Kilmar Abrego Garcia just lost his latest bid to stay in America, but his story is far from over. An immigration judge in Baltimore denied his application to reopen his 2019 asylum case on Wednesday, setting up yet another round in what’s become one of the most legally bizarre immigration sagas in recent memory.

This is the Salvadoran man who was wrongfully deported to El Salvador in March, brought back to the U.S. by Supreme Court order in June, immediately charged with human smuggling, and is now facing deportation to Uganda – a country he’s never been to and has no connection with whatsoever.

His case has become a flashpoint in the immigration debate, but underneath all the politics lies a genuinely strange constitutional question: can the executive branch just ship people to random countries as punishment for challenging deportation orders?

At a Glance

- Immigration judge denied Abrego Garcia’s motion to reopen his 2019 asylum case, but he has 30 days to appeal

- Abrego Garcia entered the U.S. illegally as a teenager, has an American wife and children, and has lived in Maryland for years

- He was wrongfully deported to El Salvador in March, brought back by Supreme Court order, then charged with human smuggling

- ICE now wants to deport him to Uganda or Eswatini – countries with which he has no connection

- At stake: whether the executive branch can use deportation to third countries as retaliation for legal challenges

The Immigration Odyssey Nobody Could Make Up

Abrego Garcia’s story is complicated enough that it’s worth laying out the timeline, because each twist raises different constitutional questions.

He came to the U.S. illegally as a teenager from El Salvador. In 2019, immigration agents arrested him. He requested asylum but wasn’t eligible because he’d been in the country for more than a year – there’s a one-year filing deadline for asylum applications. However, the immigration judge ruled he couldn’t be deported to El Salvador because he faced danger from a gang that had targeted his family.

That left him in legal limbo – he couldn’t get asylum, but he also couldn’t be deported to his home country. He stayed in the U.S., got married to an American citizen, had children who are U.S. citizens, and lived in Maryland.

Then in March 2025, ICE mistakenly deported him to El Salvador anyway. He ended up in a notorious Salvadoran prison. His case became a rallying cry for immigration advocates who saw it as proof that Trump’s deportation machine was out of control, sending people to countries where judges had already found they’d face danger.

The Supreme Court eventually forced the Trump administration to bring Abrego Garcia back to the U.S. But instead of correcting the error, the administration immediately charged him with human smuggling based on a 2022 traffic stop in Tennessee.

Now ICE wants to deport him to Uganda. When his lawyers objected, ICE offered Eswatini as an alternative. These aren’t countries where Abrego Garcia has ever lived, has family, speaks the language, or has any connection whatsoever. They’re just countries that apparently have agreements with the U.S. to accept deportees from third countries.

His attorneys argue this is retaliation – punishment for standing up to the administration and becoming a public symbol of wrongful deportation.

The Constitutional Question Nobody Wants to Ask

Here’s what makes this case constitutionally fascinating rather than just politically charged: the executive branch appears to be using deportation to a random third country as a form of punishment.

The Constitution gives Congress broad authority over immigration through the Naturalization Clause. Congress has passed detailed statutes about who can be deported and under what circumstances. Those statutes generally assume people will be deported to their country of origin – the place they came from and presumably still have ties to.

But what happens when the executive branch can’t deport someone to their home country because a judge found they’d face danger there? Can the executive just pick any random country willing to take them?

The Immigration and Nationality Act does allow deportation to alternative countries in certain circumstances. But it’s supposed to be based on factors like where the person was born, where they hold citizenship, or where they have family connections. The statute doesn’t authorize “we’ll send you wherever we can find a country willing to take you as punishment for challenging your deportation.”

If the executive branch can deport people to random countries they have no connection to, that’s not immigration enforcement – it’s exile. And the Constitution has something to say about using the government’s power as punishment.

The Due Process Problem

The Fifth Amendment says no person shall be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” That word “person” is important – it doesn’t say “citizen.” The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that non-citizens in the United States are entitled to due process protections.

