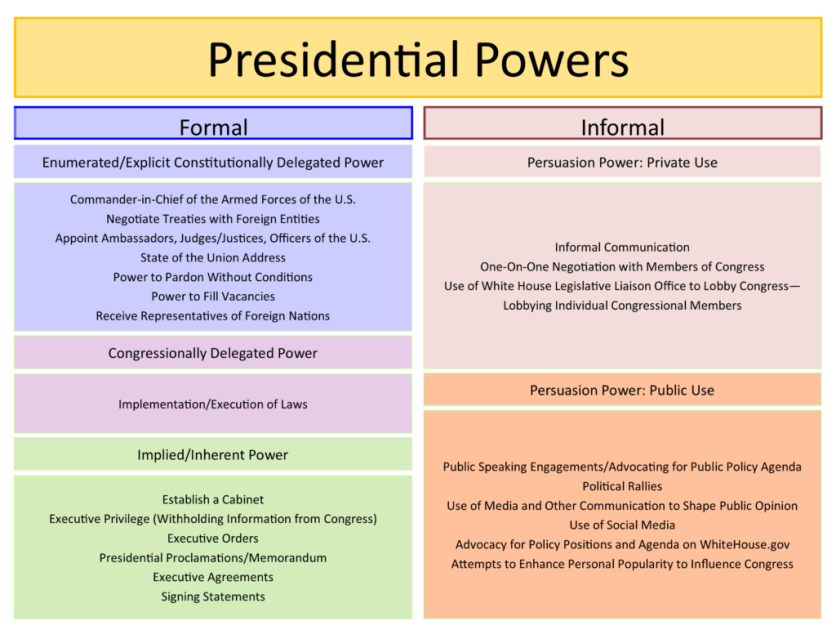

President Trump announced he’d send $2,000 checks to Americans funded by tariff revenue. No Congressional appropriation. No legislative authorization. Just an executive decision to redistribute tax dollars and a prediction that Congress would either approve it or stay silent.

The announcement sparked debate about whether the math works and whether the money actually comes from “foreign countries.” But almost nobody asked the more fundamental question: Can a president simply announce he’s spending money the Treasury doesn’t have authority to spend?

