Christopher Moynihan was among the first rioters to breach the Capitol on January 6, 2021. He was sentenced to 21 months in prison but didn’t serve his full term because President Trump pardoned him.

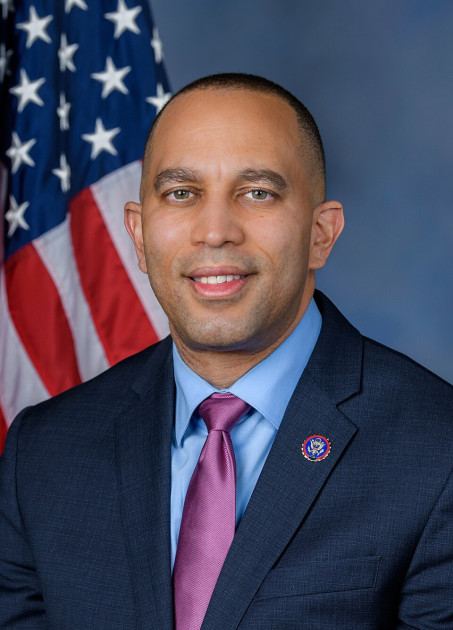

Last week, he was charged with threatening to assassinate House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, texting “I cannot allow this terrorist to live. Even if I am hated he must be eliminated. I will kill him for the future.”

He’s just the latest in a growing list of pardoned January 6 defendants who’ve been arrested again for new crimes – from child pornography to drunk driving deaths to plotting to kill FBI agents.

This raises the starkest possible question about presidential pardon power: when does constitutional mercy become reckless endangerment of public safety, and does the President bear any responsibility for crimes committed by people he freed?

At a Glance

- Christopher Moynihan, pardoned by Trump for Jan. 6 participation, charged with threatening to kill Hakeem Jeffries

- Moynihan texted threats saying Jeffries “must be eliminated” and “I will kill him for the future”

- Multiple pardoned Jan. 6 defendants have been arrested for new crimes: child pornography, drunk driving deaths, plotting to kill FBI agents, home invasion

- Jeffries warned that “many of the criminals released have committed additional crimes throughout the country”

- At stake: whether presidential pardon power includes accountability for foreseeable consequences of mass clemency

The Threat Against Jeffries

According to the criminal complaint from Dutchess County prosecutors in New York, Moynihan sent text messages Friday threatening Jeffries’ life to an unknown associate. The texts referenced the House Democratic leader attending an event in New York City and stated his explicit intention to carry out an assassination.

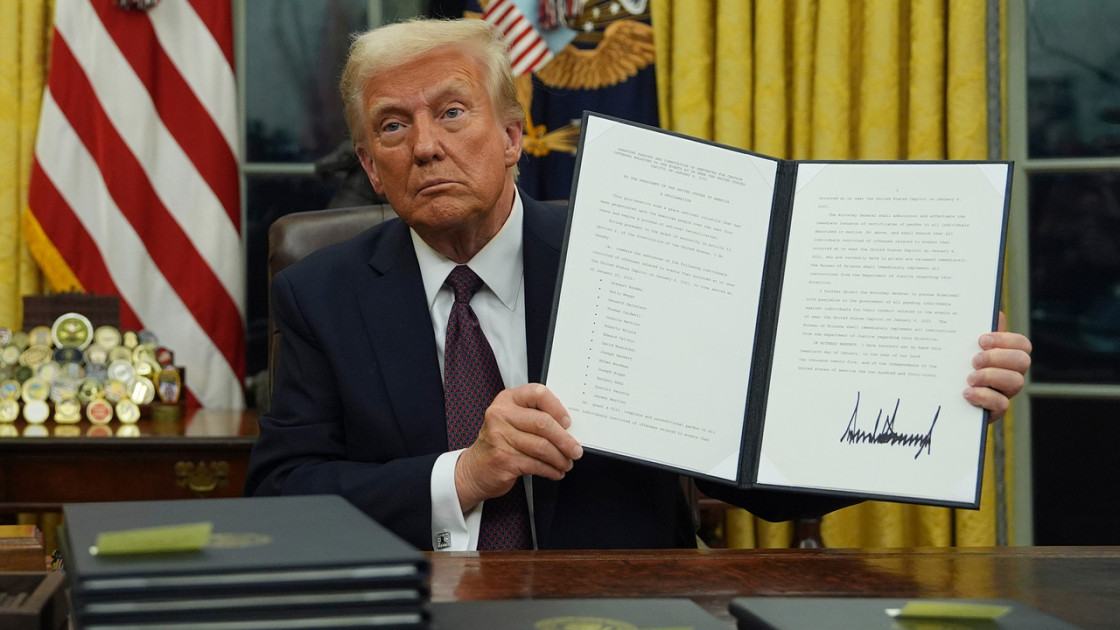

Moynihan was among the first group of rioters to break into the U.S. Capitol on January 6 and was sentenced to 21 months in prison. He never served his full sentence because Trump pardoned him along with hundreds of other January 6 defendants in one of the most controversial exercises of presidential clemency power in American history.