Abrego Garcia got due process in his original deportation proceedings. The immigration judge found he couldn’t be sent to El Salvador because of the danger he’d face there. That’s the process working correctly – the judge evaluated his claim and made a decision based on law and facts.

But then ICE deported him to El Salvador anyway, in direct violation of that judicial order. When the Supreme Court forced them to bring him back, instead of saying “we made a mistake,” the administration charged him with crimes and decided to deport him to a completely different country that was never part of the original proceedings.

That looks a lot like the executive branch ignoring judicial decisions it doesn’t like and finding creative ways to achieve the same result – deportation – through different means. If that’s what’s happening, it’s a due process violation and a separation of powers problem.

Immigration judges are part of the executive branch, not the judiciary. They work for the Department of Justice. But their decisions are supposed to be independent and binding. When ICE can simply ignore an immigration judge’s ruling and do what it wants anyway, the entire system of immigration courts becomes meaningless.

The Human Smuggling Charges

The Trump administration’s human smuggling charges against Abrego Garcia are based on a 2022 traffic stop in Tennessee. That was three years before he became a public figure in the deportation debate. But the charges weren’t filed until June 2025, immediately after he was brought back to the U.S. following the wrongful deportation.

The timing is suspicious enough that Abrego Garcia’s attorneys argue it’s retaliatory prosecution – the government charging him with crimes not because the evidence newly came to light, but because he embarrassed the administration by becoming a symbol of deportation gone wrong.

Retaliatory prosecution is unconstitutional. The government can’t charge you with crimes as punishment for exercising your legal rights or criticizing the government. But proving retaliation is difficult. The government can always point to the underlying conduct and say “we’re prosecuting him because he committed crimes, not because he challenged us in court.”

The constitutional question is whether a three-year gap between the alleged crime and the charges, combined with the charges being filed immediately after a Supreme Court rebuke, is enough to prove retaliatory intent.

If Abrego Garcia is convicted of human smuggling, it would eliminate any remaining legal obstacles to his deportation. That makes the criminal case look even more like a tool to achieve an immigration outcome that courts have already questioned.

The Third-Country Deportation Question

Here’s where immigration law gets truly bizarre. The U.S. has agreements with certain countries to accept deportees who can’t be returned to their home countries. These agreements are supposed to be used when someone is stateless or when their home country won’t take them back.

Uganda is one of those countries. So is Eswatini. Neither has any connection to Abrego Garcia beyond the fact that they’ve agreed to accept third-country deportees in exchange for U.S. foreign aid and diplomatic benefits.

Deportation to a third country isn’t supposed to be punitive. It’s supposed to be a practical solution when someone needs to be removed from the U.S. but can’t go home. But when ICE proposes sending someone to Uganda or Eswatini – countries where they don’t speak the language, have no family or support network, and have never been – it’s hard to see it as anything other than punishment.

The statute allows alternative country deportations, but it doesn’t clearly authorize using them as retaliation. And if the purpose is punishment rather than immigration enforcement, that raises Eighth Amendment questions about cruel and unusual punishment.

Abrego Garcia’s case tests whether there are any limits on the executive branch’s discretion to choose deportation destinations. Can they send anyone anywhere as long as they can find a country willing to accept them? Or does the Constitution require some rational connection between the person and the destination country?