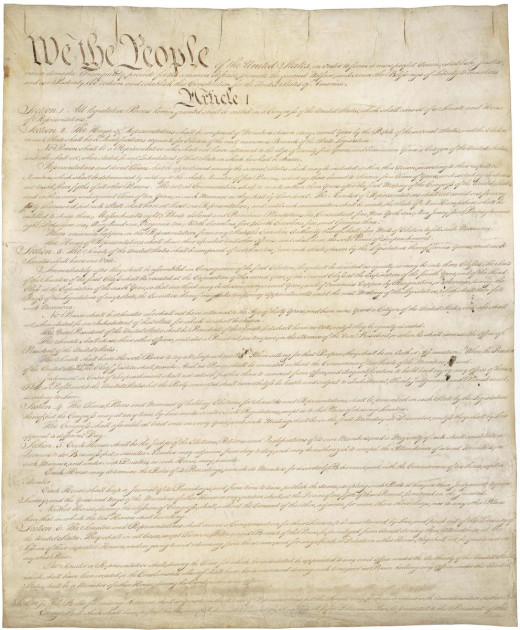

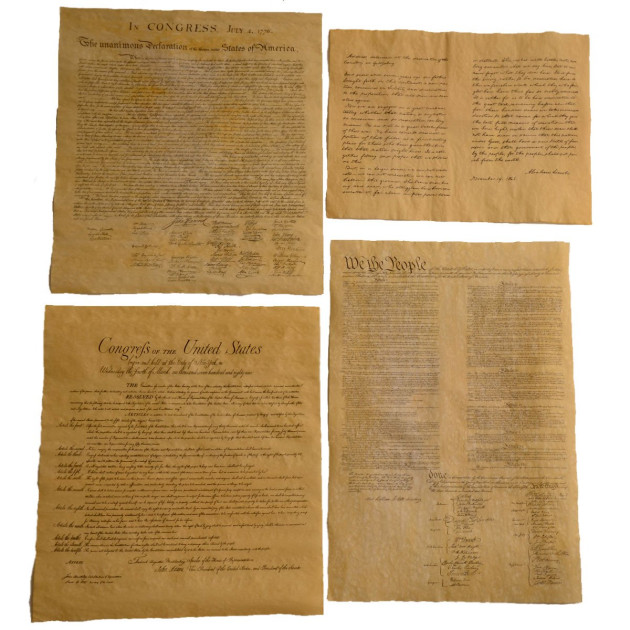

The Constitution answers clearly. Article I, Section 9: “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” That’s not ambiguous language or open to interpretation. It’s an absolute prohibition, written by Founders who feared executive control of government finances above almost everything else.

Two hundred years later, that prohibition exists only on paper. Presidents spend money Congress didn’t appropriate so routinely that Trump’s tariff rebate announcement barely registered as controversial. The appropriations clause has become the constitutional provision nobody enforces – and the story of how that happened reveals everything about how executive power actually works in America.

Why The Founders Made This Rule Iron-Clad

The Constitutional Convention debated many provisions extensively. The appropriations clause wasn’t one of them. It passed with minimal discussion because everyone understood its necessity.

The Founders had lived under a British system where the Crown controlled revenue and spending. That financial power enabled tyranny – the King could fund armies, reward loyalists, and punish opponents without Parliamentary approval. American colonists had fought a revolution partly over taxation without representation, but the deeper issue was spending without authorization.

James Madison explained the logic in Federalist No. 58: “The power over the purse may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people, for obtaining a redress of every grievance, and for carrying into effect every just and salutary measure.”

The weapon only works if Congress actually uses it. The Founders assumed Congress would jealously guard this power because institutional self-interest would compel them to defend their authority. They didn’t anticipate that members of Congress would voluntarily surrender their most powerful check on executive authority.

But they did anticipate one scenario where the rule might break down: emergencies.

Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase: The Original Emergency Spending

Thomas Jefferson faced a genuine dilemma in 1803. Napoleon offered to sell the entire Louisiana Territory for $15 million – roughly $400 billion in today’s GDP-adjusted terms. The deal would double America’s size and eliminate French presence in North America.

Congress hadn’t appropriated money for this purchase. Jefferson had no clear constitutional authority to acquire territory. The deal required immediate acceptance before Napoleon changed his mind.

Jefferson bought Louisiana anyway, then asked Congress to ratify it after the fact. They did, establishing a template that would echo through two centuries: Act during an emergency, create facts on the ground, then secure retroactive approval.

Jefferson himself recognized he’d violated constitutional procedure. He wrote that the purchase was “an act beyond the Constitution” but justified by necessity. That justification – emergency circumstances require constitutional flexibility – would become the eternal excuse for appropriations violations.

The question nobody answered then or since: Who decides what constitutes an emergency? And once that precedent exists, what prevents every president from declaring emergencies to justify spending without appropriations?

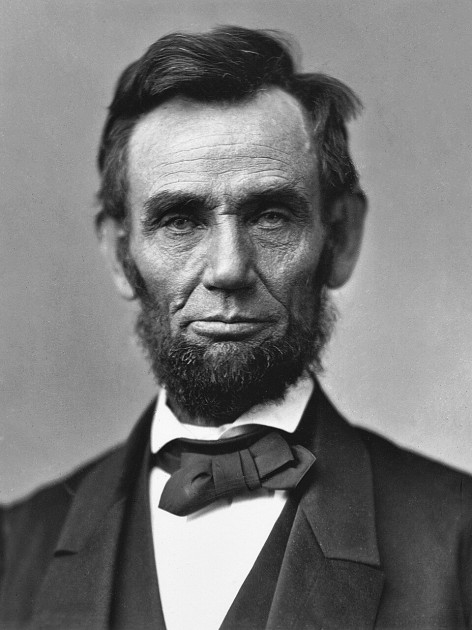

Lincoln Discovers That War Makes Appropriations Optional

Abraham Lincoln took Jefferson’s emergency precedent and expanded it exponentially. When the Civil War began, Congress wasn’t in session. Lincoln couldn’t wait for appropriations.

