In a stunning legal maneuver, the Internal Revenue Service has fundamentally altered a 70-year-old rule that has long served as a wall between tax-exempt churches and partisan politics.

In a joint court filing with the very religious groups that were suing it, the IRS has agreed that the law prohibiting political campaign intervention does not apply to what is said from the pulpit to the pews.

This is not a minor regulatory tweak. It is a seismic shift that redefines the relationship between faith and politics in America. The move, celebrated by religious conservatives as a victory for free speech, is being condemned by critics as a decision that could turn houses of worship into unregulated, tax-exempt arms of political campaigns.

The Lawsuit and the Surprising Agreement

The story began with a lawsuit filed last year by several religious organizations, including National Religious Broadcasters, against the IRS. They challenged the constitutionality of a law known as the Johnson Amendment.

But instead of fighting the lawsuit in court, the IRS effectively surrendered.

In a joint filing, the tax agency agreed with the churches that the law should not be enforced against “bona fide communications internal to a house of worship, between the house of worship and its congregation, in connection with religious services.”

Essentially, the IRS has agreed that a pastor or other religious leader can discuss and even endorse political candidates from the pulpit during a religious service without fear of losing their church’s precious tax-exempt status.

What is the Johnson Amendment?

To understand the magnitude of this change, one has to understand the rule that has governed churches and non-profits for generations.

The Johnson Amendment is a 1954 provision in the U.S. tax code, championed by then-Senator Lyndon B. Johnson. It explicitly forbids all 501(c)(3) non-profit organizations – which includes charities, educational institutions, and houses of worship – from participating in or intervening in “any political campaign on behalf of (or in opposition to) any candidate for public office.”

“For 70 years, the Johnson Amendment has served as a truce line, allowing religious groups to speak on political issues, but not to endorse or oppose specific candidates.”

The penalty for violating this rule is severe: the loss of tax-exempt status, meaning the organization would have to pay taxes and donations to it would no longer be tax-deductible. While the IRS has rarely enforced this provision against churches, its mere existence has had a powerful “chilling effect” on political speech from the pulpit.

