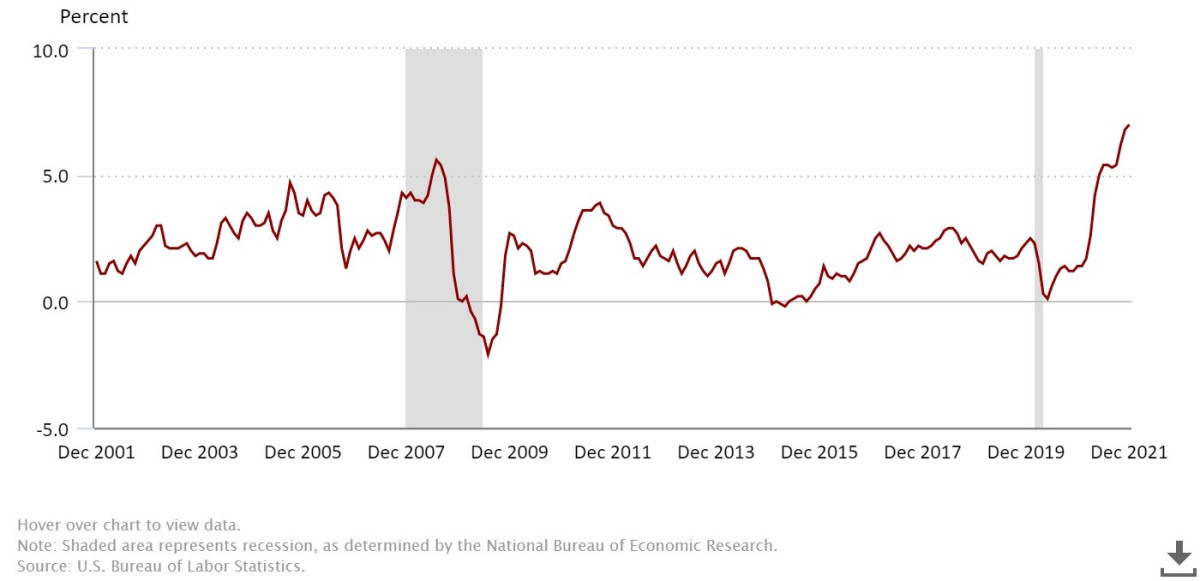

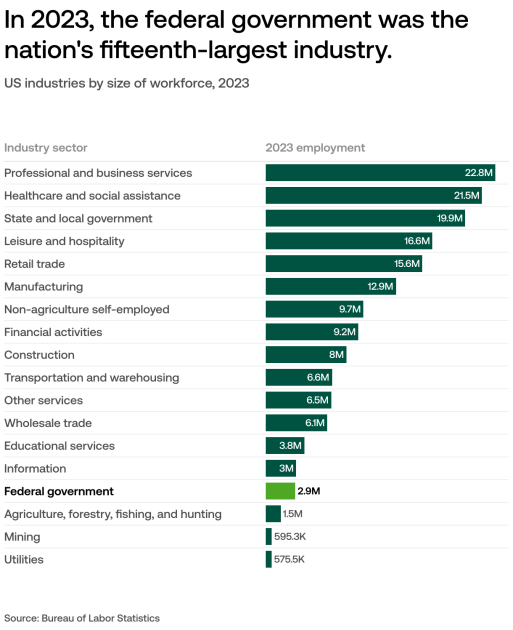

The Bureau of Labor Statistics team that produces inflation estimates was sent home during the government shutdown, potentially leaving 70 million Social Security recipients in limbo about their cost-of-living adjustments. The Trump administration quickly reversed course on that particular data suppression after recognizing the political backlash.

But according to critics, it’s just one example of a broader pattern: government data that’s been collected for decades is disappearing – scrubbed from websites, discontinued as surveys, or simply no longer gathered because it conflicts with administration priorities.

The constitutional question underneath all the outrage about “Orwellian” data suppression is actually straightforward: does the President have authority to decide what information the federal government collects and publishes, or does the public have a constitutional right to data the government has traditionally provided?

