A federal trial is a story told in two parts. For days, the prosecution has painstakingly built its narrative of the case against Ryan Routh, one piece of damning evidence at a time. As the government prepares to rest its case today, that methodical, chilling story is now complete, leaving the courtroom – and the nation – waiting for the far more unpredictable second act: the defense.

How Do You Build a Case for Assassination?

The prosecution’s final witnesses were chosen to leave the jury with an undeniable portrait of lethal intent. An ATF examiner testified that a storage box linked to Routh contained not just ammunition, but “improvised firing mechanisms,” including parts fashioned from rat traps, all spray-painted green for camouflage. This was the work, he argued, of someone “tinkering with new ideas” for destruction.

Following him, an FBI expert in sniper tradecraft described the hideout discovered near the President’s golf course in stark, professional terms.

“…a ‘final firing point’ with ‘multiple shooting lanes.’”

He explained how the rifle could be supported by the fence, a technique he compared to “loophole shooting in combat operations.” The prosecution’s message was clear: this was not a random act of a disturbed individual, but a calculated, military-style ambush.

Can You Cross-Examine Your Way to Reasonable Doubt?

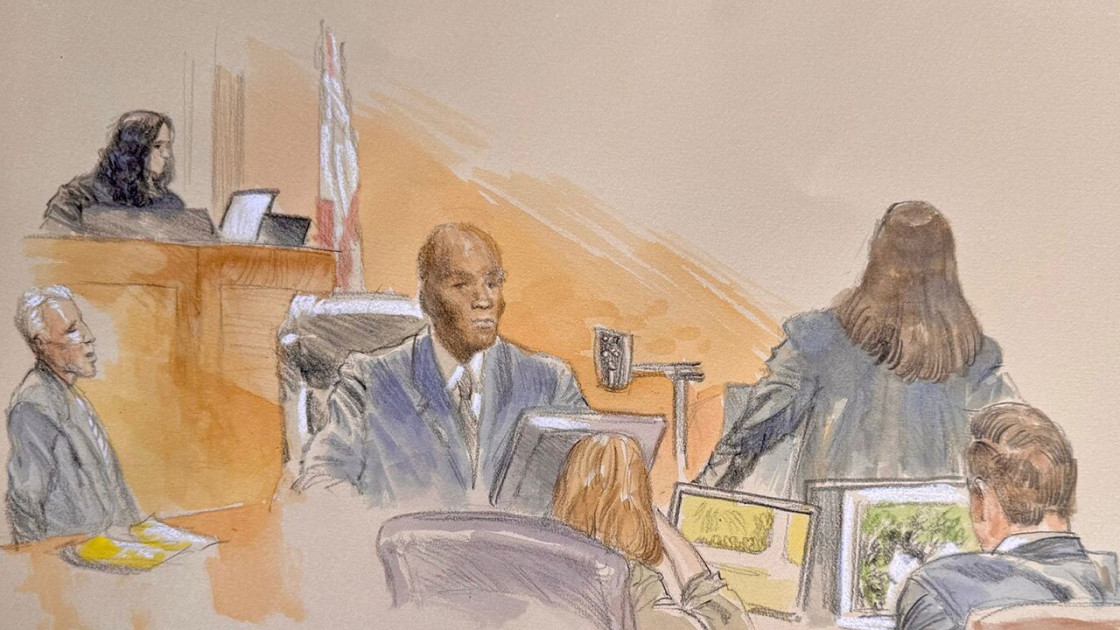

Acting as his own counsel, Routh’s attempts to cross-examine these experts only highlighted the gulf between the state’s case and his own apparent reality. He questioned the sniper expert on whether the red and blue bungee cords in the hideout were well-concealed, a bizarre tangent that the agent calmly dismissed.

With the ATF examiner, Routh focused on whether the unassembled parts of the improvised devices were legal to own – a desperate attempt to parse the legality of individual components while ignoring their collective, deadly purpose. These exchanges have become a hallmark of the trial, showcasing a defendant whose legal strategy remains bafflingly obscure.

Does History Hold a Warning for Self-Representation?

A defendant’s right to represent oneself is constitutionally protected, but it is a path fraught with peril. In 1979, serial killer Ted Bundy acted as his own attorney in his Florida murder trial.

He used the opportunity not for a coherent legal defense, but for courtroom grandstanding and rambling cross-examinations, a spectacle that did nothing to prevent the jury from convicting him and sentencing him to death.

The case remains a stark warning of what can happen when a defendant’s ego eclipses sound legal strategy.

What Happens When the Right to a Defense Becomes a Spectacle?

Now, the burden shifts. The Sixth Amendment guarantees Ryan Routh the right to present a defense, to call his own witnesses, and to tell his side of the story. The judicial system, and Judge Aileen Cannon, must protect this right with absolute fidelity, regardless of how compelling the prosecution’s case may be or how erratic the defendant appears.

This is a profound test of the principles of due process. The defense phase is not a mere formality. It is a constitutional necessity, designed to ensure that a conviction is the result of overwhelming evidence, not just the defendant’s own self-destructive performance in court. The jury has heard the state’s story; now, they must listen to his.