The Supreme Court just agreed to answer a question that’s never been asked in the 112-year history of the Federal Reserve: can a president fire a Fed governor?

The answer will determine whether the central bank that controls interest rates, inflation, and essentially the value of every dollar in your wallet operates independently of political pressure – or whether it becomes another tool in the President’s toolkit.

On Wednesday, the justices delivered a short-term blow to Trump by allowing Fed Governor Lisa Cook to keep her job until oral arguments in January. But the real constitutional drama is just beginning, and it goes far deeper than one economist’s mortgage paperwork.

At a Glance:

- The Supreme Court will hear arguments in January on whether Trump can fire Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook

- Cook remains on the Fed board until the case is decided – a rare recent loss for Trump on emergency stay requests

- Trump is the first president in Fed history to attempt removing a sitting governor

- At stake: whether “for cause” protections shield Fed officials from presidential control

- The case threatens to overturn or reshape Humphrey’s Executor, the 90-year-old precedent protecting independent agencies

The Constitutional Earthquake Nobody Saw Coming

Here’s what makes this case constitutionally explosive: it’s not really about Lisa Cook’s mortgage applications. It’s about whether the President has virtually unlimited power to fire officials in independent agencies – agencies that were specifically designed to operate free from political interference.

Trump moved to fire Cook in late August, citing allegations of mortgage fraud raised by housing finance agency chief Bill Pulte, claiming Cook listed two properties as her primary residence in mortgage documents signed before her 2022 Fed appointment. Cook denies any wrongdoing. But even if the allegations were true, the constitutional question remains: does that meet the “for cause” standard required by the Federal Reserve Act?

The Federal Reserve Act says governors can only be removed “for cause” – a deliberately vague term that courts have interpreted to mean serious misconduct or dereliction of duty, not mere policy disagreements. The law was written this way precisely to prevent presidents from firing Fed officials because they disagree with interest rate decisions.

For 90 years, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935) has stood as precedent protecting “bipartisan administrative bodies carrying out expertise-based functions with a measure of independence from presidential control.” That case established that Congress can create independent agencies with officials who serve fixed terms and can only be fired for cause – not at the President’s whim.

Trump’s legal team is essentially asking the Supreme Court to overturn or drastically narrow Humphrey’s Executor. And that would reshape the entire structure of the administrative state.

“Put simply, the president may reasonably determine that interest rates paid by the American people should not be set by a governor who appears to have lied about facts material to the interest rates she secured for herself.” – Solicitor General D. John Sauer

The Unitary Executive Theory Meets Economic Reality

Here’s the constitutional theory driving Trump’s argument: Article II vests “the executive Power” in the President. The unitary executive theory holds that this means the President must have complete control over everyone exercising executive power – including the power to fire them at will.

Conservative legal scholars have long argued that Humphrey’s Executor was wrongly decided, that it violates the separation of powers by creating a “headless fourth branch” of government that’s neither fully executive, legislative, nor judicial. They say if someone is exercising executive power (like enforcing regulations or managing the economy), they must answer to the President, who is accountable to voters.

But here’s where that theory crashes into economic reality: the Federal Reserve is not a typical executive agency. It’s a “quasi-private entity” with a unique structure deliberately modeled on the First and Second Banks of the United States that the Founders created.

Its independence from political pressure is what gives monetary policy credibility.

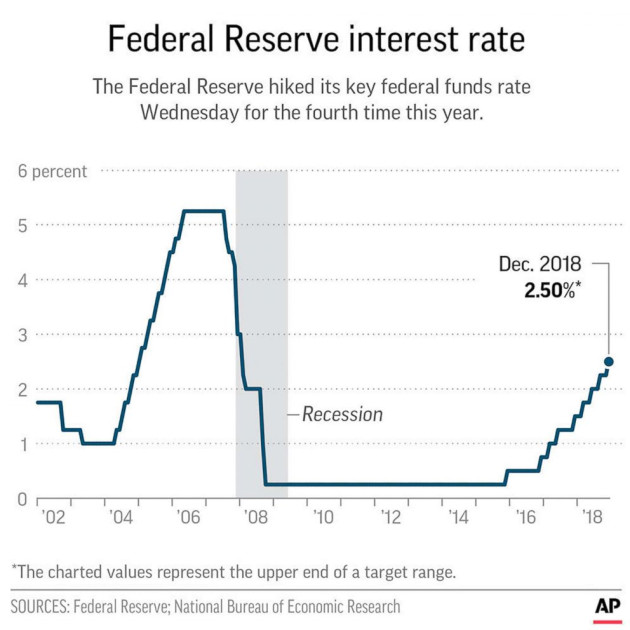

When the Fed raises interest rates to fight inflation, it’s often politically unpopular. Presidents always want lower rates, especially before elections. If the President could fire Fed governors who vote for rate increases, the central bank would become a political tool – and global financial markets would lose confidence in the dollar.

Former Fed chairs and Treasury secretaries from both parties filed briefs urging the Court to block Trump’s firing attempt, warning that Fed independence is essential to economic stability.

What “For Cause” Actually Means

The Trump administration argues that alleged mortgage fraud – claiming two homes as primary residences to get better loan terms – constitutes “cause” for removal under the Federal Reserve Act. Cook’s lawyers argue that even if the allegations were true (which she denies), conduct that occurred before her appointment to the Fed cannot be grounds for removal once she’s serving.

