What if your job in government depended not on competence, but on loyalty to the president?

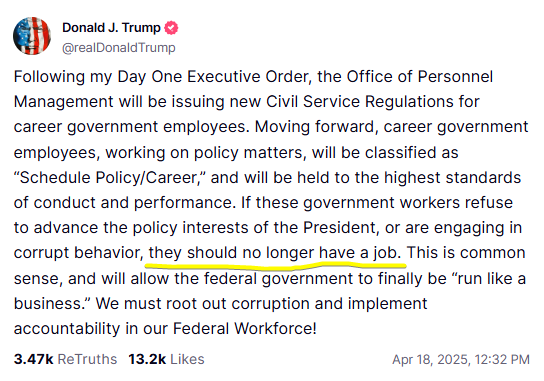

That’s the question at the heart of a sweeping proposal unveiled this week, in which the Trump campaign pledged to implement a new civil service classification—“Schedule Policy/Career”—for federal employees who work on policy. Under this reclassification, government workers who “refuse to advance the policy interests of the President” could be dismissed from their roles.

Described by supporters as a common-sense push for accountability, the plan amounts to a dramatic reshaping of the federal workforce. But beneath the buzzwords and bravado lies a far more serious constitutional concern: a presidency that treats neutral civil servants as political loyalists not only shreds historical precedent—it undermines the very structure of American governance.

The New Classification: Schedule Policy/Career

According to the proposal, the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) would issue new civil service regulations on “Day One” of a new Trump administration. These rules would carve out a new employment category for career federal employees whose work touches on policy. Unlike traditional civil servants, these employees could be removed for failing to align with the president’s agenda.

On its face, the plan is framed as a crackdown on corruption and bureaucracy. In practice, it would likely give the White House unprecedented power to dismiss long-serving federal employees across dozens of agencies—regardless of professional expertise or statutory protections.

Supporters call it “running government like a business.” But the federal government isn’t a business—and the Constitution was never meant to allow one person to staff it like a personal firm.

A Constitutional Balancing Act—or a Power Grab?

The most immediate constitutional concern is separation of powers. The federal civil service exists to implement laws passed by Congress, not to push the ideological goals of any one administration. Civil servants are trained professionals—economists, scientists, intelligence analysts, foreign service officers—tasked with carrying out lawful programs under neutral standards.

If these workers can be dismissed for refusing to “advance the president’s policy,” that flips the structure upside down. Suddenly, the executive is no longer faithfully executing the law—it’s remaking the workforce in its own image.

And that’s where the constitutional tension sharpens. The president does not get to govern by loyalty test.