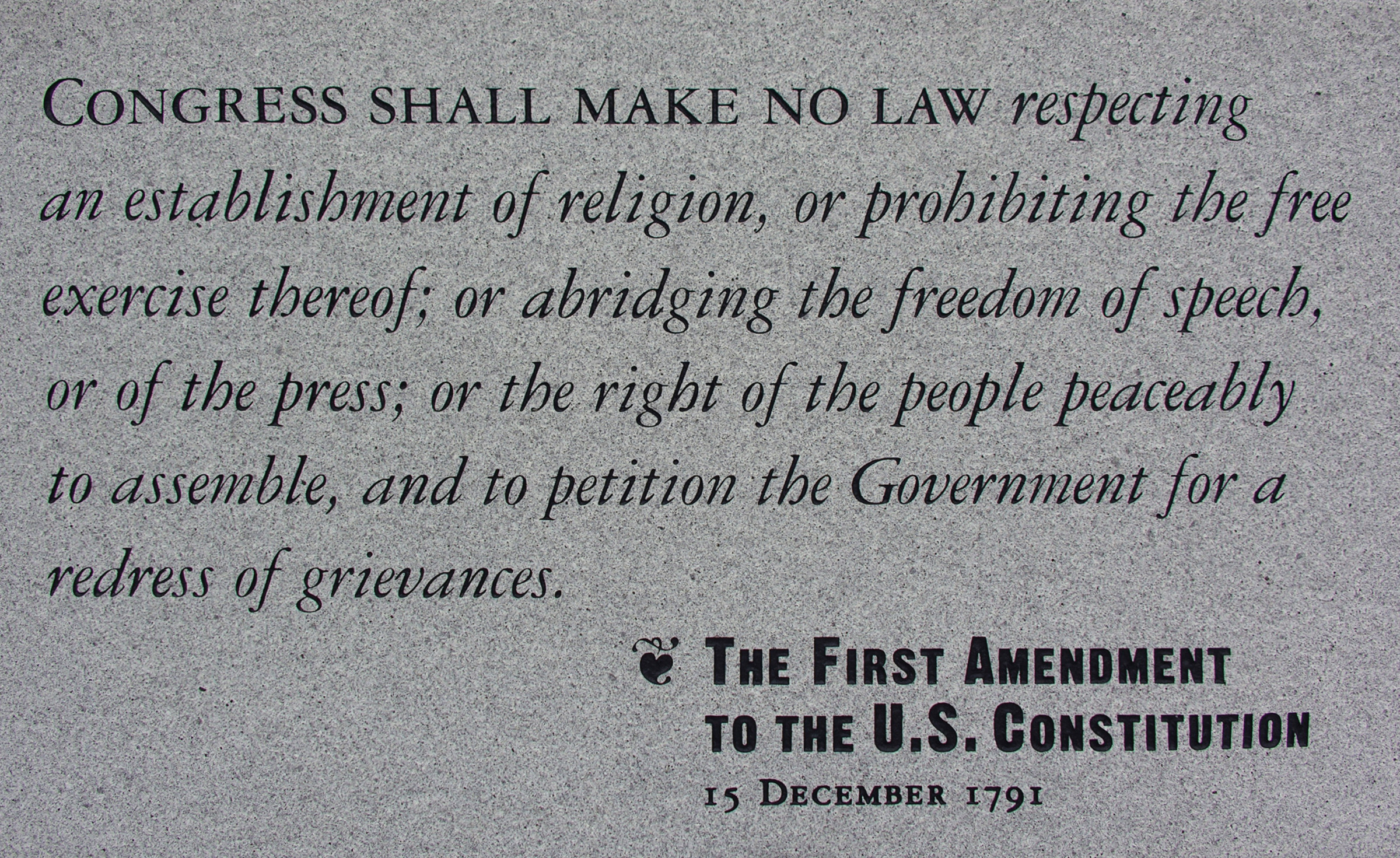

A First Amendment Collision

This entire debate is a classic constitutional collision, pitting different clauses of the First Amendment against each other.

Religious leaders and conservative groups have long argued that the Johnson Amendment is an unconstitutional violation of their rights to Free Speech and the Free Exercise of religion. They ask: How can the government tell a pastor what he or she can or cannot say when speaking to their own congregation about moral issues, especially when those issues intersect with politics?

On the other side are proponents of a strict separation of church and state. They argue that allowing churches to engage in partisan politics violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the government from making any law “respecting an establishment of religion.”

“The central fear is that this will transform churches into unregulated, tax-deductible Super PACs, where political donations can be laundered through the collection plate.”

They argue that tax-exempt status is a form of government subsidy. Allowing that subsidy to flow to organizations that are actively engaged in electioneering, they contend, is a dangerous entanglement of government and religion.

The New Political Landscape

This new IRS stance, which will now be enforced as part of a court-ordered injunction, dramatically changes the political landscape.

It empowers a specific, and often highly organized, segment of the electorate. Pastors and religious leaders in politically active congregations now have a federal green light to mobilize their flocks for or against specific candidates during their services.

This could have a profound impact on elections, particularly in deeply religious communities. It allows for a level of direct, trusted political communication that secular campaigns can only dream of.

A New Era for Pulpit and Politics

While this change is being hailed as a victory for religious freedom by its supporters, it comes with significant risks for the very institutions it seeks to empower.

By inviting overt partisan politics into the sanctuary, this new interpretation threatens to politicize houses of worship in an unprecedented way. It could introduce the same bitter divisions that have fractured the nation’s secular politics directly into congregations, pitting member against member.

The wall erected by the Johnson Amendment, however flawed, was designed not just to protect the state from the church, but also to protect the church from the corrupting influence of partisan politics. With that wall now significantly lowered, a new and uncertain era for both faith and politics in America has begun.