At a Glance

- BLS inflation team initially furloughed during shutdown, threatening Social Security COLA announcement, then brought back after backlash

- Multiple data collection programs have been eliminated or suspended: food insecurity surveys, EPA greenhouse gas reporting, drug abuse emergency data, CDC injury statistics

- Officials who provided data contradicting Trump’s claims have been fired, including BLS head and Defense Intelligence Agency director

- References to climate change, slavery, and Japanese American internment removed from some national parks and Smithsonian exhibits

- At stake: whether executive authority over agencies includes power to eliminate data collection that informs policy debates

The Data That’s Disappearing

The list of discontinued or suspended data collection programs is extensive. An annual survey that helped shape federal policy to combat food insecurity and hunger for low-income Americans has been abandoned. This happened before Congress passed legislation making major reductions to SNAP (food stamps), making it harder to track whether those cuts are causing increased hunger.

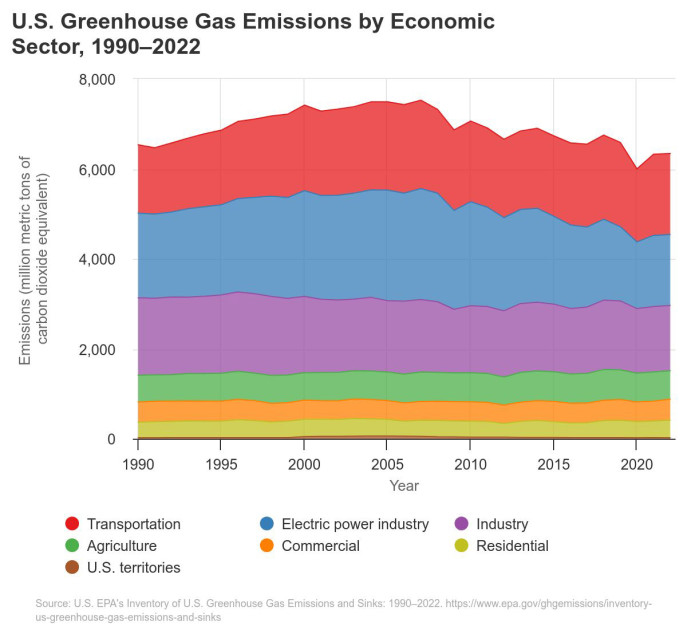

The EPA is ending the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program that required pollution reporting from power plants and iron and steel facilities – exempting some 8,000 entities nationwide. The agency is also suspending pollution reporting mandates for petroleum companies until 2034. This eliminates baseline data needed to measure whether future environmental policies are working.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration discontinued its Drug Abuse Warning Network that recorded emergency department visits related to substance use and emerging drug trends. The 17-member team managing the National Survey on Drug Use and Health has been laid off. Policymakers will now make decisions about the opioid crisis and drug policy with less information about what’s actually happening.

The CDC fired about 170 employees at the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, which collects data on car crashes, drownings, gun violence, homicides and traumatic brain injuries.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration stopped publishing new content on its climate.gov website after firing all 10 staff members. That site provided information about changing weather patterns, drought conditions, and greenhouse gas emissions that farmers, emergency planners, and local governments used for planning.

The Officials Who Got Fired for Providing Data

Government officials who provided information contrary to Trump’s perception of reality have been terminated. The head of the Bureau of Labor Statistics was fired after providing employment data showing a slowdown in the labor market. The director of the Defense Intelligence Agency was removed after a preliminary report about the limited impact of bombing Iran’s nuclear sites contradicted Trump’s claims about the operation’s success.

This creates a chilling effect: career officials see what happens when data contradicts presidential messaging, and they adjust accordingly. Either they stop collecting certain data, or they become more selective about what gets published and when.

At the Department of Justice, the National Law Enforcement Accountability Database is no longer collecting information about misconduct by federal law enforcement officials. A December report had cited 4,790 misconduct incidents between 2018 and 2023, with nearly 1,500 federal officers suspended, fired or resigned while under investigation, and more than 300 convicted of crimes. That database is now gone.

