusted process for representative democracy.