The 30-Day Appeal Window

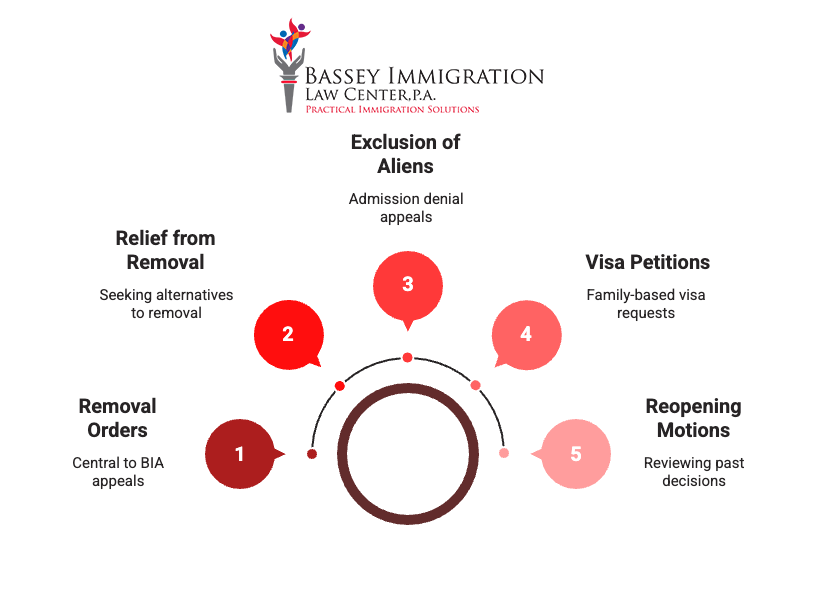

Wednesday’s ruling from the Baltimore immigration judge means Abrego Garcia has 30 days to appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals. That board is also part of the Department of Justice, also within the executive branch. It’s not an independent court.

If the BIA denies his appeal, he can seek review in federal district court. That’s where he’d finally get before Article III judges with life tenure and independence from the executive branch. But by that point, ICE might have already deported him to Uganda or Eswatini.

Once someone is physically removed from the United States, federal courts lose most of their ability to provide relief. You can’t undo a deportation by court order if the person is already in another country.

That’s why Abrego Garcia’s lawyers have been filing emergency motions trying to block deportation while appeals proceed. And that’s why the Trump administration has been trying to deport him quickly before courts can intervene.

It’s a race between executive action and judicial review – and the Constitution doesn’t clearly say who should win that race.

The Bigger Picture on Executive Power

Abrego Garcia’s case is about more than one man’s deportation. It’s a test of how much discretion the executive branch has in immigration enforcement and whether courts can effectively check that discretion.

If the administration can wrongfully deport someone, get reversed by the Supreme Court, and then immediately charge them with crimes and propose deportation to a random third country – all without serious consequences – then executive power in immigration is essentially unlimited.

Congress passed detailed immigration statutes precisely to limit that kind of arbitrary executive action. Those statutes create procedures, require findings, and give people rights to appeal. But if the executive can ignore inconvenient rulings and find alternative ways to achieve the same result, the statutes become meaningless.

The Framers created a system of separated powers where courts could check executive overreach. But immigration law exists in a strange constitutional space where courts have traditionally given the executive enormous deference. The Supreme Court has said repeatedly that Congress has “plenary power” over immigration, and by extension, so does the President in executing immigration laws.

Abrego Garcia’s case tests the outer limits of that deference. At what point does executive discretion in immigration become executive lawlessness?

The Constitutional Reality

As Abrego Garcia’s legal team prepares their appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals, the constitutional stakes are clear: either immigration law means something – with procedures that matter and judicial findings that must be respected – or it’s just a fig leaf for unlimited executive discretion.

The Trump administration argues they’re following the law. Abrego Garcia entered illegally, missed the asylum filing deadline, and has been charged with human smuggling. They say deportation to a third country is authorized by statute and is a legitimate enforcement action, not retaliation.

Abrego Garcia’s lawyers argue the administration is using legal tools as weapons – selectively prosecuting him for old conduct, ignoring judicial findings about where he can safely be deported, and threatening to send him to countries with no connection to him as punishment for challenging the original wrongful deportation.

Both sides can point to statutes and precedents. But the real question is whether our constitutional system allows the executive branch to use immigration enforcement this way – as a tool to punish people who successfully challenge government action in court.

In 30 days, we’ll find out if the Board of Immigration Appeals thinks there’s any constitutional problem with deporting someone to Uganda just because you can. And eventually, if this case reaches federal court, we might finally get a clear answer about whether the separation of powers means anything in immigration law.

Until then, Abrego Garcia waits – an American family’s husband and father, facing exile to a country he’s never seen, for the crime of winning a Supreme Court case.