So he didn’t. Lincoln spent millions mobilizing the Union army, blockading Southern ports, and suspending habeas corpus. All without Congressional authorization. He later explained that he’d acted to preserve the Constitution itself – even if that meant temporarily violating it.

Congress eventually reconvened and retroactively approved most of Lincoln’s expenditures. They had little choice – the money was already spent, the war already underway. Refusing to approve would have meant either impeaching Lincoln mid-war or admitting the Union war effort had been unconstitutionally funded.

Lincoln’s actions established crucial precedents. First, that war emergencies justified bypassing appropriations. Second, that Congress would ultimately approve emergency spending after the fact. Third, that “preservation of the Constitution” could justify temporarily ignoring the Constitution.

Constitutional scholars still debate whether Lincoln was right or simply successful. But the practical impact is undeniable: He proved that presidents who spend first and ask permission later usually face no consequences if they can claim emergency justification.

Every subsequent president learned that lesson.

The Imperial Presidency Builds Its Financial Empire

Theodore Roosevelt didn’t wait for emergencies. He simply started spending money on initiatives he believed Congress should fund but hadn’t.

Roosevelt expanded the executive branch through agencies and programs that lacked full appropriations. When Congress objected, he argued he was executing laws Congress had already passed – even when that execution cost far more than appropriated. His theory: If Congress gave him a responsibility, they implicitly authorized whatever spending that responsibility required.

Woodrow Wilson took this further during World War I. War spending exploded beyond anything Congress had specifically authorized. Wilson interpreted appropriations laws broadly, claiming they gave him discretion to allocate funds across purposes as he deemed necessary for winning the war.

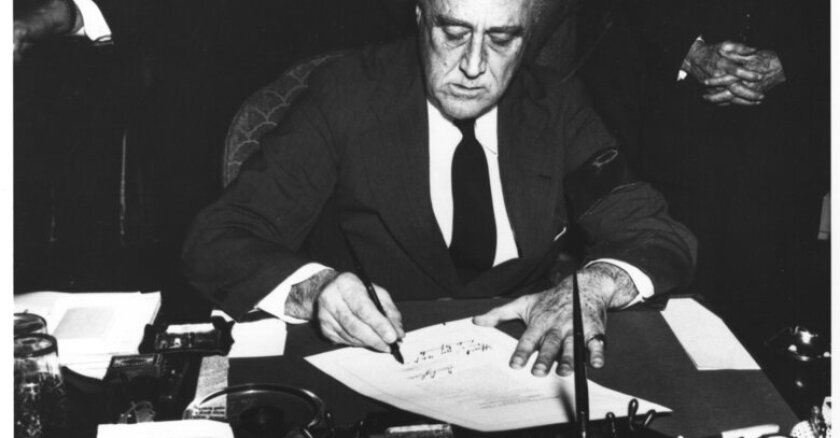

Franklin Roosevelt perfected the art during the New Deal and World War II. He created entire agencies through executive order, funded them through creative interpretations of existing appropriations, and dared Congress to stop him. They rarely did.

The pattern became standard: Presidents propose programs, start implementing them using whatever funding they can creatively reallocate, then pressure Congress to appropriate additional money or risk appearing to undermine initiatives already underway.

By the time Harry Truman sent troops to Korea without a declaration of war, presidential war-making without specific appropriations had become routine. Congress appropriated money for “defense” generally – presidents decided specifically how to wage war.

The appropriations clause still existed in constitutional text. It had ceased to exist in practice.

Nixon’s Impoundment: When Presidents Refuse To Spend

Richard Nixon discovered the flip side of appropriations violations. If presidents could spend money Congress hadn’t appropriated, could they refuse to spend money Congress had appropriated?

