A Green Light From the Court, But a Crossroads for Due Process

This week, the Supreme Court gave the Trump administration a procedural victory in its ongoing battle to reshape immigration enforcement.

In a 6-3 decision, the justices paused a lower court’s order, allowing the administration to resume deporting certain migrants to countries other than their homelands without the advance notice that a federal judge had required.

The ruling is a near-term win for a White House determined to accelerate deportations.

But it’s also a critical flashpoint in a much larger, more fundamental debate. This isn’t just about the logistics of removal orders; it’s about the reach of executive power and a recurring constitutional question:

What does “due process” truly mean for individuals, regardless of citizenship, when they stand on U.S. soil?

So what are we really looking at here – a necessary tool for national security, or a shortcut around one of the Constitution’s most basic guardrails?

A “Stay” Isn’t a Final Verdict

First, it’s important to understand what the Supreme Court did and did not do. The justices issued a “stay,” which essentially freezes a lower court’s command while the full legal case proceeds.

They did not rule on the ultimate legality of the administration’s “third-country deportation” policy.

Here’s the context: A group of migrants filed a class-action lawsuit after the administration sought to deport them to countries they weren’t from—in some cases, to nations like South Sudan, a country destabilized by years of conflict. This happens when a person’s country of origin refuses to accept them.

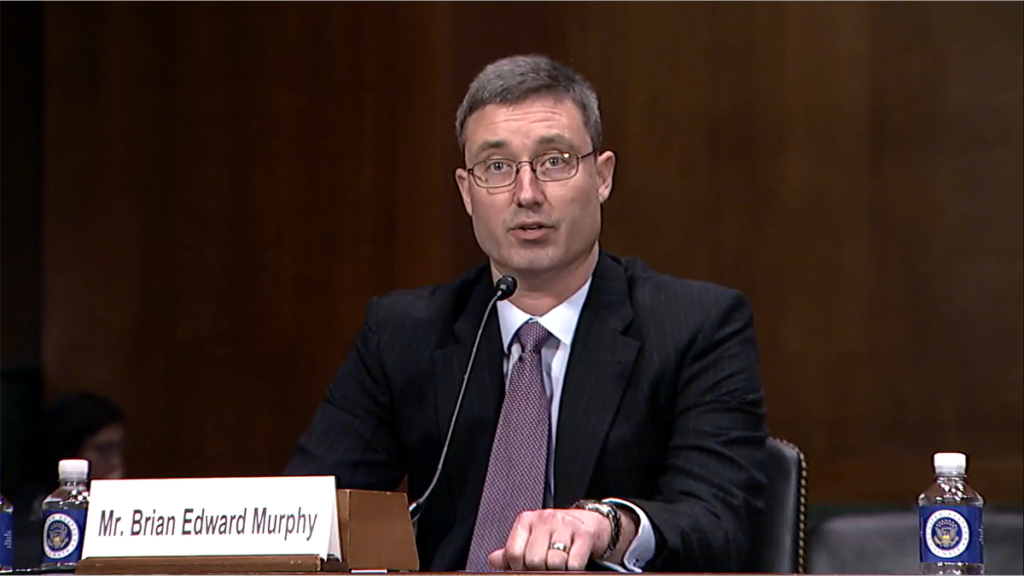

U.S. District Judge Brian Murphy in Boston intervened, ruling that these deportations could not proceed without giving the individuals proper written notice and a “meaningful opportunity” to argue their case—specifically, through a “reasonable fear interview” to assess whether they would face torture or persecution in that third country.

The Trump administration appealed, arguing Judge Murphy’s order was blocking them from removing “some of the worst of the worst illegal aliens.”

On Monday, the Supreme Court’s majority agreed to put that order on hold, allowing the deportations to continue for now.

The Constitutional Collision: Enforcement vs. Due Process

This case brings two powerful forces into direct conflict.

On one side is executive authority. The administration argues that it needs flexibility and speed to manage immigration and that court-ordered delays disrupt sensitive diplomatic agreements with the few countries willing to accept these individuals.

This position frames immigration enforcement as a core function of the executive branch, essential for national sovereignty.

On the other side is the Fifth Amendment. This is where the constitutional red flag appears.

The Fifth Amendment states that “No person shall be… deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

The key word is “person,” not “citizen.”

For over a century, the courts have interpreted this to mean that everyone physically within the United States is entitled to some level of due process. Judge Murphy and the migrants’ lawyers argue that deporting someone to a potentially dangerous country without a chance to even raise an objection is a profound deprivation of liberty without that due process.

The dissenting justices, led by a fiery opinion from Justice Sonia Sotomayor, saw the majority’s decision not just as a mistake, but as a dangerous abuse of the Court’s power.

She argued the government has shown it feels “unconstrained by law,” and that by granting this emergency relief, the Court was enabling “so gross an abuse” of its discretion, exposing people to the risk of torture or death without a proper hearing.

A War of Attrition Over Power

This ruling doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It is a single battle in a wider conflict between the Trump administration’s immigration agenda and the judiciary. Since the start of the president’s second term, his administration has moved aggressively to test the boundaries of its authority, rolling back asylum processes, ending humanitarian parole programs, and clashing with what White House officials have repeatedly called “activist” judges.

The Supreme Court’s decision to intervene on an emergency basis—part of what has become known as its “shadow docket”—is itself a point of contention.

These fast-tracked rulings come without the extensive briefing and public oral arguments of a regular case, leaving lower courts and the public with little reasoning to follow. Critics argue this practice allows the Court to make monumental policy changes without full transparency or deliberation.

The Bottom Line

The Supreme Court has given the administration the green light to proceed, but the fundamental legal and moral questions remain unresolved. The case will continue to work its way through the appeal process and may very well land before the justices again for a final ruling on the merits.

This debate forces a national reckoning. Do we prioritize swift enforcement, even if it means eroding procedural safeguards that have long been a hallmark of American justice? Or do we insist that the constitutional promise of due process, however inconvenient for enforcement, applies to every person the government seeks to expel?

The answer will define not only the limits of presidential power but also the character of the nation.