This gets to a fundamental question: what does “for cause” mean? The statute doesn’t define it. Courts have generally interpreted it to mean serious misconduct in office – things like accepting bribes, refusing to show up for work, or deliberately violating the law while serving. Pre-appointment conduct typically doesn’t qualify unless it directly bears on current fitness to serve.

U.S. District Judge Jia Cobb issued a preliminary injunction blocking Trump from firing Cook, ruling that Trump had failed to satisfy the stringent requirements needed to remove a sitting Fed governor “for cause” and that Cook could not be removed for conduct that occurred prior to her appointment.

The D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals agreed 2-1. Now the Supreme Court will decide – and the stakes extend far beyond one Fed governor’s job.

The Broader Constitutional Battle

Here’s what makes this case a potential game-changer: the Supreme Court has been steadily chipping away at independent agency protections. In Seila Law v. CFPB (2020), the Court struck down “for cause” protections for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s single director. In recent emergency orders, the Court has allowed Trump to provisionally fire members of the National Labor Relations Board and Merit Systems Protection Board.

But even in those cases, the Court explicitly noted that the Federal Reserve is different – it’s a “uniquely structured, quasi-private entity that follows in the distinct historical tradition” of banks the Founders themselves created.

The justices seemed to suggest Fed independence deserves special constitutional protection.

So when the Court agreed Wednesday to hear Trump’s appeal but kept Cook in her job until January arguments, that was significant. The Court has “overwhelmingly sided with Trump on emergency stay requests” in recent months. This rare loss suggests at least some justices have serious doubts about Trump’s authority here.

Trump’s lawyers argue that the Fed’s “uniquely important role” in the economy makes it even more critical that the President control who serves. Cook’s lawyers argue the opposite – that unique importance is exactly why Fed officials must be insulated from political pressure.

“We look forward to ultimate victory after presenting our oral arguments before the Supreme Court in January.” – White House spokesman Kush Desai

The Separation of Powers Tightrope

This case forces the Supreme Court to navigate treacherous constitutional territory. On one hand, the Constitution does vest executive power in the President. The Take Care Clause requires that he “shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” It’s hard to do that if you can’t fire subordinates who aren’t executing laws faithfully.

On the other hand, Congress has constitutional authority to create federal offices and set the terms under which officials serve. When Congress created the Federal Reserve, it deliberately included “for cause” protections to ensure monetary policy wouldn’t become a political football. That was Congress exercising its legislative power – and the Constitution doesn’t clearly say the President can override those statutory protections.

The Framers designed a system of separated powers with checks and balances. They didn’t want any branch to have unchecked authority.

An independent Fed, insulated from presidential firing threats, serves as a check on executive power over the economy. But a President unable to remove officials implementing policies he believes are harmful can’t effectively execute the laws or be held accountable by voters.

There’s no clean constitutional answer. Both sides have legitimate arguments grounded in different constitutional values.

What the Founders Would Say

Hamilton, who championed the First Bank of the United States, understood the value of central banking independence. He’d probably argue that some degree of insulation from political pressure is necessary for effective monetary policy – but he’d also insist on strong executive authority.

Madison would likely worry about creating too much unaccountable power in any institution, whether the presidency or an independent agency. He designed a system where ambition counteracts ambition, and power is divided to prevent tyranny.

Jefferson opposed the First Bank entirely, viewing it as unconstitutional federal overreach. He’d probably say the whole modern Federal Reserve system goes beyond constitutional authority, making the firing question moot.

But here’s what’s clear: the Founders never imagined the modern administrative state with hundreds of thousands of federal employees in dozens of independent agencies. They created a framework, not a detailed blueprint for every institutional question we’d face 250 years later.

The Stakes for American Governance

The Supreme Court’s decision will ripple far beyond Lisa Cook or the Federal Reserve. If the Court sides with Trump and allows at-will firing of Fed governors, it could signal the end of Humphrey’s Executor and independent agency protections across the government.

That would mean the President could fire the commissioners of the Securities and Exchange Commission, Federal Trade Commission, Federal Communications Commission, and dozens of other agencies designed to operate independently. Every regulatory decision would become subject to direct presidential control – and political pressure.

Supporters of the unitary executive theory say that’s good – it creates clear democratic accountability. If you don’t like how agencies regulate, vote for a different president.

Critics warn it would politicize expertise-based functions, turning economic policy, securities regulation, and even scientific research into political spoils. And it would concentrate enormous power in the presidency – exactly what the separation of powers is supposed to prevent.

The Constitutional Reckoning

As oral arguments approach in January, both sides will present competing visions of executive power and constitutional structure. Trump’s team will argue that the Constitution demands presidential control over all executive officials. Cook’s team will argue that Congress has constitutional authority to create independent institutions insulated from political interference.

The Court’s conservative majority has shown skepticism toward the administrative state and sympathy for expanding presidential power. But even this Court has recognized that Fed independence deserves special consideration. The case will be heard alongside a related dispute over Trump’s effort to remove Federal Trade Commission member Rebecca Slaughter in December, potentially signaling how the Court views independent agencies more broadly.

Here’s the fundamental constitutional question: In our system of separated powers, who controls the controllers?

Can Congress create officials who regulate the economy, enforce securities laws, and set interest rates without answering to the President? Or does the Constitution require that all executive power ultimately flow through – and be controllable by – the President?

The answer will determine not just whether Lisa Cook keeps her job, but whether the next economic crisis is managed by independent experts or political appointees looking over their shoulders at the Oval Office.

In a system designed for checks and balances, sometimes the most important check is the one that prevents any single person – even the President – from controlling everything.