Nixon thought so. He impounded – simply refused to spend – roughly $12 billion Congress had appropriated for programs he opposed. His legal theory claimed executive authority to manage spending regardless of Congressional intent.

This overreach finally provoked Congressional action. In 1974, Congress passed the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act. The law created new budget procedures, required presidential budget requests, and limited impoundment authority.

The Act was supposed to reassert Congressional control over appropriations. It failed almost immediately.

The law created process but no enforcement mechanism. It gave Congress tools to challenge presidential spending decisions but required Congress to actually use those tools. And it assumed courts would intervene when presidents violated appropriations requirements.

None of those assumptions proved correct. Presidents continued spending beyond appropriations, Congress rarely challenged them effectively, and courts generally stayed out citing the “political question doctrine” – the idea that appropriations fights between political branches aren’t for judges to resolve.

The Post-9/11 Blank Check That Never Expires

The 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force gave the president authority to use “all necessary and appropriate force” against those responsible for 9/11. Congress appropriated money for that purpose.

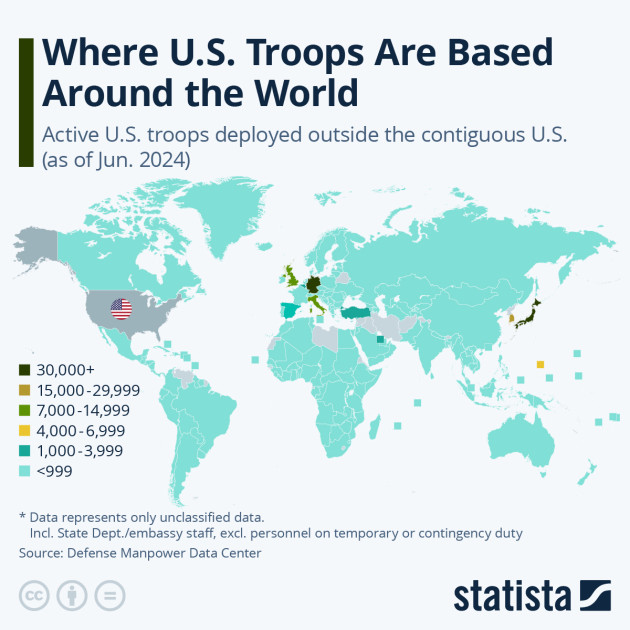

Twenty-four years later, that AUMF remains active. It’s been used to justify military operations in at least seven countries, many against groups that didn’t exist in 2001. The appropriations for “war on terror” have become a permanent blank check for presidents to wage war wherever they claim terrorism threatens.

This represents the complete collapse of appropriations as a check on executive war-making. Congress appropriates money generally for “defense” and “overseas contingency operations.” Presidents decide specifically where to fight, who to target, and how much to spend – all without seeking additional authorization.

The Founders specifically gave Congress war declaration power alongside appropriations authority. Both were meant to check executive militarism. Both have been effectively abandoned through the combination of broad authorizations and even broader appropriations.

Barack Obama’s Libya intervention made this explicit. Obama committed U.S. forces to war without Congressional authorization. When challenged, his administration argued existing defense appropriations provided implicit authority. If Congress didn’t want military operations in Libya, they could specifically prohibit funding for them.

That’s appropriations logic inverted. Instead of presidents needing explicit appropriations to spend, they now claim they can spend defense money on any operation unless Congress explicitly prohibits it. The constitutional burden has shifted entirely.

Trump’s Wall Emergency: Spending Through Creative Reprogramming

Donald Trump wanted $5.7 billion for a border wall. Congress appropriated $1.4 billion. Trump declared a national emergency and reprogrammed $3.6 billion from military construction funds to build the wall anyway.

Lower courts initially blocked this, ruling Trump lacked authority to reprogram funds Congress had explicitly denied. But the Supreme Court allowed construction to continue during appeals. By the time litigation concluded, much of the money was already spent and wall sections were built.

This became the template for modern appropriations violations: Declare an emergency, identify existing appropriations that can be creatively reinterpreted, start spending immediately, litigate while spending continues, accomplish your goal before courts can effectively stop you.