The Constitutional Authority Question

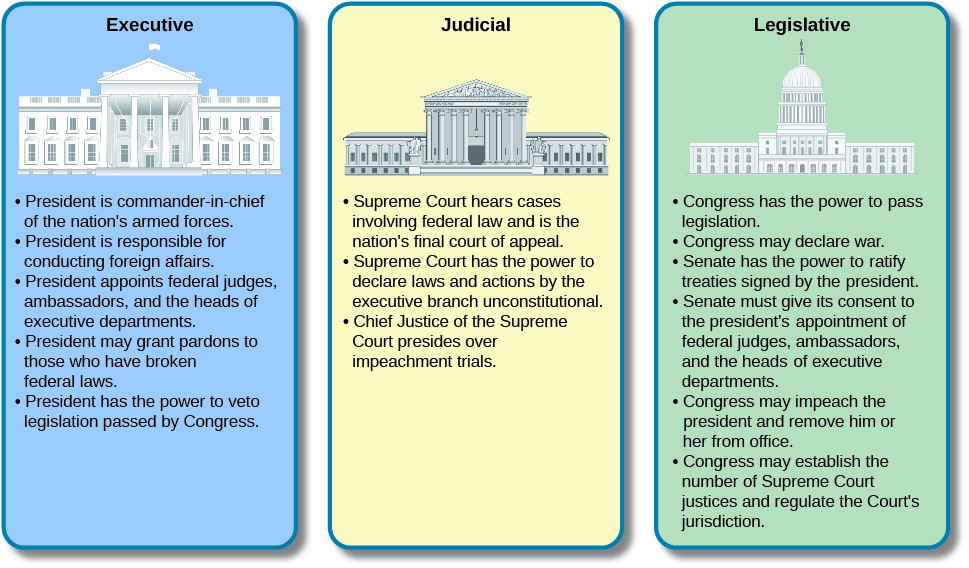

Here’s the core constitutional question: does the President have authority to decide what data the federal government collects and publishes?

The short answer is: largely yes. Article II makes the President the chief executive officer of the federal government. He appoints agency heads who oversee data collection. Congress appropriates money for those agencies, but absent specific statutory requirements to collect particular data, the executive branch has broad discretion over what information to gather and publish.

Some data collection is mandated by statute – the Census every ten years, for example, is required by the Constitution itself. Other data collection programs are required by specific laws Congress has passed. But much of what federal agencies publish – climate data, injury statistics, drug abuse trends – exists because past administrations decided it was useful, not because it’s legally required.

That means a new administration can discontinue programs previous administrations started, as long as they’re not violating specific statutory mandates. The Trump administration isn’t breaking the law by firing the team that ran climate.gov or ending the Drug Abuse Warning Network. Those were executive branch initiatives that can be ended by executive decision.

The Constitution doesn’t guarantee public access to government data beyond what specific statutes require. The President has enormous discretion over what information federal agencies collect and release.

The Historical and Museum Content Changes

References to climate change, slavery, the detention of Japanese Americans during World War II, and conflicts with Native Americans have been removed from some national parks. Efforts are underway to ban some artwork, exhibitions and programs at the Smithsonian Institution dealing with race, slavery, immigration and sexuality.

This raises different questions than data collection. National parks and Smithsonian museums are federal property managed by the executive branch. The President has authority over what federal facilities display and how they present information to the public.

But there’s a difference between deciding what new content to create and removing existing content that presents historical facts. Japanese American internment happened. Slavery happened. Conflicts with Native Americans happened. Removing references to historical events doesn’t change the past – it just changes what the government officially acknowledges about the past.

Critics compare this to Orwell’s “1984” and the Ministry of Truth rewriting history. Supporters might argue the government shouldn’t be in the business of promoting particular narratives about controversial historical topics, and that removing politically charged content makes federal museums more neutral.

Both perspectives claim to support truth. They just disagree about whether presenting historical facts constitutes “promoting narratives” or whether removing those facts constitutes suppressing truth.

The Shutdown’s Compounding Effect

The government shutdown that began October 1 has suspended additional data collection: the monthly jobs report, agricultural data, health statistics, and scientific information regularly provided to the public. Some of this will resume when the shutdown ends. But some programs that were discontinued during the shutdown might never restart, particularly if they’re deemed “non-essential” under shutdown protocols.

This is where executive authority over shutdowns intersects with executive authority over data collection. When agencies make decisions about what’s “essential” during a shutdown, they’re making value judgments about what information is important enough to continue collecting even without appropriations.

The fact that the BLS inflation team was initially furloughed – potentially leaving Social Security recipients without COLA information – suggests the administration’s initial judgment was that even politically sensitive economic data wasn’t “essential.” The quick reversal after recognizing the political consequences suggests the decision was corrected, but it raises questions about what other data might be quietly discontinued during the shutdown.

What the Founders Would Say

The Founders didn’t anticipate the modern administrative state with its vast data collection apparatus. They created a Constitution for a small federal government that mostly collected customs revenues and ran a post office.

But they did care deeply about informed citizenship. Madison wrote that “knowledge will forever govern ignorance, and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” He understood that self-government requires citizens to have access to information.