Due Process Under Siege

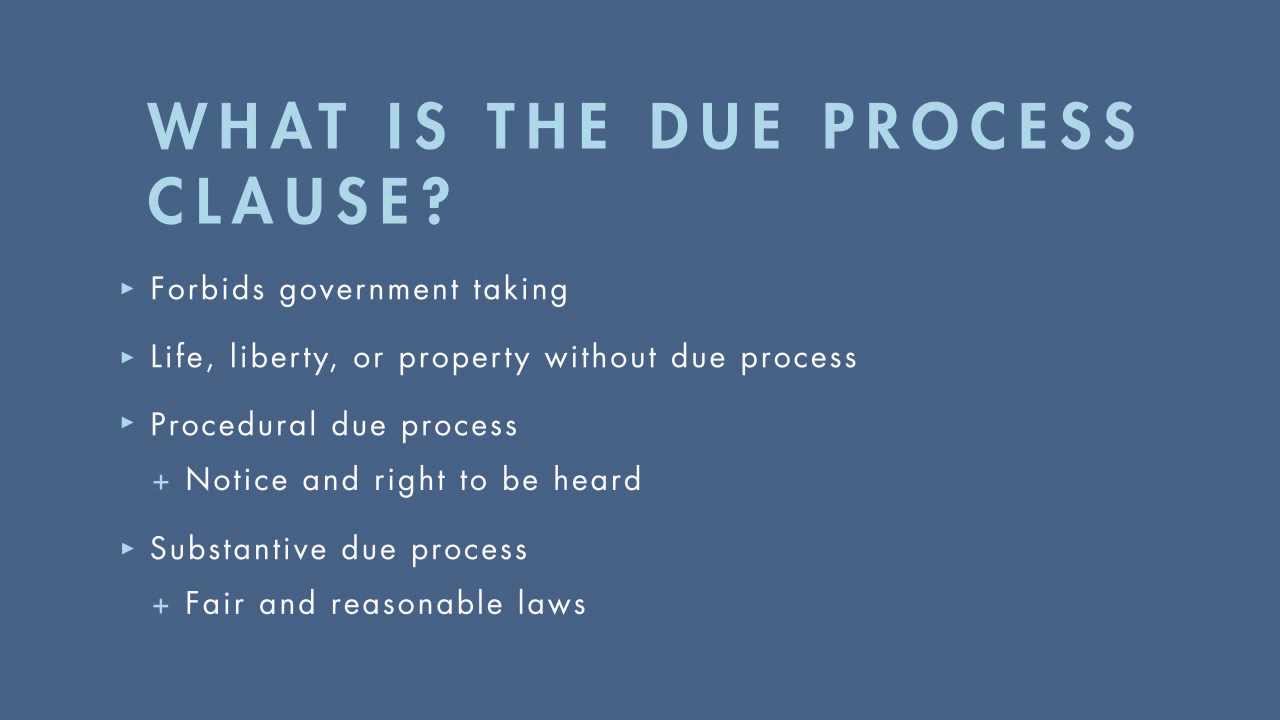

For over a century, federal employees have enjoyed certain due process protections, first codified under the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883. Those protections exist not to coddle bureaucrats, but to ensure that public servants are not punished for political disagreement, whistleblowing, or enforcing inconvenient laws.

The Fifth Amendment guarantees that no person shall be deprived of “life, liberty, or property without due process of law.” While employment is not always considered a property interest, courts have recognized that when statutory job protections are in place, employees are entitled to hearings, notice, and appeal rights.

Stripping those rights through a new executive classification—especially when the basis for firing is political disagreement—creates a serious constitutional due process problem.

Loyalty Tests and First Amendment Landmines

There’s another constitutional landmine buried in this proposal: the First Amendment.

Federal courts have repeatedly ruled that government employees cannot be fired for political affiliation or protected speech, especially if that speech involves matters of public concern. Forcing civil servants to prove their alignment with presidential policy—or risk termination—treads dangerously close to a loyalty oath requirement, something the Supreme Court has consistently rejected.

Would an environmental scientist at the EPA be dismissed for flagging data that conflicts with the president’s energy policy? Would a career analyst at the State Department be forced to publicly support foreign policy strategies they know are flawed?

The First Amendment does not allow the government to coerce speech or punish political dissent. That rule doesn’t disappear inside a federal office building.

Politicizing the Bureaucracy: A Step Toward Executive Overreach

In many ways, this plan is an ideological descendant of a previously proposed change known as Schedule F, which emerged late in Trump’s first term. That initiative also aimed to reclassify tens of thousands of federal employees, removing their civil service protections in favor of at-will employment.

Now revived under a new name, the idea of reshaping the civil service to favor political loyalty is part of a broader effort to consolidate presidential power. And while proponents call it “accountability,” critics—and constitutional scholars—warn it represents something more dangerous: an erosion of institutional checks meant to insulate governance from politics.

The Constitution established three branches of government to protect against exactly this kind of power consolidation. If civil servants become political agents, the courts and Congress may find themselves increasingly isolated—and Americans may find that federal governance no longer operates in the public interest, but the personal interest of whoever holds the Oval Office.

The Government Is Not a Company. It’s a Republic.

The framers of the Constitution knew the danger of centralizing too much power in one person. That’s why they built in a system of professional, accountable, and independent governance—especially among those who carry out the day-to-day work of executing the law.

Calling civil servants “corrupt” because they follow the law instead of political whim is more than just rhetoric. It’s a threat to the legal framework that underpins the federal workforce—and a challenge to the Constitution itself.

The United States government is not supposed to be run like a business. It’s supposed to be run like a republic.