The legal theory supporting this approach is breathtaking in its implications. If presidents can declare emergencies and reprogram any appropriated funds toward that emergency, appropriations specificity becomes meaningless. Congress appropriates money for military housing, but presidents can spend it on walls. Congress funds foreign aid, but presidents can withhold it to pressure investigations. Congress appropriates disaster relief, but presidents can direct it toward politically favorable states.

Every one of those examples has happened in recent years. None resulted in meaningful accountability.

Obama’s Healthcare Subsidies: Spending Without Appropriation

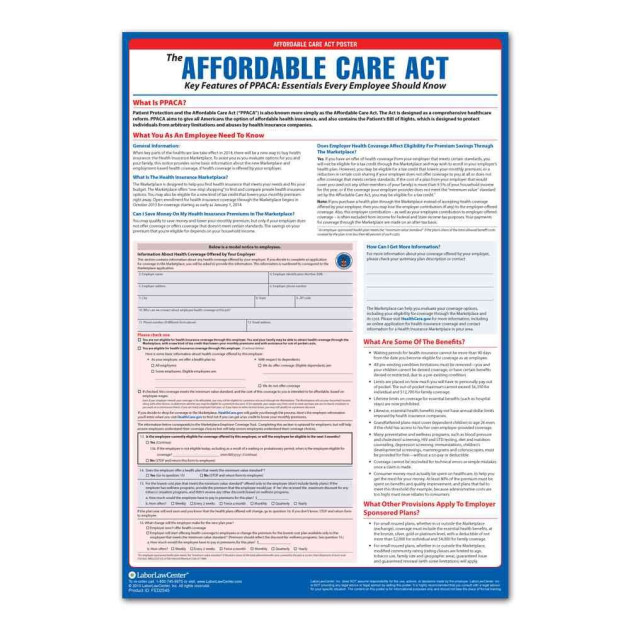

The Affordable Care Act included cost-sharing subsidies to help low-income Americans afford insurance. The law authorized the subsidies but didn’t explicitly appropriate money for them.

The Obama administration spent $7 billion on these subsidies anyway, claiming they were covered by a separate permanent appropriation for tax refunds. This legal interpretation was creative at best.

The House of Representatives sued, arguing the spending violated the appropriations clause. A federal judge agreed in 2016, ruling the payments were unconstitutional because Congress hadn’t appropriated funds for them.

The Obama administration appealed. The Trump administration eventually ended the subsidies – not because of the court ruling, but because Trump opposed the program politically. The constitutional question was never definitively resolved.

This case reveals how appropriations violations work in practice. Presidents spend money, litigation takes years, money gets spent during appeals, and by the time courts rule the spending has already occurred. Even when courts find spending unconstitutional, there’s rarely an effective remedy beyond stopping future payments.

The deterrent value approaches zero. Presidents know they can spend for years before facing any judicial consequence, and even then the consequence is merely “stop doing it” rather than any personal or political penalty.

Why Courts Won’t Enforce The Appropriations Clause

Federal judges have repeatedly declined to police appropriations violations. Their reasons reveal why the constitutional check has failed.

First, standing problems. Who has the right to sue when presidents spend money without appropriations? Individual taxpayers generally lack standing – their injury is too diffuse. Members of Congress face political question barriers – courts say appropriations fights are for political branches to resolve.

Second, remedy problems. If a court finds spending unconstitutional, what happens? Order the money returned? From whom? Halt programs mid-operation? Courts are reluctant to issue orders that create chaos or that presidents might ignore.

Third, political question doctrine. Judges generally view appropriations as a matter between president and Congress. If Congress doesn’t like how presidents spend money, Congress has remedies – cutting other funding, refusing confirmations, impeachment. Courts shouldn’t intervene in political disputes between branches.

The 1998 line-item veto case is the exception proving the rule. The Supreme Court struck down the Line Item Veto Act, which gave presidents authority to cancel specific appropriations items. The Court ruled this violated the Constitution’s presentment clause – not the appropriations clause.