Jefferson believed in maximum transparency for government operations. He’d likely argue that government-collected data should be public by default, not suppressed because it’s politically inconvenient.

Hamilton, more comfortable with executive power, might acknowledge the President’s authority to prioritize certain data collection over others based on policy goals. But even Hamilton believed executive power should be exercised openly and with accountability.

None of them would recognize a world where the federal government collects vast amounts of data about every aspect of American life – from air quality to emergency room visits to labor market trends. But they’d probably all agree that whatever data the government does collect should be available to citizens who need it to hold government accountable.

The “1984” Comparison

Critics invoking Orwell’s “1984” and the Ministry of Truth are making a serious accusation: that the Trump administration is systematically rewriting reality by eliminating data that contradicts its preferred narrative.

The comparison has some validity. When governments stop collecting data about problems they don’t want to acknowledge, they’re not solving those problems – they’re just making them invisible. If we stop tracking food insecurity, hungry Americans don’t disappear. If we stop measuring greenhouse gas emissions, climate change doesn’t stop. If we stop recording police misconduct, it still happens.

“Bad news or withholding information on what is occurring in our society doesn’t change by not knowing it.” – Max Stier, Partnership for Public Service

But the “1984” comparison can be overwrought. Orwell’s dystopia involved totalitarian control of all information. The Trump administration is exercising executive authority over federal data collection – authority that exists within the constitutional system. Private researchers, state governments, universities, and non-profits can still collect data the federal government has stopped gathering. The information doesn’t disappear into “memory holes” – it just stops being officially collected at the federal level.

That’s still concerning if you believe federal data collection serves important public purposes. But it’s different from totalitarian information control.

The Policy Consequences

The practical consequence of eliminating data collection is that policymakers make decisions with less information. If Congress cuts food stamps without tracking food insecurity, they won’t know if the cuts are causing increased hunger. If EPA eliminates pollution reporting requirements, regulators can’t measure whether environmental policies are working. If CDC stops tracking injury data, public health officials can’t identify emerging safety problems.

This could be intentional – reducing data collection makes it harder to prove policies aren’t working. Or it could be ideological – believing that government shouldn’t be measuring these things because the measurements themselves justify government intervention.

Either way, the result is that evidence-based policymaking becomes harder. Debates become more ideological and less empirical when nobody can point to reliable data about what’s actually happening.

The Congressional Authority Question

Congress has authority to require specific data collection through legislation. If Congress believes certain information is important enough, they can pass laws mandating that agencies collect and publish it. The fact that they haven’t done this for many programs suggests Congress has been content letting the executive branch decide what data to gather.

But Congress also appropriates money with the expectation that agencies will use it for certain purposes. If Congress appropriates funds for EPA to monitor pollution, and EPA stops monitoring pollution, that’s potentially misusing appropriated funds.

This is where the constitutional separation of powers gets tested. Congress controls the purse, but the President controls execution. When the President stops agencies from performing functions Congress expected them to perform, who wins?

Usually, this gets resolved through appropriations fights rather than constitutional litigation. Congress can condition funding on specific data collection requirements. The President can veto appropriations bills that contain requirements he opposes. The system forces negotiation and compromise.

But during a shutdown when there are no appropriations at all, the President has maximum discretion over what happens with federal programs – including data collection.

The Constitutional Reality

The Constitution gives the President broad authority over the executive branch, including federal agencies that collect data. Absent specific statutory requirements, the President can decide what information agencies gather and publish. That’s a feature of executive power, not a bug.

Whether that authority is being used wisely is a political question, not a constitutional one. Critics who invoke “1984” are arguing the administration is making bad decisions that harm the public interest. But bad decisions aren’t unconstitutional – they’re just bad.

The remedy for an administration that suppresses data is political: vote for different leaders who will restore data collection programs. Congress can also act by passing laws requiring specific data collection and making appropriations conditional on maintaining certain programs.

What citizens don’t have is a constitutional right to government-collected data. The First Amendment protects citizens’ right to gather and publish their own information, but it doesn’t require the government to collect data on citizens’ behalf.

That’s the uncomfortable constitutional reality: the President probably has authority to do most of what critics are calling “Orwellian.” The question is whether the political system will hold him accountable for using that authority in ways many people believe harm the public interest.

In our constitutional system, that accountability comes through elections, congressional oversight, and public pressure – not through courts declaring that citizens have a right to BLS employment reports or EPA pollution data. The system assumes an informed public will demand the information they need. Whether that assumption still holds in 2025 is being tested right now.