Jeffries responded with a statement thanking law enforcement for their “swift and decisive action to apprehend a dangerous individual who made a credible death threat against me with every intention to carry it out.” But he also noted the broader pattern: “Since the blanket pardon that occurred earlier this year, many of the criminals released have committed additional crimes throughout the country. Unfortunately, our brave men and women in law enforcement are being forced to spend their time keeping our communities safe from these violent individuals who should never have been pardoned.”

“I cannot allow this terrorist to live. Even if I am hated he must be eliminated. I will kill him for the future.” – Christopher Moynihan’s text message threatening Rep. Hakeem Jeffries

The Growing List of Re-Offenders

Moynihan isn’t an isolated case. The pattern of pardoned January 6 defendants committing new crimes is extensive and disturbing:

Robert Keith Packer, infamous for wearing a “Camp Auschwitz” sweatshirt inside the Capitol, was arrested in a dog-biting incident last month.

Another pardoned defendant was convicted on child pornography charges.

Another pardoned rioter was convicted of plotting to kill FBI agents just two weeks before Moynihan’s arrest.

Zachary Jordan Alam was convicted last week in connection with a home invasion, months after receiving his January 6 pardon.

Andrew Taake pleaded guilty to soliciting a minor weeks after receiving his pardon.

Emily Hernandez was sentenced to 10 years in prison for driving drunk and killing a passenger in another car, weeks after being pardoned.

Brent Holdridge was arrested in May in connection with alleged thefts of industrial copper.

Matthew W. Huttle was fatally shot by a sheriff’s deputy in January after resisting arrest during a traffic stop, shortly after receiving his presidential pardon.

This isn’t a few isolated incidents – it’s a pattern suggesting that mass pardons for people convicted of violent crimes predictably lead to more crime.

The Constitutional Authority Behind Pardons

Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution gives the President essentially unlimited pardon power for federal offenses: “The President shall have Power to grant Reprieves and Pardons for Offences against the United States, except in Cases of Impeachment.”

That power is nearly absolute. The President doesn’t need to justify pardons, doesn’t need approval from Congress or courts, and can pardon individuals or entire categories of offenders. The only limits are that pardons can’t prevent impeachment and can only apply to federal crimes, not state offenses.

The Framers gave presidents this broad authority deliberately. Alexander Hamilton explained in Federalist 74 that the pardon power provides “easy access to exceptions in favor of unfortunate guilt” and allows mercy to temper justice. He argued that “humanity and good policy conspire to dictate, that the benign prerogative of pardoning should be as little as possible fettered or embarrassed.”

But Hamilton also wrote that the pardon power would be exercised by a president “who may be presumed to have the attributes of wisdom and virtue.” The assumption was that presidents would use pardons judiciously, showing mercy in appropriate cases while maintaining public safety.

The Constitution gives presidents unlimited pardon power but assumes they’ll exercise it responsibly. What happens when that assumption proves wrong?

The Accountability Problem

Here’s the constitutional problem this situation exposes: presidents have essentially unlimited power to grant pardons, but they bear no legal accountability for what pardoned individuals do afterward.

If a president pardons someone who then commits murder, the president faces no legal consequences. He can’t be sued by victims. He can’t be criminally charged for releasing dangerous individuals. His only accountability is political – voters can vote him out, Congress could theoretically impeach him, or public opinion can damage his reputation.

That political accountability works when presidents exercise pardon power sparingly and carefully. It breaks down when presidents issue mass pardons or blanket clemency to entire categories of offenders without individual case review.

Trump’s January 6 pardons were controversial precisely because they were categorical rather than individualized. He pardoned hundreds of people convicted of various crimes – from simple trespassing to assaulting police officers with dangerous weapons – without apparent consideration of each defendant’s specific conduct, criminal history, or likelihood of reoffending.

Critics warned at the time that this approach would inevitably result in dangerous individuals being released. Defenders argued that January 6 defendants were political prisoners who shouldn’t have been prosecuted at all. The emerging pattern of recidivism suggests the critics’ concerns were well-founded.