The decision is notable for what it didn’t say. The Court didn’t address all the ways presidents already effectively exercised line-item veto power through impoundment, reprogramming, and creative interpretation. It struck down a formal statutory grant of power while ignoring the informal accumulation of the same power through precedent.

Congressional Surrender: The Willing Abandonment of Power

The most important reason appropriations violations continue is that Congress allows them. In theory, Congress has powerful tools to enforce appropriations limits.

Congress could refuse to confirm presidential appointees until spending violations stop. It could cut funding for White House operations. It could hold executive officials in contempt. It could impeach presidents who systematically violate appropriations law.

Congress does none of these things. Why?

Partisan incentives explain most of it. When the president is from your party, members of Congress defend executive flexibility and creative interpretations. When the president is from the other party, they complain about constitutional violations but rarely use their actual powers to stop them.

This creates a ratchet effect. Each party’s president expands spending authority, the other party objects but doesn’t stop it, then when they reclaim the presidency they use the precedent their opponents established. Executive spending power expands regardless of which party holds office.

There’s also an institutional problem. Modern members of Congress often want presidents to spend money Congress hasn’t appropriated. It lets them avoid difficult votes while still delivering benefits to constituents. Members can criticize deficit spending publicly while privately appreciating that executive spending accomplishes policy goals without requiring them to take responsibility.

The Founders assumed Congress would defend its institutional prerogatives regardless of partisan advantage. They were wrong. Partisanship has proven stronger than institutional loyalty in almost every case.

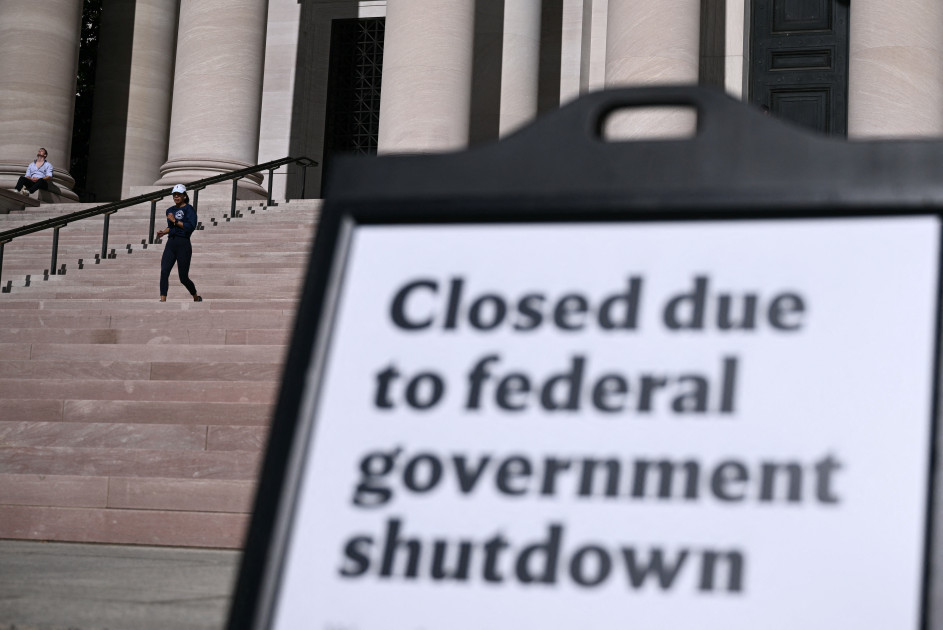

Shutdown Politics Reveal The Appropriations Void

Government shutdowns should demonstrate that appropriations matter. Without Congressional authority to spend, government operations should halt entirely.

They don’t. Presidents claim authority to continue “essential” operations during shutdowns. They decide which programs are essential. They find legal theories to keep spending money even without appropriations.

The 2018-2019 shutdown lasted 35 days. The 2025 shutdown lasted 40 days. During both, presidents made decisions about which appropriated programs to fund and which to withhold. Trump withheld SNAP benefits despite existing appropriations, claiming shutdown conditions justified the withholding.

This inverts appropriations logic completely. The clause says presidents can’t spend without appropriations. Shutdown fights reveal presidents can also refuse to spend money Congress has appropriated, choosing which laws to execute based on political priorities.

If presidents have discretion both to spend money not appropriated and to withhold money that is appropriated, the appropriations clause provides zero constraint on executive spending decisions. It becomes purely advisory – a suggestion Congress makes about how money should be spent that presidents can ignore whenever they claim sufficient justification.

Emergency Declarations As Permanent Appropriations Authority

The National Emergencies Act allows presidents to declare emergencies and invoke special statutory authorities. Currently, 42 national emergencies are active. Some date to the 1970s.

Each emergency declaration potentially unlocks appropriations flexibility. Presidents claim emergency conditions justify spending money Congress wouldn’t normally appropriate or reprogramming funds Congress designated for other purposes.

The word “emergency” has expanded to cover almost any situation a president deems urgent. Border security, trade disputes, cyber threats, pandemic responses – all have been declared emergencies justifying expanded spending authority.

Congress technically could terminate these emergencies through joint resolutions. They rarely do, because doing so requires overriding a presidential veto with two-thirds majorities in both chambers.

So emergency authorities accumulate. Each president inherits the emergencies previous presidents declared and adds new ones. The baseline of “normal” presidential spending authority keeps expanding as emergencies become permanent.

The Founders intended appropriations as a check on executive power during normal times. They understood emergencies might require flexibility. But they didn’t anticipate emergencies that last fifty years or presidents who treat emergency declarations as routine tools for circumventing Congressional appropriations.

The International Comparison: How Other Democracies Enforce This

Parliamentary democracies generally don’t face appropriations problems because the executive comes from the legislature. If Parliament doesn’t appropriate money, the government falls and new elections occur. The incentive structure ensures appropriations alignment.

Presidential systems similar to America’s often include stronger judicial enforcement of appropriations requirements. Constitutional courts in countries like Germany or South Africa actively police executive spending, reviewing whether expenditures align with legislative authorizations.

The United States is unusual in having presidential systems with weak judicial enforcement and a legislature unwilling to defend its own powers. This combination creates maximal opportunity for appropriations violations with minimal accountability.

American exceptionalism in this case means exceptionally poor enforcement of constitutional limits on executive spending. Other democracies manage to maintain appropriations discipline. The U.S. abandoned it decades ago.

Student Loans: When SCOTUS Actually Enforced Limits

The Biden administration’s student loan forgiveness plan proposed canceling up to $20,000 in federal student debt per borrower at a cost of roughly $400 billion. The administration claimed authority under the HEROES Act, a 2003 law allowing the Education Secretary to modify student loan terms during national emergencies.

This was appropriations violation at massive scale. Congress had never appropriated $400 billion for debt cancellation. The administration argued existing statutory authority provided implicit appropriations authority.

The Supreme Court disagreed, striking down the plan 6-3 in Biden v. Nebraska. The Court ruled the HEROES Act didn’t clearly authorize debt cancellation of this magnitude and that major policy decisions of vast economic significance require clear Congressional authorization.

This decision appeared to reinforce limits on executive spending. But it’s telling which spending the Court chose to block. Biden’s student loan plan was progressive policy broadly popular with his base but opposed by conservatives and moderates concerned about costs and fairness.

Trump’s border wall emergency, which also spent appropriated funds for unauthorized purposes, received gentler treatment from the same conservative Court majority. The pattern suggests judicial enforcement depends partly on whether judges agree with the underlying policy.

That’s not how constitutional limits should work. If appropriations clause violations merit judicial intervention, they should merit it regardless of whether spending goes toward walls or student debt. Selective enforcement based on policy preferences undermines whatever deterrent effect judicial review might provide.

What Actual Enforcement Would Require

Fixing appropriations violations would require actions no institution appears willing to take.