The Precedent Problem

Presidential pardons aren’t unprecedented, and neither are cases where pardoned individuals commit new crimes. But the scale and pattern here are unusual.

Presidents typically grant pardons after careful review – either individual petitions reviewed by the Office of the Pardon Attorney, or high-profile cases where the president personally considers the circumstances. Even controversial mass pardons (like Gerald Ford pardoning Vietnam draft evaders or Jimmy Carter extending that pardon) involved non-violent offenses where recidivism risk was low.

Trump’s January 6 pardons were different: hundreds of people convicted of violent crimes, many with minimal individual consideration, released based primarily on political loyalty rather than rehabilitation or remorse. That created foreseeable risks that are now materializing.

The precedent this sets is concerning: if presidents can issue blanket pardons to political supporters convicted of violent crimes without facing meaningful accountability when those individuals reoffend, the pardon power becomes a tool for presidents to build loyalty among supporters who break laws on their behalf.

What the Founders Would Say

Hamilton’s Federalist 74 defense of the pardon power assumed presidents would exercise it with “caution” and “scrupulousness.” He wrote that the power was necessary for “unfortunate guilt” and to provide “mitigation of the rigor of the law” in appropriate cases.

But Hamilton also assumed presidents would be constrained by concern for their reputation and legacy. He wrote that “the dread of being accused of weakness or connivance” would prevent presidents from abusing the pardon power recklessly.

That assumption doesn’t hold when a president views January 6 defendants as political allies rather than criminals, and when his base celebrates the pardons rather than questioning them. Political accountability only works when the president’s supporters care about the consequences of his actions.

Madison would likely worry about any unchecked power, even one the Framers deliberately left unchecked. He’d probably argue that Congress should have some role in reviewing or constraining mass pardons, though the Constitution doesn’t provide for that.

Jefferson would focus on the victims – in this case, people like Hakeem Jeffries who are now threatened by pardoned criminals. He’d argue that government’s primary responsibility is protecting citizens’ rights and safety, and that pardon power shouldn’t be exercised in ways that endanger innocent people.

The Public Safety vs. Mercy Trade-off

The pardon power exists because the criminal justice system is imperfect. Sometimes people are wrongly convicted. Sometimes sentences are too harsh. Sometimes circumstances change in ways that make continued punishment unjust. Presidential pardons provide a safety valve for correcting these problems.

But pardons also create public safety risks when dangerous individuals are released early. That’s why presidents traditionally exercise pardon power carefully – weighing mercy against public safety, considering rehabilitation and remorse, and reviewing individual circumstances.

Mass categorical pardons eliminate that careful balancing. When you pardon everyone convicted of January 6 offenses regardless of their specific conduct or likelihood of reoffending, you inevitably release some people who remain dangerous.

“We are going to have law and order.” – President Trump, repeatedly, while pardoning criminals who then commit more crimes

The irony is sharp: Trump campaigns on “law and order” while giving “get out of jail free” cards to people who proceed to break more laws. That irony would be merely political if it didn’t have real victims – Hakeem Jeffries receiving death threats, a passenger killed by a drunk driver, children victimized by sexual predators, FBI agents targeted for murder.

The Constitutional Reality of Unchecked Power

The Constitution gives presidents unlimited pardon power with essentially no accountability mechanisms beyond political pressure and reputation. That worked reasonably well for over two centuries because presidents generally exercised the power responsibly.

What we’re learning now is what happens when a president doesn’t care about reputation constraints, when his political base celebrates rather than questions his pardons, and when he views clemency as a tool for rewarding loyalty rather than correcting injustice.

The pattern of pardoned January 6 defendants committing new crimes was foreseeable. Critics warned about it. Law enforcement worried about it. And now it’s happening – not just in isolated incidents, but as a clear pattern of recidivism.

There’s no constitutional remedy for this. Congress can’t reverse pardons. Courts can’t review them. The only check is political: voters deciding whether they care that pardoned criminals are threatening members of Congress, committing sex crimes, killing people drunk driving, and plotting to murder FBI agents.

That’s the constitutional reality of unlimited presidential pardon power: it works when exercised responsibly and fails catastrophically when it’s not. And when it fails, the people who pay the price aren’t presidents – it’s Hakeem Jeffries receiving death threats, passengers killed by drunk drivers, and communities forced to deal with violent criminals released for political reasons.

The Constitution trusts presidents with this enormous power. Christopher Moynihan’s text messages threatening to assassinate a congressional leader suggest that trust isn’t always warranted – but the Constitution provides no remedy when it’s betrayed beyond voting for someone different next time.