Judicial intervention: Courts would need to establish clear standing for appropriations challenges, eliminate political question deference, and create meaningful remedies for violations. This would require overturning decades of precedent and accepting responsibility for policing political branch conflicts.

Congressional backbone: Congress would need to defend institutional prerogatives regardless of partisan advantage. Members would need to value Congressional power more than supporting their party’s president. They’d need to use their actual powers – impeachment, confirmations, funding cuts – to enforce appropriations limits.

Constitutional amendment: The most effective solution would be constitutional amendment adding enforcement mechanisms to the appropriations clause. Criminal penalties for officials who spend without authorization. Automatic standing for appropriations challenges. Mandatory judicial review with expedited procedures.

None of these will happen. Courts are institutionally reluctant to intervene in political disputes. Congress has proven consistently unwilling to defend its powers against executive encroachment. Constitutional amendments require supermajorities impossible to achieve in polarized times.

The realistic answer is that nothing will change. Appropriations violations will continue and probably expand. Each precedent makes the next violation easier to justify.

The Authoritarian Logic Endpoint

If presidents can spend money without appropriations, what constitutional limit on executive power remains meaningful?

The appropriations clause was supposed to be the ultimate check. The Founders designed Congress as the most powerful branch specifically because it controlled government finances. Presidents couldn’t wage war, implement policy, or reward supporters without Congressional money.

Once that check disappears, executive power has no practical limit beyond what courts might prohibit in specific cases or what Congress might successfully impeach for. Neither has proven effective at constraining modern presidents.

The authoritarian endgame isn’t presidents who ignore all laws. It’s presidents who obey laws they agree with and find creative justifications for circumventing laws they oppose. It’s legal theories elastic enough to justify whatever outcome the president wants. It’s checks and balances that exist on paper but not in practice.

That’s not a warning about a hypothetical future. That’s a description of how appropriations work right now. Presidents spend money Congress didn’t appropriate, refuse to spend money Congress did appropriate, and face no meaningful consequences because the institutions designed to check them have voluntarily abdicated that responsibility.

Trump’s Tariff Checks In Historical Context

Return to Trump’s $2,000 tariff rebate announcement. View it through the lens of two centuries of appropriations violations.

Trump isn’t doing anything unprecedented. He’s following a pattern established by Jefferson, perfected by Lincoln, normalized by FDR, and practiced by every subsequent president. He’s claiming emergency-adjacent authority (tariff revenue from trade policy) to justify spending without explicit appropriation.

The announcement assumes either that Congress will appropriate the money when presented with a fait accompli, or that Congress will simply stay silent and allow spending to proceed. Both assumptions rest on 200 years of precedent showing Congress usually does exactly that.

Whether the $2,000 checks ever materialize is almost beside the point. The real significance is that a president can announce a spending program of this magnitude without possessing appropriations authority and face no immediate challenge from Congress or courts.

That’s not how the appropriations clause is supposed to work. But it’s exactly how appropriations work in practice.

The Constitutional Text That Nobody Reads

Article I, Section 9, Clause 7 of the United States Constitution remains in force. It still says “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.”

We still teach that provision in civics classes. Constitutional scholars still cite it as a fundamental limit on executive power. The text is clear and unambiguous.

It’s also completely unenforced. Presidents violate it regularly. Congress tolerates violations. Courts decline to intervene. The appropriations clause exists as constitutional decoration – something we point to when explaining how government should work, while ignoring how it actually works.

The Founders would be horrified. They viewed Congressional control of spending as the essential protection against executive tyranny. Madison called it “the most complete and effectual weapon” for checking presidential power.

That weapon lies unused. Not because it was taken away, but because Congress voluntarily set it down and presidents picked it up. The appropriations clause failed not through constitutional amendment or judicial reinterpretation, but through institutional surrender.

Two hundred years of presidents discovered that spending money without authorization works if nobody stops you. And for two hundred years, nobody stopped them.

The question isn’t whether presidents will keep violating the appropriations clause. The question is whether we’ll keep pretending it means anything at all.